Monetary policy has been set free... but not really

While the government's latest monetary policy for the first half of fiscal year 2023-24 shows an attempt to be rational for the market, it lacks vigour to solve inflation and the dollar crisis. It deserves credit for bailing the lending rate cap – which prevailed for more than three years in defiance of economic reasonings – out of jail. For the first time in years, the exchange rate will be allowed to float on the basis of market supply and demand. Apparently, the Bangladesh Bank has embarked on a journey towards a free market economy after earning a release order from the finance ministry. But the freedom is conditional and more complicated – hence, the policy will be less effective in controlling inflation.

The apex business body in the country was strongly against removing the lending rate cap, and it said so incessantly. The reason is clear. Businesses can grab funds at zero real interest if the cap prevails. Technically, the real interest rate (borrowing rate minus inflation) was negative one percent since they could borrow at nine percent at a time when inflation hovered over 10 percent. Effectively, banks were giving them an extra one percent bonus if they took any loans. What a golden age of profit bonanza business tycoons enjoyed for more than a year, emboldened by the stubborn endorsement of the finance ministry.

Apparently, the Bangladesh Bank has been more independent to influence the lending rate after removing the cap, but this move has essentially legitimised the finance ministry's authority to influence the lending rate by incorporating the Treasury Bill (T-Bill) rate in determining the rates. Of course, this is an instance of financial innovation, and innovations are always welcome to help the nation escape from its poor performance in the global innovation index. But this is practically a trick to engage the ministry in Bangladesh Bank's decision-making and indulgence to fiscal incapacity which does not see any light at the end of the tunnel. Why?

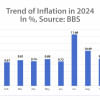

By removing the lending rate cap, the central bank has introduced SMART – the six-month moving average of the rates on Treasury Bills – which is now running at 7.1 percent. The government issues T-Bills – short-term money market instruments with 182 days' maturity – to fill up its budget deficit. The central bank arranges the auction among big banks and primary dealers where banks will buy the bills at a competitive yield rate while the government will try to give a rate as low as possible to minimise its burden. Bangladesh Bank has set the maximum lending rate for banks with a 3 percent margin above the T-Bill rate, making it 10.1 percent for now, for example. Banks can now lend funds at or below 10 percent at a time when inflation is 10 percent, making the real cost of borrowing funds just zero. This is not a sincere step to combat inflation.

Bangladesh Bank has imposed a new lending rate cap under the masquerade of the so-called SMART – a tricky innovation that is supposed to do more harm than good for central bank maneuverings and its image.

SMART is an unsmart move for indulging manipulation, political pressure, staggered decision making – which will all create more uncertainty for investors and banks. Bangladesh Bank will announce SMART monthly, and banks will allow their borrowers to ask for loans based on those ever-changing SMART, augmenting more bureaucracy and uncertainty in the domain of investment. This was unwarranted at a time when other central banks are simplifying lending rules and helping people understand how lending rates are dependent on the policy rate – which is the fed funds rate for the US and repo rate for Bangladesh.

The biggest influence on T-Bill rates is exerted from the government side – the finance ministry. The ministry can decide how much money it needs to collect from treasury bills and how much from treasury bonds. If its demand for cash is high, it must accept higher T-Bill rates and vice versa. If rates on selling long-term treasury bonds are comparatively profitable, the government will switch to selling more bonds and less bills. So, the ministry has the power of playing games with different rates. Bangladesh Bank's role here is to act as a mediator for the ministry's wish. Now lending rates, which were supposed to be solely decided by the central bank based on market observations, have been shifted to the control of the finance ministry. Is it a smart move towards central bank independence?

It would be smart to create a corridor for lending rates based on the repo rate which the central bank controls like any other central bank. Then lending rates would have been under the guardianship of the central bank, not the finance ministry. Bangladesh Bank could have declared a margin of, say, 6 percent above the repo rate of 6.5 percent, making the lending rate to be 12.5 percent maximum. Similarly, the deposit rate floor could have been 2 percent below the repo rate – the same as the reverse repo rate. Then the whole spectrum of interest rates would go up and down based on the judicious movement of the main policy rate control by the central bank. Losing the handle on rates is not a sign of intelligence either.

Bangladesh Bank has imposed a new lending rate cap under the masquerade of the so-called SMART – a tricky innovation that is supposed to do more harm than good for central bank maneuverings and its image. While the fed funds rate influences T-Bill in the US and this is true for other well-functioning economies as well, Bangladesh is heading towards a direction where T-Bill rates will one day influence the central bank rates. The new central bank leadership has endorsed that legitimacy without deeply thinking about its long-term consequences.

Announcing that the exchange rate will be market based lends more suspicion than certainty. Central bank officials commented that the dollar's value at Tk 108 is fairly a market price. If that is true, why does the rate fail to bring adequate remittances by discouraging the hundi business? Why are the reserves dwindling without any sign of correction? Why are some importers ready to offer even Tk 115 to bring their goods from overseas? Simply put, the rate controlled by Bangladesh Foreign Exchange Dealers' Association (BAFEDA) is defective, where the dollar is still undervalued, making the dollar crisis worse. Is a BAFEDA type controlling organisation needed if the exchange rate is really set to float?

The apparent freedom in Bangladesh Bank's monetary policy has a lot of black holes and the question arises whether it is the same old wine in a new bottle.

Dr Birupaksha Paul is a professor of economics at the State University of New York at Cortland in the US.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments