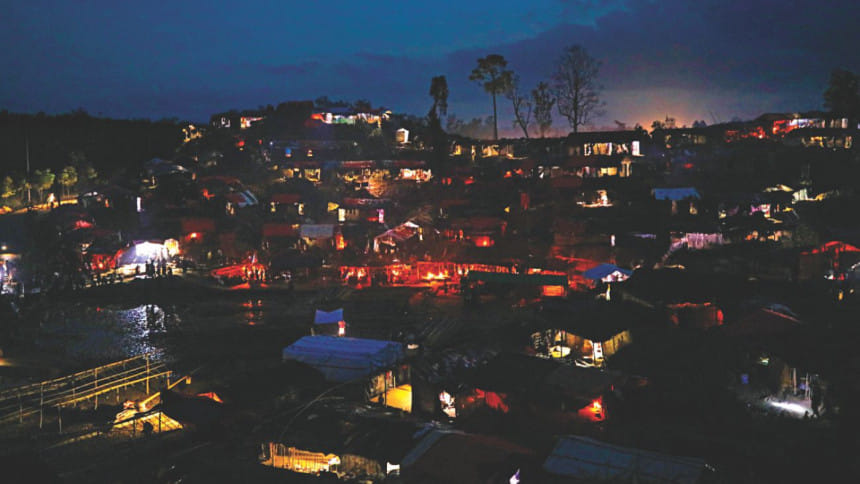

Night at a refugee camp

7:00pm

As the last relief truck departs, Shafiuallah Kata Pahar, a group of hillocks, reverts back to a strange sense of calm. People, carrying sacks of rice and packs of food, begin to return to their tents.

Suddenly, the hills seem to be dotted with fireflies. Lamps and candles masquerade as shining stars in the sky on a dark night, lighting up one by one.

After another hectic day of collecting relief and building homes, some retire to their beds. When darkness falls, there's nothing to do in the camps.

8:00pm

By now most families are done with their dinner of mostly dry food. A few have fashioned makeshift ovens to cook.

In a few minutes, a medical team from Darus Salam Mirpur arrives, packed with medicines. The last open shop, selling water, cold drinks, biscuits and cigarettes, also prepares to close for the night.

A few people, especially those who arrived yesterday or the day before, mill about on the roadside, waiting for relief. At night, people in luxury cars arrive to donate money.

Mehmudullah, a young farmer from Buthidaung sits on a bamboo stack beside the highway. As we approach him, he dives into his story. "We came yesterday morning. We do not have any tarpaulin for shade yet. We need money to buy materials to construct our tent," he says. He adds that his wife and children are sitting in their semi-constructed tent.

9:00pm

The night now grows darker. The entirety of Shafiullah Kata Pahar is cloaked in tranquility. Only the sound of a tube well being pumped breaks the silence from time to time. It can be heard but not seen.

Mehmedullah picks up the sound and begins to walk towards it. He turns on his torch to light his path. "Turn it off. Women are bathing here," a voice from the darkness warns.

Why are they bathing so late, a question is asked to the black. The voice now introduces himself as Ebadullah. "We just got this tube well yesterday. Many women have not bathed for days and have finally gotten an opportunity," he says.

Ebadullah, too, is waiting to take a bath.

Suddenly, the stillness is disturbed again as a crowd of people rush towards the highway where a bus has stopped.

Mehmedullah says that they are donating money.

We head towards the bus and see some bearded men in white panjabis and kurtas giving out 100 tk notes to the people. They also give bags of rice, potatoes, flattened rice and gur. More people are drawn to the crowd.

Soon, the men are ready to leave. As the bus speeds off, some stick their necks out of the windows and shout, "Pray to Allah. Things are going to be okay."

Mehmedullah returns, having gotten nothing.

9:30pm

We move ahead and catch up with Mohammed Hossain, a youth from Buthidaung, who says he once had a fishing boat and a net. He used to catch fish along with other fishermen and earned around 10,000 Myanmar kyat every day.

We ask what his plans are now. Hossain is unsure.

"There are many people in Bangladesh. I do not know what to do here. It is hard for even the locals to get work," says Mohammad Hossain.

10:30pm

Mohammad Hossain and Mehmudullah ask us to go to the top of the hill with them. Mehmudullah informs that most people here are from Buthidaung.

On the way up, we see the forested areas now cleared and the fallen trees. Equipped with a torch, we do not see much more but there is movement in many of the tents. The mosquitoes and the weather make sleep difficult to come.

On top of the hill, we find Md Rafiq's tent. He is currently engaged, talking over his mobile phone to someone in Myanmar. As Rafiq finishes his conversation, we ask who he was talking to.

"My sister in law. She is in Buthidaung. The roads there are now blocked and army patrol has increased so she cannot come," he says.

The mobile reception is better on top of the hill. Many people can be seen, ears glued to their phones, sometimes concern and sometimes a smile, on their face.

11:30pm

Walking downhill, people can be seen fanning themselves. The weather is sultry.

As we reach the bottom, a pickup stops in front of the approach of Shafiullah Kata Pahar. Around 20 people rush to the bus. They only throw a few packs of biscuits and go off.

12:01am

A young boy, Omar Sharif, is sleeping in an empty shop beside the road. He suddenly wakes up. We ask why he is here. He has come too far and lost his way, Omar says. He tries to go back to his slumber.

12:51am

By now the entirety of Shafiullah Kata has fallen asleep. We decide to check out the Bhagghona camp on plain land. It is muddy everywhere. A few babies can be heard crying. In the distance, we hear someone's radio playing.

We follow the noise and come across an elderly Rohingya woman listening to the Waj Mahfil of one Maulvi Masud. "He was very popular in Arakan," she says when asked about him. We move on.

2:30am

A few feet away, at Palongkhali union parishad office, the light remains switched on. A bunch of local people inside the office are grinding spices to cook khichuri in the morning as the government has recently opened a mass kitchen there.

3:00am

A jeep is seen at Balukhali camp. A known government official is sitting in the car distributing money. Seeing us, his jeep quickly speeds up and goes away. Strange.

4:00am

Near Balukhali camp, some people are sitting in an open field. Speaking to one Md Rafik, he informs that they had come from Buthidaung a few days ago. Rafiq's wife Mamtaz is lying under a polythene sheet with their children while Rafiq sits on a tree stump.

"Why are you sitting here," we ask. Rafiq says that they could not make any tent. The locals were asking for money to set up a tent.

Rafiq's wife Rehana comes out, and shows a side of her head which is swollen. She says relief workers had given her a tarpaulin but a local woman had beaten her up and taken it from her.

As dawn breaks and our night ends, we begin to leave. A local youth on a motorcycle informs that there are many people taking shelter in Palongkhali Primary School.

We find nearly five hundred newcomers in the school.

In the classroom, in the veranda everywhere there are people, lying down. As we approach them and begin to take some pictures, some lift their heads and watch us. They do not say a word.

They seem almost relaxed, probably after having already seen too much cruelty in Myanmar. They knew perhaps that the Bangladeshi people meant no harm.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments