Into hilsa mystery

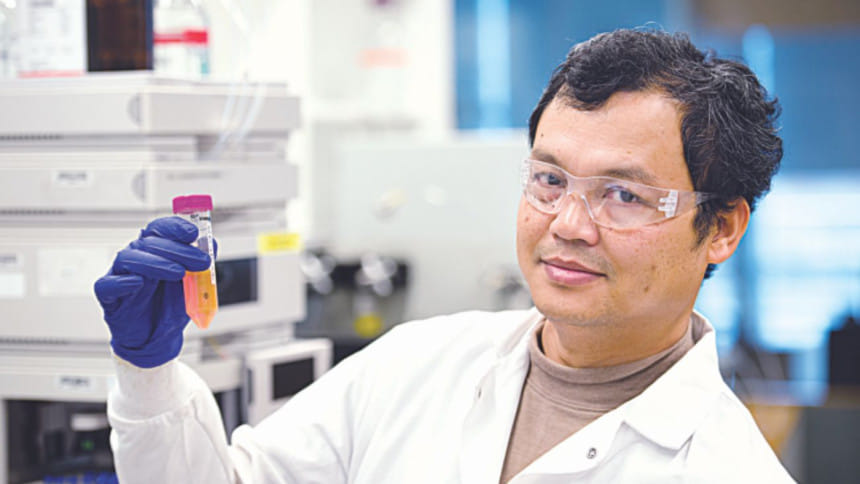

Dr Mong Sano Marma initiated the genome sequencing and proposed it to Prof Haseena Khan, who led the research. Mong also convinced his neighbour in the US, Dr Peter Ianakiev, who facilitated the genome sequencing at his research organisation for free.

What makes the Padma hilsa taste better than sea hilsa? Why does this silvery fish come to the river from the sea for spawning and then go back to the sea? How do they survive in both conditions? May be all these mysteries are going to be solved.

After jute, a group of Bangladeshi researchers have decoded the genome sequence of the country's national fish, opening up a new horizon to unlock the mysteries of its lifecycle.

The gene sequencing of hilsa shad (Tenualosa ilisha), which has come to be a part of the Bangalee culture, would help reveal many secrets of its lifecycle, including its ability to survive in sea water and fresh water, and thus can help conserve it.

It will also likely help reveal whether the fish can be domesticated, meaning if they could be cultivated in ponds or other waterbodies and thereby increase its production artificially.

Prof Haseena Khan of the biochemistry and molecular biology department at Dhaka University, who led the research, disclosed the matter to The Daily Star recently.

“The genome contains all the heredity information of any living being encoded in the molecules of deoxyribonucleic acid or DNA. Genome sequencing, therefore, means reading all the secrets of the life of a particular species written in its DNA,” said Prof Haseena, who was also a key Bangladeshi researcher of Jute genome sequencing.

This would give scientists some deeper insights into what kind of proteins make up the body structure that helps hilsa to live in fresh and sea water ecosystems, she said, adding that each biological and genetic character of a living being is connected to DNA or RNA (ribonucleic acid) codes.

“It also could in future be used to know how and when sex change occurs in this fish, since most of the larger hilsa caught in the rivers are female,” Prof Haseena noted.

Hilsa production has increased in recent years after imposing ban on catching brood hilsa and jatka (hilsa fry). Still, the most popular fish of the country that contributes around 12 percent of fish protein in Bangladesh are at risk of extinction as most of the rivers in the country are polluted and drying up.

In 2016-17, hilsa production stood at 4.96 lakh tonnes, up from just 2 lakh tonnes in 2002-03, according to the fisheries department.

The ban on hilsa fishing is placed during what traditional knowledge considers it to be their breeding period, as the period could not yet be ascertained scientifically.

Prof M Niamul Naser of DU's zoology department, who is also on the research team, said, “But now the genome sequence is going to help scientists to know about the life secrets, habitat preference and diseases of the fish. Also, its enzyme (coded by genes) would help us know about their food habit accurately at their life stages,” he added.

“We only know about some parasite of hilsa, but do not know anything about its diseases,” he said.

There have been many international researches about salmon, which also come to river from the sea.

“Now people know what changes in certain hormones drive salmons to come to the river from the sea. But we did not know much this for hilsa. This will help us to know that,” Prof Niamul said.

Also, it will help researchers know why the taste of hilsa from one region is different from those in another region.

HOW SCIENTISTS CAME TOGETHER

Bangladeshi scientists working in three continents worked together to decode the genome.

The idea first came to the mind of Bangladesh-origin biotechnologist Mong Sano Marma, a former student of Dhaka University who now works at a US-based molecular technology firm.

“Mong is working on genome decoding at his company. He thought that it would be great if he could decode the genome of hilsa as it is our national pride,” said Prof Haseena.

As the genome sequencing would be costly in his company, he approached his neighbour Dr Peter Ianakiev, a polish national, who heads Hera Bioscience, a contract research organisation in the US, that does next-generation sequencing.

Peter helped Mong to do the sequencing at his laboratory for free.

Mong first tried to do the sequence collecting hilsa samples from US shops. But it was in vain.

Other members of the research team are: Prof Mohammad Riazul Islam, Lecturer Farhana Tasnim Chowdhury, and young researchers Avizit Das, Oly Ahmed, Julia Nasrin, Tasnim Ehsan and Rifath Nehleen of the biochemistry and molecular biology department at DU.

Prof Niamul, who has long researched hilsa, helped the team to collect hilsa samples from seven different habitats -- deep sea, Meghna estuary, Padma-Meghna estuary, Jamuna, Brahmaputra, upper Padma and Hakaluki Haor.

The project began on September 10 last year and the samples were collected by September 22.

The team employed the most reliable methods of sample collection, advanced DNA preparation and sequencing techniques, Prof Haseena said.

“It required a year-long communications, detailed planning and coordination among scientists living in three continents, and weeks of work using powerful computers to interpret a large dataset,” she added.

The DNA samples along with the RNA from different organs of the collected fish were sent to the lab in the USA on January 11 this year.

“It was not possible for Peter to decode seven DNA samples as he was giving the service free of cost. In order to have a reference dataset to start with, it was decided to sequence Padma hilsa and RNA sequencing of both Padma and deep sea,” said Prof Haseena.

The team discovered that the genetic history of hilsa fish is written by about one billion letters (base pair – chemical units) and contains about 30,000 genes.

Given the data size, a super computer was needed for analysis.

The bioinformatic or computer-based analysis of the huge data was done by AKM Abdul Baten, a Bangladesh-origin Bioinformatician who used to work at the Southern Cross University in Australia.

Baten had access to a super computer and he helped in getting the DNA data analysed. As he later moved to New Zealand, it was not possible for him to analyse the RNA data further.

The DNA sequencing ended on March 1 this year while the DNA assembly ended just last month.

Prof Haseena said they were now analysing RNA data at the Molecular Biology Lab of DU using the computer facilities of Bangladesh Research and Education Network (BdREN) as no labs at the DU has that facility.

After the RNA analysis, the researchers would able to know which genes function in the two different conditions -- sea and fresh waters.

BANGLADESH TO GET HILSA PATENT

Last year, Bangladesh got the geographical indication (GI) right of hilsa. With the genome decoding, the country can now apply for the patent registration.

This is why the researchers have not published their findings yet.

Asked whether they would go for publication, Prof Haseena said the data had to be submitted at the website of GenBank sequence database first.

“They would give an accession number and then an international forum would publish it.”

With the completion of the genome sequencing of hilsa by her own scientists, Bangladesh can also apply for registration for the intellectual property rights, she added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments