Dhaka stares down the barrel of water

Once widely abundant, the freshwater for Dhaka dwellers continues to deplete at a dramatic rate and may disappear far below the ground.

With rivers and waterbodies around the city either polluted or encroached upon, almost 70 percent of the water needed for quenching the thirst of Dhaka's 23 million people and supplying to homes and industries comes from groundwater.

Dhaka Wasa (Water & Sewage Authority) alone every day pumps out about 3.3 million cubic metres (m3) of groundwater, a volume that can fill up at least 20 cricket stadiums the size of the one in Mirpur. Shockingly, Dhaka Wasa during supply wastes five stadiums' worth of this precious water in system loss every day.

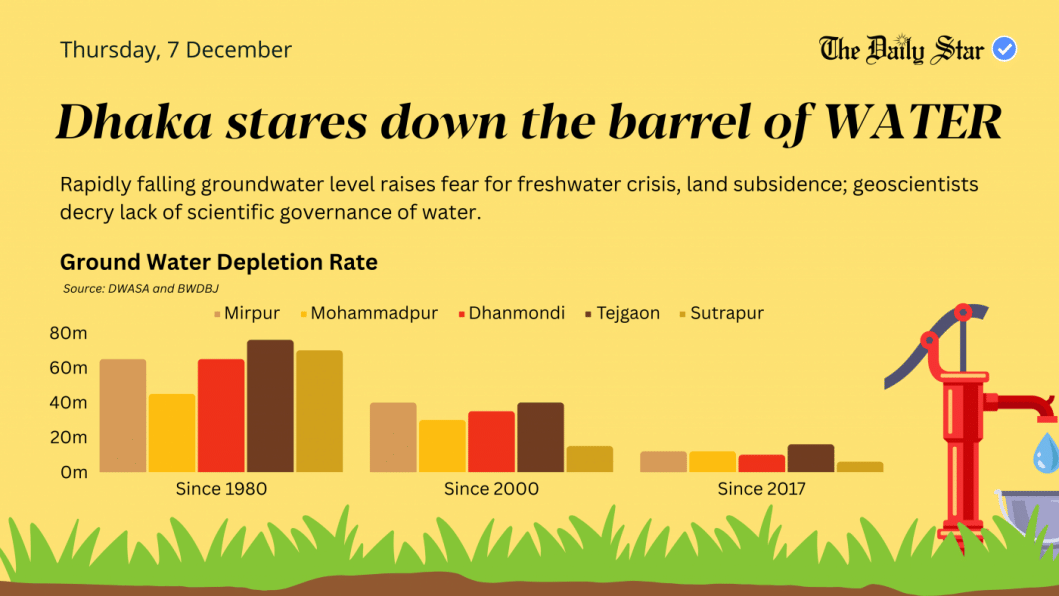

Reports of the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB), which has been monitoring water quantity and quality for 60 years through a network of 1,272 observation wells across the country, indicate a jaw-dropping fall of 2 metres (7ft) a year in the groundwater level of Dhaka.

A great disaster is taking shape under Dhaka

"We can't see it as it is happening underground. But we can make full sense of it looking at the historical data."

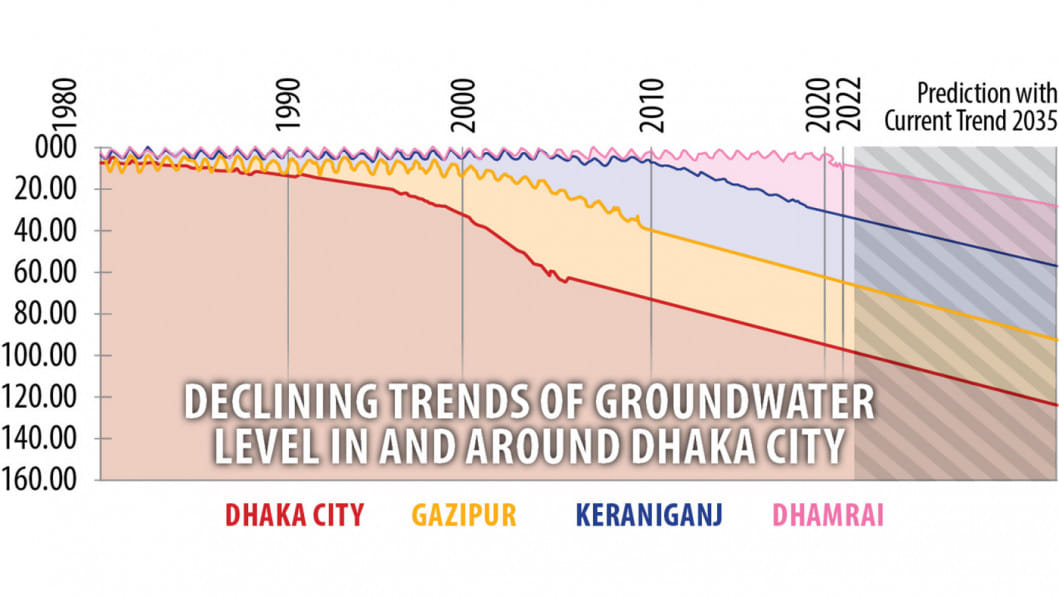

The drop rate of water level in Dhaka is eerily consistent with the forecasts made by the BWDB and researchers decades back: from 25 metres in 1996, it dropped down to 45 metres in 2005, 60 metres in 2010, and 75 metres in 2023.

In the year 2050, it is likely to fall to 120 metres, with the demand, as projected by Wasa, ever-spiralling: 3.5 million cubic metres in 2025, 4.3 million in 2030 and 5.2 million in 2035.

Apart from the 1,000 Wasa pumps, 2,000 private and thousands other unauthorised deep tubewells are whirring all the time to drain the groundwater and meet the growing demand of the world's third most densely populated city after Mogadishu in Somalia and Tanta in Egypt.

The demand for freshwater is rising exponentially as the capital is getting bigger and bigger to accommodate unplanned industrialisation and urbanisation on its outskirts. According to the leading statistics database Statista, Dhaka (30,911 people per square km) is even more densely populated than the Rohingya refugee camp in Kutupalong (28,958 persons per square km).

The impact of the uncontrolled overdraw from the groundwater reservoir, geologically known as an aquifer, is colossal and it is clearly reflected in the BWDB data. In the central parts of Dhaka, freshwater that could have been accessed at a depth of 6 metres (20ft) in 1970 has now gone down to 73 metres (240ft) and below in 2023. Geoscientists have identified a "compound cone of depression", which is a deep caving-in of sand layers due to the significant loss of stored water, extending nearly 100km from the city centre to surrounding upazilas -- Tongi, Savar, Dhamrai, Dohar, and Nawabganj. At the moment, under the central parts of Dhaka, the maximum dip in the water level of the upper aquifer is 73 metres (240ft), and the deeper aquifer, which is separated from the upper one by thick layers of clay and not sand, is 85 metres (278ft).

However, the unique sand layers of this largest delta in the world have stopped the cave-in from culminating in land subsidence. Thick sedimentary layers of the upper aquifer could absorb the pressure of water loss so far, with sand particles readjusting and resettling the structural change. But groundwater experts start to worry when the deep tubewells of Wasa and others bore through the clay layers to extract water from deeper aquifer beyond 300 metres (984ft).

Clay layers behave just the opposite to sand layers. A cone of depression in clay layers [which is up to 60ft thick] is most likely to lead to land subsidence and destruction of aquifers for good

If the current trend continues, a disaster some decades down the line may put a full stop to freshwater for Dhaka as well as raise the possibility for subsidence like Jakarta, which is regarded as the world's fastest sinking metropolis mainly due to uncontrolled exploitation of groundwater. One-third of the Indonesian capital is feared to be submerged by 2050 due to the continuous plundering of aquifers.

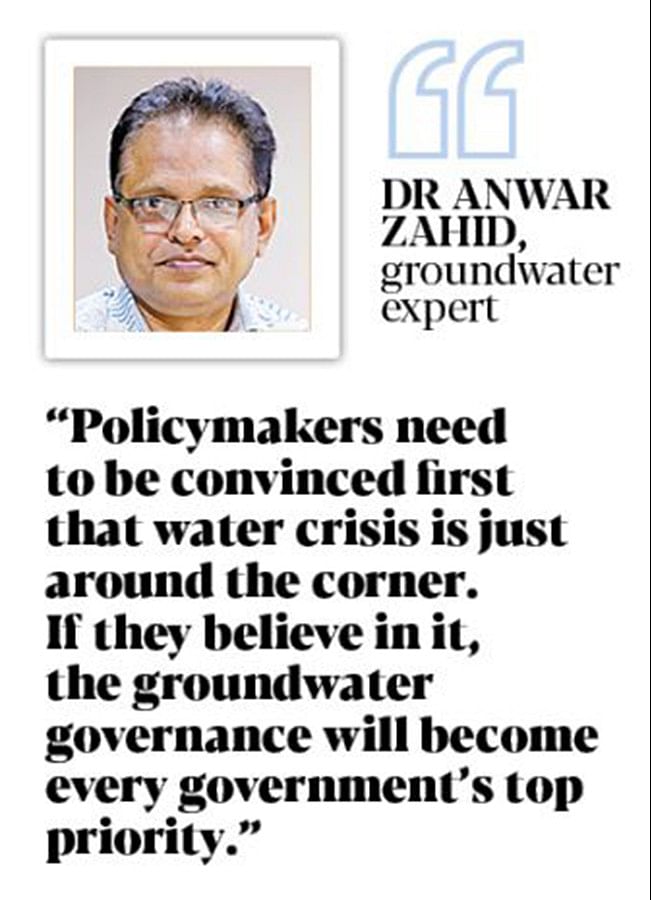

"You really can't take groundwater for granted. As a national priority, the government must manage aquifers and use water scientifically," added the internationally referred groundwater expert.

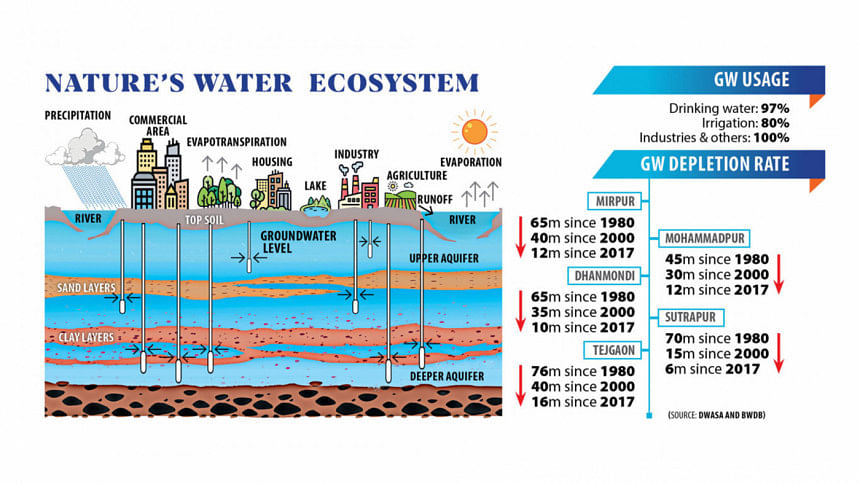

Groundwater is considered by geoscientists as nature's very special gift to the people in the Bengal basin, a vast sediment-filled region upon which lies Bangladesh and a part of West Bengal. The enormous underground reservoir for freshwater was crafted slowly over thousands of years by the Ganges and the Brahmaputra that brought in tonnes of silt and sediment every year from as far away as the Himalayas to form the delta's spongy soil. The entire ecosystem of nature works like a well-oiled machine: we pump water out and the porous soil quickly captures the rain-running-flood water before sending it down to the aquifer with filtration through layers of soil on the way. But, the mindless extraction of groundwater upsets the ecosystem to an incredible extent.

"The thumb rule for groundwater management is: the extraction should not be more than the amount recharged," insists Dr Anwar.

But there comes the challenge of resolving the time puzzle of withdrawal and recharge of groundwater: draining by humans takes seconds and refilling by nature ages. The concretisation of the capital city and the gradual extinction of waterbodies also appear as serious barriers to natural recharging of aquifers. Roughly, it takes at least 100 years for rainfall or floodwater of today to reach aquifers down to 100 metres (328ft) and thousand years beyond 300 metres (984ft), depending on the types of sediments that formed the groundwater reservoir.

Dhaka is in dire straits for sure. The impacts of climate change are also compounding the freshwater crisis. Rising sea level is a growing threat to sweetwater reserve. Yet, Dhaka can stay out of danger through scientific governance of groundwater, believes Dr Anwar.

"But for that, policymakers need to be convinced first that the water crisis is just around the corner. If they believe in it, groundwater governance will become every government's top priority," he said.

The government enacted the Water Act in 2013, formulated rules in 2018 and hardly enforced it until now. Then there are a lot of inadequacies in the act, which deals with all water resources, giving the least focus on groundwater that is being used and abused the most.

The law outlines water priority for sectoral use, budget for water-stressed areas, and conservation of water resources with Warpo (Water Resources Planning Organisation) at the helm for implementation. In reality, Warpo, led by a bureaucrat and not a geoscientist or engineer, is only involved in planning and not implementing.

The Warpo is not even designed to dictate terms of groundwater usage by multiple water authorities like Wasa, DPH (Department of Public Health), let alone that of private entities. As per the water priority provision for water-stressed areas, drinking water comes first and water for industry eighth. In that light, no industry should have been able to use groundwater without the permission of the Warpo.

The most critical issue is the governance of groundwater. Ideally, a fully empowered single authority under the water resources ministry should govern the endangered resources, argued Dr Anwar.

"A groundwater commission, led by geoscientists or groundwater experts, may save Dhaka from dying without water," he quipped.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments