Arsenic danger still not over

The government is not paying adequate attention to the health hazards caused by arsenic contamination even though millions of people are exposed to it, says Professor Abul Hussam, a US researcher of Bangladesh origin.

Even a decade ago, there were around 10 million tube wells and the number has certainly increased with the rise of population, he says.

But people are rarely talking about it these days, which does not mean the danger of arsenic contamination has disappeared, he tells The Daily Star in an exclusive interview.

Director of the Centre for Clean Water and Sustainable Technology (CCWST) in the department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at George Mason University, Virginia, USA, Hussam says, "Arsenic contamination in drinking water is very much there. At least 20 million people in this country are exposed to risks of this contamination.”

As long as people in this country drink tube well water, there will be arsenic problem and there is no simple method by which one can remove arsenic from the groundwater on a large scale, he observes.

Referring to a 2006 research which showed only 29 percent people switched to safe tube wells, he says 57 percent people in those areas are still exposed to arsenic as there is no clear indication that they have adopted safer methods for consuming drinking water.

Apart from arsenic, Professor Hussam informs, there is another neurotoxin called manganese, and other toxic trace metals, which could be found in tube well water.

"Unless we find alternative potable water, none of these toxic materials would go away from tube well water," he observes.

If the concentration of iron is high in any tube well, it is likely that the concentration of manganese, too, will be high even if there is no arsenic in the water, he says, adding studies on Bangladeshi children have clearly proved presence of manganese in tube well water.

The World Health Organisation has set 400 ppb (parts per billion) as a desirable quantity for manganese in drinking water. For arsenic it is 10 ppb.

“And this is an alarming situation for us,” says Hussam who won the Grainger Challenge Prize for Sustainability Gold Award by the National Academy of Engineering, USA in 2007.

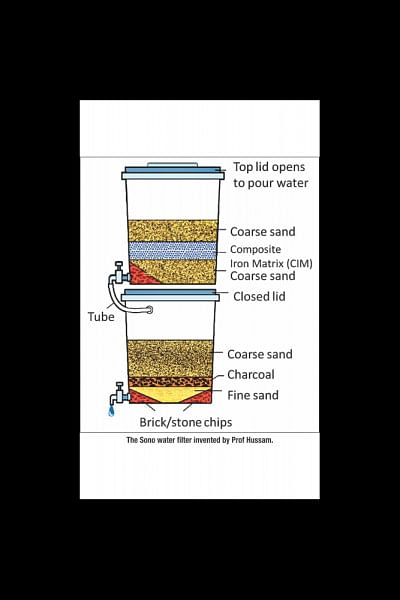

Professor Hussam -- who has invented a Sono water filter that can successfully make drinking water free from arsenic, manganese, and other toxic trace metals, bacteria and viruses -- believes no water is totally safe for drinking without filtration.

"The main point is, whether the water quality we get from tube wells is potable. And the answer is 'No'," he says.

In line with WHO guidelines, the government has set a standard for drinking water. "I think most tube wells in Bangladesh do not meet up the standards set by the government," he shares.

Professor Hussam cites a research report entitled "Failure of sanitary well to protect against cholera and other diarrhoeas in Bangladesh" conducted by Dr R Levine published in Lancet magazine in July 1976. Further studies in 2001 by a group of icddr,b scientists reaffirmed the conclusion -- "It has been generally believed in Bangladesh that ground water is relatively free from microorganisms and, therefore, fit for human consumption without treatment. However, the results of this study show clearly that all samples of tube well water in rural Bangladesh that were examined contained high counts of bacteria and zooplankton, as well as fungi."

“This means, we knew the tube well water was not totally safe from the very inception of tube well propagation in Bangladesh, whose number is more than 10 million and counting”, he said.

Asked about the reason behind the government's laxity over taking action regarding this, especially when they know the arsenic problem was there, Professor Hussam says the primary financing for arsenic research came in Bangladesh from donor agencies. In addition, local scientific expertise in the field was not developed and the government is not willing to spend money for arsenic mitigation as it is not an easy job to make sure people get safe drinking water, he explains.

“Actually the crisis is so massive in terms of number of people affected by it that it is very hard for the government to handle it without a plan. The government is not resourceful enough to address the problem but development partners could help solve this massive potable water problem,” he further explains.

“We need to remember one thing, even if the people know that the water of their tube well was contaminated by arsenic, they may drink the water because they may not have any other choice,” he says, adding “even sometime people may have access to safe tube wells, still they do not want to go and collect water from those tube wells.”

Asked what the government should do for the potable water sector, Hussam says the irony is that from the inception of this crisis most research work on drinking water quality of Bangladesh was conducted by foreign researchers. The country must develop its institutional capacity to deal with this crisis instead of depending on foreign money and expertise.

He recommends the government test all the tube wells in the country. An awareness campaign and a long-term plan to develop surface water as potable source are also necessary. He reiterates that water filtration either at the sink or at the source must not be avoided.

Professor Hussam has been working to further improve his Sono filter. About 280,000 Sono filters are used in Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and India to produce potable water for millions. Now he and some of his students are developing inline Sono filters to enhance the filter capacity.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments