Default loans soar

Default loans have dogged the country's banking sector for nearly three decades now, despite various reform efforts, in an alarming pattern that has damaged the economy and deprived honest borrowers of funds.

As of June, defaults amounted to Tk 63,365 crore, which is 10.06 percent of the total outstanding loans, according to the latest data from Bangladesh Bank.

If the written-off and rescheduled loans are taken into account, the sum would easily cross the Tk 100,000 crore-mark.

Thanks to the growing default culture, banks are losing out on revenues: they have to make provisioning against the bad loans from their incomes.

And the situation is particularly dire at state banks, which need capital injection from taxpayers' money every year to stay alive.

At the end of the first quarter of 2016, the nonperforming loans of state-owned commercial banks stood at 24.27 percent. In contrast, it was 6.2 percent in neighbouring India.

The default loan situation improved when the Awami League-led government assumed power in 2009, with the bad loan ratio coming down to single digit. But in June this year, it again crept up to double digits.

Economists and former central bankers have termed the situation alarming.

HISTORY OF DEFAULTS

Default loans have always been around, with some of the loans being classified as early as the 1970s.

At the time, the BB as well as the banks themselves classified the loans, and once they were realised they would be de-classified automatically.

But from the 1980s, classified loans started to rise, soaring as high as 35 percent, according to Khondkar Ibrahim Khaled, a former deputy governor of the central bank.

The situation mounted pressure on the BB to classify loans based on international best practices, and subsequently new rules were introduced in 1989.

Under the new rules, the size of the classified loans expanded significantly, said Helal Ahmed Chowdhury, a former managing director of Pubali Bank.

This prompted the government to undertake a reform project under the supervision of the World Bank in 1991-95.

In 1996, the Awami League-led government formed a banking reform committee, which found the default loan situation to be severe, especially at state banks.

In 1993, default loans at state banks stood at 32 percent and rose to 47 percent in 1999. And in some troubled private banks, classified loans were as high as 50 percent.

But total default loans at private banks came down to 29 percent from 35 percent during the period.

In its observation, the committee said that despite undertaking a host of reform initiatives in the banking sector, the desired result could not be achieved because of various problems and limitations.

About the state banks, it said they turned unprofitable and their net worth was negative as well.

It also said the huge default loans had turned the banking sector risky and became a barrier to boosting investment in the economy and making effective use of capital.

In 2003, the BB issued a notice on loan write-offs that allowed banks to somewhat shrink their default loans overnight.

Default loans stood at 13.23 percent of total loans in December 2007.

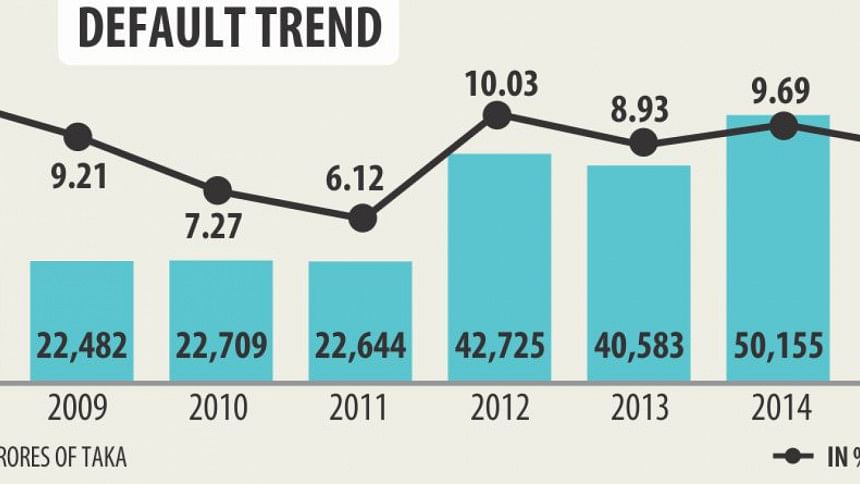

When the AL came to power in 2009, it was 9.21 percent. In 2011, it even came down to 6.12 percent.

The lower ratio of default loans though was not because of recovery; it was largely because of write-offs and rescheduling.

At the end of 2009, the amount of loans written-off was Tk 15,667 crore.

Since 2011, there have been ups and downs.

As of December 31, 2015, Tk 40,361 crore was written off.

In 2015, the BB, under pressure from large businesses, gave restructuring facility to loans upwards of Tk 500 crore. Under the facility, Tk 16,401 crore has been rescheduled.

FACTORS THAT ENCOURAGE DEFAULTS

Salehuddin Ahmed, a former BB governor, said the problem was created because the loans were given through anomalies and corrupt practices.

Furthermore, the loans were never monitored, and actions were not taken to realise them even when the banks came to know that they had become default.

“The factors that caused the default loans have not been removed -- the necessary actions have also not been taken.”

Ahmed said the banks are largely responsible for the default loans. They have continued to give loans in the same manner: under various influences and without looking at the quality of borrowers.

And when the loans become default, the banks find ways to keep provision against them.

The former BB governor said political influence works in two ways: when taking loans and preventing banks from taking actions, and when the loans turn bad.

“If credits are not extended properly to borrowers capable of using the money in the right business, the quality of assets created out of loan liabilities can never be ensured,” said Zahid Hussain, lead economist of the WB's Dhaka office.

Poor governance at bank boards, inadequate credit information, and inadequate financial statements of borrowers are major factors contributing to poor asset quality, according to an International Monetary Fund report on Bangladesh in January 2016.

Moreover, lengthy legal procedures involving disputed loans make it very difficult for banks to recover value from NPLs or their collateral, further exacerbating loan losses, the report said.

Chowdhury, a veteran banker, said loans can turn bad unintentionally, through external shocks such as the sudden fall in commodity prices.

ACHILLES' HEEL

The banking reforms committee of the mid-1990s had identified state banks as the most problematic area -- and nothing has changed in the two decades.

Once a high performer, BASIC Bank has been reduced to a bad bank after appointment of corrupt people on its board.

Another government controlled bank, Bangladesh Commerce Bank, which was set up in 1995, saw its default loans soar to 32 percent of its total loans in June this year.

The situation is the same in other state banks.

Since assuming office in 2009, the AL-led government in many cases appointed board members on political consideration, even though the last national banking advisory committee formed by the government recommended that a panel of qualified people should pick directors.

Khaled cited the reappointment of Agrani Bank Managing Director Abdul Hamid as a case in point.

The Banking Companies Act has made obtaining a “no-objection” letter from the central bank mandatory when appointing managing directors of both state and private banks.

For Hamid's reappointment, the BB never gave the letter because of corruption allegations against him, but the finance ministry still went ahead and reappointed him.

The Banking Division even justified the move by saying that the government is the owner of state banks, so it made the reappointment.

“The central bank could do nothing here. When the finance ministry defies the law to pave the way for appointing a corrupt person, then why will corruption not take place?” said Khaled.

He noted that loans may turn bad because of unrest or other unavoidable situations in the country. But when a loan is given out through corrupt practices, it becomes bad from the very first day.

Ahmed said the central bank should shoulder some of the blame as it has distanced itself to some extent from core banking.

There was a lack of monitoring and supervising of the banking system on the BB's part, and no follow-up actions were taken at the right time, he said.

IMPACT OF DEFAULTS

Hussain said the large and ever-increasing accumulation of non-performing and stressed assets in state-owned banks hinder their capacity to provide fresh loans.

The repeated application of rescheduling and write-offs for reducing classified loans on banks' balance sheets has not yielded the intended results yet.

“Such techniques work only when they are applied in truly deserving cases without repetition. Once you start rescheduling the rescheduled loans, a Pandora's box opens,” Hussain said.

It reduces the perceived cost of not repaying loans on time, thus encouraging and deepening the default culture, he added.

The IMF in January said the high NPLs, low loan recovery ratios and the correspondingly large provisions for loan losses are an important driver of interest rate spread in Bangladesh.

It is estimated that halving loan loss provisions from their end-2013 level (through an improvement in asset quality) would help bring down lending rates by 0.4 percentage points.

REMEDY

Khaled said one provision of the Banking Companies Act has to be changed.

According to the provision, the central bank can remove chairman, MD or board members and even dissolve the board and appoint administrator if their actions go against depositors or the banks.

At the same time, it is said that if the board members or the chairman are appointed by the government, the central bank will not be able to apply any power.

“It is an arbitrarily black law. How come two laws exist in the country? The law has to be amended and the central bank should be allowed to exercise its quasi-judicial power on all banks,” Khaled said.

He also said the Banking Division should be made void and a search committee formed with noted economists or former governors to appoint MDs or chairmen.

“Corruption has proliferated after the Banking Division was formed.”

He said the recapitalisation of state banks with taxpayers' money when they face a capital shortfall should be stopped. “The banks have to earn money to meet the shortfall.”

In a study, the Bangladesh Institute of Bank Management said unconditional recapitalisation provides no incentive for doing some deep surgery to repair the banks' damaged balance sheets.

In the long run, rising stress in the state banks will require more radical reforms in their structure of governance.

The fundamental problems with the state banks are the interdependence between banks and state-owned enterprises, the way that banks are run as SOEs, and the government's improper influences on the operations of SOEs and banks, the WB said.

Also, many private industrial companies have been hit by delays in making their investment projects operational due to unavailability of basic utility connections such as gas, water and electricity, leaving them unable to repay loans to SCBs.

“Though these problems have been around for a long time and are deeply rooted, they have never really been solved,” the WB said.

Without a thorough reform of the SOEs and the way that banks are run as SOEs, the problems with the banking system will remain, even after the banks are fully or partially relieved of current NPL, the Washington-based multilateral lender said.

Subsequently, it suggested strengthening the independence and accountability of state banks' boards, shoring up their balance sheets through recapitalisation conditional on improved loan recovery and temporary credit growth limits, and speeding completion of branch automation to strengthen financial reporting and efficiency.

It also called for enhancing financial sector regulation and supervision by strictly enforcing existing rules and avoiding regulatory forbearance; and completing implementation of risk-based supervision and contingency planning.

The WB called for improving the legal and financial framework for loan recovery.

The difficulties in realising collateral and lengthy dispute resolution processes have weakened the banks' ability to bring down NPLs.

“It is critical to institute simpler court procedures, alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, and asset management companies,” the WB said in April.

To ensure sustainable and prudent credit operations, more innovative approaches, along with judicial use of rescheduling and write-off, are needed to end the default culture, Hussain said.

“The wilful defaulters must be held accountable, not rewarded through rescheduling.”

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments