Voices uncensored: 'Indigenous Screen' brings suppressed stories to light

"We are going to display cinema made about our lives."

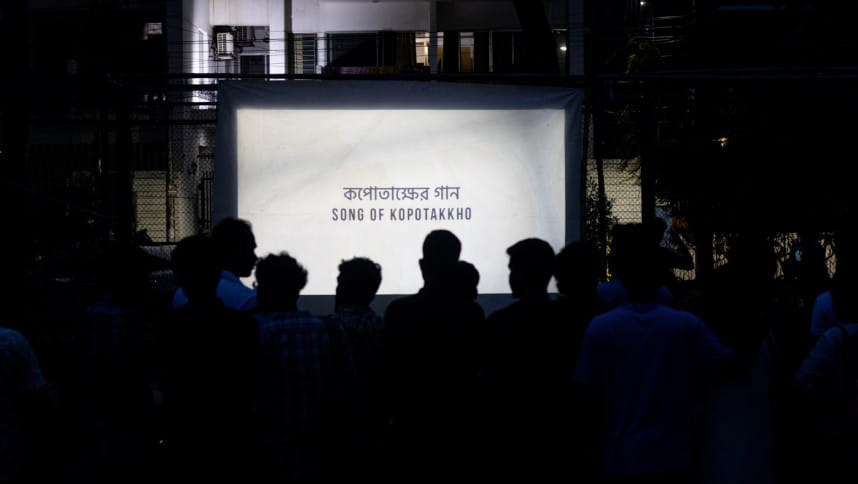

No big speeches, no dramatic reveals- the hosts of "Indigenous Screen" wished a steadily increasing crowd, a hearty evening and just the aforesaid one-liner as the films made by indigenous filmmakers began to roll out one after another. Yesterday, on the first day of the two-day event "Indigenous Screen", five films were screened under the evening sky at the Lalmatia D Block field, an initiative organised by the Indigenous Artists' Unity.

You may not recognise these films from any posters. These are films that were not only challenging to create but even more difficult to release. Some have almost no online presence, while one was banned for nine years. Considering the censorship board prohibits commercial release in its home country without its approval, most of these films have been screened in international festivals garnering praise in plenty.

"Indigenous Screen" hence brings forward suppressed films about suppressed communities voicing their lifestyles and struggles. The first day featured films like "Khumi I Awmnai Rita" (2006), "Coal-milk" (2007), "Song of Kapotakkho" (2021), "A'bima" (2021), and "Mor Thengari" (My Bicycle) (2015).

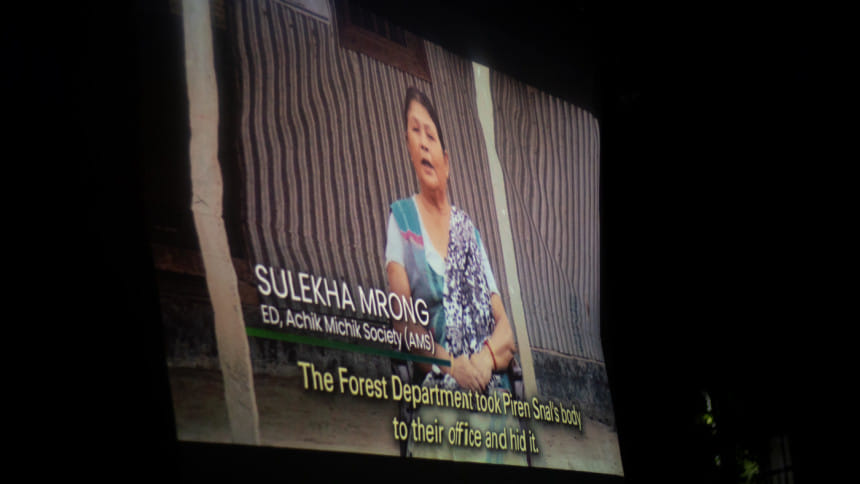

Featuring different indigenous communities across the country, the films explore different areas yet are all united by a common message of seeking recognition and fighting for survival. "Song of Kapotakkho" (2021) directed by Subrota Kumar Munda is a short film about the Munda community and their lifestyle. The documentary film sings of their livelihood and the harsh realities of struggling to simply manage food each day. On the other hand, "A'bima" (2021) delves into the lives of the Garo and Koch communities, tracing their journey from being free people to being displaced by tourism projects. The documentary film depicts the effects of tourism-induced developmental projects that compelled the communities around Tangail to protest for survival—how national parks, firing ranges, and eco-park projects systematically attempted to restrict their freedom. The film pays tribute to Piren Snal, who was killed during one such protest, and Cholesh Ritchil, who was later assassinated in another.

A similar story of resistance is portrayed in Molla Sagor's "Coal-milk" or "Dudh-koyla" (2007). As the film began, "Hara koyla khuni chai na" chants filled the air. When the dwellers of Bucchigram, a village under Phulbari Upazila of Dinajpur, were asked to leave because a coal mine was going to be established, it posed a threat to their survival. A community that thrives on agriculture, dance, and harmony chants throughout the day in slogans against the coal-mining industry and for the right to live in their homes. Alternately, "Khumi I Awmnai Rita" (2006) by Shuvashis Chakma Ittukgula is a looking glass placed inside the culture and traditions of the Khumis, one of the smallest ethnic groups of Bangladesh. The documentary film intricately showcases jum cultivation, sacrificial rituals for good cultivation, and different kinds of ceremonies practised by the Khumi community.

The final film of last night was banned for nine years in Bangladesh—stuck in the censorship limbo. Aung Rakhine's "Mor Thengari" or "My Bicycle" is the first feature film of Bangladesh made entirely in the Chakma language that was never allowed to be released commercially. In the first few minutes of the film, the protagonist reminisces about how things once were as the boat carrying him and his bicycle rows through Kaptai Lake, the artificial lake created by the flooding from the Kaptai dam, which submerged the arable land of the Jummas in the 1960s. One can wonder about the extent of amplified resistance in the film. Yet, "Mor Thengari", is at heart a tale about a man and his bicycle. In between its simplicity, the film touches on the gradual introduction and acceptance of modern technology in the remote village. But let it serve as a reminder that the 64-minute feature film was asked to be stripped of 25 minutes of its runtime for a censorship certificate. Now that the full, uncensored film is being freely screened, the audience can have the opportunity to analyse the reasons behind the bans.

One of the organisers from Indigenous Artists' Unity, Santua Tripura said, "Our rights have been repressed for long and so have been our art. We do not even receive any government funding for making films. In the wave of change, however, we are hopeful for things to get better. We want indigenous people and their films to be free."

The Indigenous Artists' Unity dedicates itself to taking an artistic approach to raise voices and let people know about indigenous communities and their rights. Besides the series of film screenings, the community has been engaged in making murals across the city and is planning further initiatives.

While protests are ongoing across CHT in response to the destruction of graffiti advocating indigenous rights and justice, the film screenings serve as a powerful form of resistance using filmography to assert the struggles and resilience of the indigenous population of the country.

An array of films await the audience for the second day of screening including "Life is Still Not Ours" (2014), "Kalpana…Not Imagination" (2016), "Felim: Cinema for Identity" (2017), and "Choto Pakhi" (2017). To catch uncensored versions of candid films by indigenous creators and be a part of the movement to free indigenous films and people, join the screenings scheduled today at House 12, Road 101, Gulshan 2.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments