Great leaps forward in ice cream history

It's one of the most complex food products you'll ever consume: a thermodynamic miracle that contains all three states of matter — solid, liquid, and gas — at the same time. And yet no birthday party, beach trip, or Fourth of July celebration is complete without a scoop or two.

That's right — in this episode of Gastropod, we serve up a big bowl of delicious ice cream, topped with the hot fudge sauce of history and a sprinkling of science, reports digg.com.

Grab your spoons and join us as we bust ice-cream origin myths, dig into the science behind brain freeze, and track down a chunk of pricey whale poo in order to recreate the earliest published ice cream recipe.

Colder than ice

Contrary to popular myth, ice cream was not brought to Italy from China by Marco Polo, and then introduced to France by Catherine de Medici. In fact, it is a delicious love-child, born of the union between a culinary tradition of custards and burnt creams in medieval Northern Europe, and the fruity, floral, sherbets (sharbat in Persian) that were typically served over ice as a refreshing drink in the Middle East.

For millennia, humankind has gathered and stored natural ice and snow in order to preserve food and chill drinks — snow was sold in the markets of Athens in the fifth century, and wealthy Romans, inspired by Middle Eastern sherbets, recklessly disobeyed the medical advice of their day by mixing ice chips to their wine. But simply adding ice is not enough to freeze sherbet into sorbet: to do that required the creation of a substance that was colder than ice.

That scientific breakthrough occurred in Naples, when Giambattista della Porta, a Renaissance-era polymath who had already invented a new cryptographic system and perfected the camera obscura, decided to turn his attention to the science of freezing. By combining snow with saltpeter (potassium nitrate, which was manufactured in bulk as an explosive for military use) in a bucket, he managed to make a mixture that was cold enough that a sealed bottle of water submerged in it would turn to ice. It worked because the saltpeter draws the frozen water in the snow out from its crystalline structure, causing it to melt.

The phase change from solid to liquid requires energy in the form of heat, lowering the temperature of the resulting salty slush to about 0ºF — plenty cold enough to freeze water.

Della Porta immediately tried his new technique out on a decanter of wine, which didn't freeze solid because of ethanol's low freezing point. Nonetheless, according to food writer Jeri Quinzio, his wine slushies were "a big hit on Italian banquet tables" of the late 1500s and early 1600s. By the 1620s, however, scientists and then cooks had worked out that della Porta's technique worked even better using salt, rather than saltpeter, and that 0ºF was cold enough to freeze the perfumed sherbets of the Middle East into the first sorbets.

Before too long, an anonymous confectioner had the bright idea to see whether the same trick worked with a custard mix — and ice cream was born. The first recorded recipe comes from an unpublished cookbook written by an Englishwoman, Lady Anne Fanshawe, in 1665. Quinzio speculates that Fanshawe first encountered what she called "Icy Cream" in Spain, where her husband served as ambassador.

In her recipe, she suggests flavoring it with orange-flower water (in a nod to its Middle Eastern roots), mace (a cousin of nutmeg), or ambergris—a greasy, odorous lump of fossilized squid beaks, mucus, and compacted fecal matter formed in the intestines of some sperm whales that, for thousands of years, has been prized as a perfume, spice, and even medicine. In the episode, historical gastronomist Sarah Lohman scored some wildly expensive and technically illegal ambergris in order to recreate Lady Anne Fanshawe's ice cream; listen in to hear our verdict on the taste.

Let them eat ice cream

Those early ice creams were a luxury item, found only on the tables of the aristocracy. Its journey to becoming America's favorite dessert involved several more steps, including the repeal of heavy salt taxes, the huge reduction in the price of sugar brought about by the Atlantic slave trade, and even the French Revolution — as their aristocratic masters met the guillotine, fancy confectioners spread out across Europe, bringing the secrets of ice cream-making with them. Many opened cafes and restaurants, making ice cream accessible to the masses.

But the real breakthrough in the democratization of ice cream came thanks to Frederick Tudor, a Bostonian who had the brilliant idea of turning New England's wealth of natural ice into a business. His first shipment set sail from Boston harbor in February 1806, bound for Martinique. Amazingly, a fair amount of his ice survived the journey — but upon arrival at the port of St. Pierre, Tudor encountered another challenge.

There were no ice houses in Martinique, and the locals had no idea what to do with the lumps of melting ice that this peculiar American was trying to sell them. In desperation, Tudor used a large portion of his cargo to make ice cream — which was a huge hit, earning him the equivalent of $30,000 today.

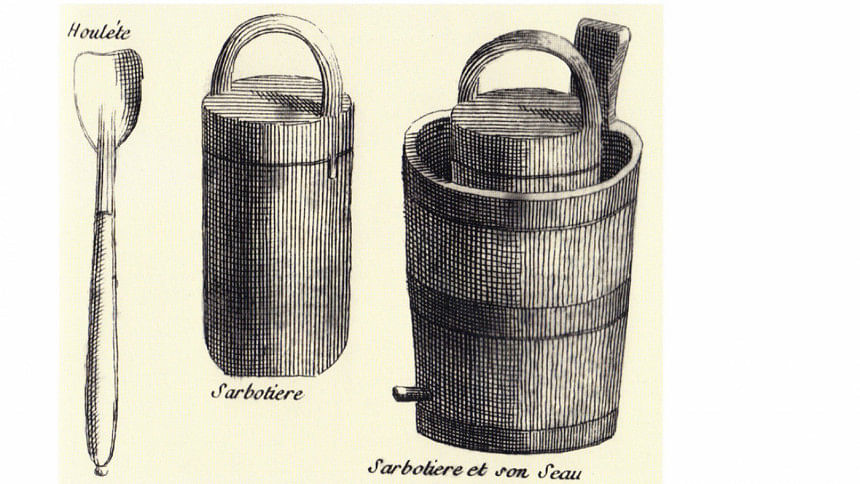

By the mid-1800s, Tudor had perfected the art of harvesting, storing, and shipping ice, and the resulting economies of scale made it affordable for the majority of Americans. Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, a woman named Nancy Johnson took the next great leap in ice cream technology, by inventing the first hand-cranked ice cream-maker. Previously, making ice cream was a tedious and fiddly process that involved fishing the pot of custard out of the bucket of freezing brine at regular intervals during the freezing process, in order to pry off the lid and stir it.

Johnson's patented device had a crank on the outside of the barrel, attached to a churn on the inside, with the salty slush enclosed in a slim gap between the two. The ability to churn the ice cream without removing it from the bucket was a significant step forward in both convenience and quality, allowing for a smoother texture, and Johnson's machine quickly caught on. With the addition of a motor to power the churn and an even colder chemical inside the barrel walls, today's ice cream-makers still work exactly the same way.

The New Golden Age

In the twentieth century, ice cream had its ups, including the invention of the popsicle and the Eskimo Pie, but also its downs, as industrial cost-cutting drove a reduction in the quality of ingredients. Today, however, ice cream is entering a new golden age. A new generation of artisanal ice cream-makers is experimenting with adventurous and unusual flavor combinations: listeners wrote in to tell us about poutine-flavored ice cream in Portland, chocolate-chile in Boston, and sweet corn with blackberry swirl in Cleveland. Meanwhile, scientists are developing an entirely new vocabulary of ice cream textures, from fizzy to stretchy.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments