Partition 1947: The tears that still bind

Ten years ago I met Gazi in Bangladesh's Satkhira region, in a small island called Koikhali. He had come with his immediate family about 60 years back, at the stroke of midnight, with nothing but the clothes on his back. Although in the beginning he had been able to keep in touch with the rest of his family in India, he had not heard from them in many years. The Indian government had started building a wall and anyone trying to travel to the other side without official documentation was beaten, locked-up or killed. He told me about his family and the circumstances in which he had left; so I, who had a passport and travel permits, decided to visit his 90-year-old brother and family back in India. Following the address he gave me, I went to a village in the Basirhat subdivision in the district of the North 24 Parganas of West Bengal. When I located the house and found the old man, I showed him a photo of his brother and his children. His eyes started to water. We struck up a conversation and I probed, 'Why did you not leave?'

After some moments spent in silence he said, 'Why did he leave?—that's the question you should ask and I can't answer it for him.'

The book The Bengal Diaspora: Rethinking Muslim Migration co-authored by Joya Chatterji, Claire Alexander and myself (Routledge, 2015), was created out of a desire to find the answers to such questions, questions that had for too long remained both un-asked and un-answered.

In 2005, all three of us were based at the London School of Economics, albeit in different departments. Joya was in History, Claire in Sociology, and myself in Anthropology. One afternoon, we decided to meet for tea and Joya suggested, 'How about we do a project together?'

Joya had written at length about the Bengal Partition in her book Bengal Divided and explained how those who have worked on the Partition of Bengal, had primarily focused on the Hindus—and that too chiefly on those from the upper and middle echelons of society. Poorer migrants and refugees, particularly Muslims, had not really been the focus of anyone's analysis, and those who were internally displaced were literally invisible, both in public records as well as scholarly articles. These groups of migrants remained within their region of origin, on either sides of the border and in enclaves or the ghettoes of Kolkata, Dhaka, Chittagong, etc. their position still ambiguous and uncertain.

'Annu does the anthro bit, Claire does the socio and UK bit, and I do the history bit. For that you'd have to go to Bangladesh', concluded Joya.

I was up for it in a beat!

You can't grow up on either side of the Bengali border without thinking of the other. For the older generation, this was usually with nostalgia and resentment, for the younger generation, with curiosity and suspicion. Are they like us? How different are they? We had a Communist leader for the longest time and they have had generals replacing each other—sometimes pretty bloodily. Are they really Bengali or are they really more Hindu/Muslim?

As a BA student I had travelled to Bangladesh to work on Bhaoaiya and Bhatiyali songs in what then seemed long ago. I had, for this purpose, also travelled to northern West Bengal and Assam. On both sides of the border, my interlocutors' biggest concern was that my parents had let me travel, on my own, to this 'foreign land'. Those I met, in their concern, often took me under their wing and decided to accompany me to meet people they thought I should interview. I remembered a few happy weeks. This had been in 1996.

Fast forward to 2006 and the funding for our project had come through—generously provided by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. I was soon returning to this country, except that now, in 2007, I had lived in London for 10 years and had very supportive friends who introduced me to their extended family and friends in Bangladesh. I was flying to Bangladesh inspired by this group of friends who were linked to Drishtipat, an online portal on human rights, and they ensured that my second arrival in Bangladesh felt like a sort of homecoming. And yet, because we had not learnt and lived history in the same way, Bangladesh often felt very alien too.

'So what is your work about?' I would be asked.

'It is about Partition refugees from India.' I would reply.

'You must be working on the Biharis then,' would come the quick response.

'Some, yes. But the majority of refugees were Bengalis, so I'm mainly working on Bengalis who came from 'the other side.'

A lot of the time I was met with disbelief.

'But they came from India, they must be Biharis,' my interlocutors would insist.

'Most Indian refugees to East Pakistan were Bengalis,' I would maintain.

'Really? Where do you find them?'

'All over Bangladesh really—the more educated ones in universities, the poorer, less-connected ones in camps along the Bangladesh border.'

'Camps? Then you're surely talking about Biharis.'

'Yes, camps and they're very much Bengali. I know which villages they came from in West Bengal and they do not know a word of Urdu. They're Bengalis, trust me.'

The conversation would then veer on to who is a 'Bengali/Bangali.' I had grown up in West Bengal where Bengalis, whether urban or rural, routinely refer to (Bengali) Hindus as 'Bangali', to (both Bengali and non-Bengali) Muslims as 'Muslims' and to everyone else as 'aw-bangali'; here it was the reverse, Bengali Muslims, especially the ones who lived in villages and small towns, called themselves 'Bangali', the (Bengali) Hindus were 'Hindus' and the others were either 'Bihari', 'Pahari' or 'Bideshi.' A Kolkata friend shared how when she insisted she was 'Bangali', whether it was the rickshawala or a university professor, her claims to her identity would be brushed aside with a gentle smile saying, 'No, you're Indian'.

'Don't you think I know what I am?' she'd retort.

Identity, specifically Bengali identity and who was versus who wasn't, was huge here. Conversations often turned to who was more Bengali, the Bangladeshis or the West Bengalis. Who had better Rabindra Sangeet and Nazrul Geeti singers? Who had better contemporary singers? Who had the better saris? Who had the better sweets? Who had better sense of Bengali hospitality? Who had the sweetest words? 'You win, hands down, except for the sweets—you guys drove all the moyras away.' 'You might have to go hungry once your Farakka has dried up our rivers and we can't send you fish anymore.' The ripostes would fly hard-hitting and biting.

So, who is a Bengali? Why does this have to be a competition? The British legacy was to leave Bengal in tatters—not just politically and economically, but also culturally. It often felt as if for Bangladeshis everything had begun with 1971, with the 'Bangali' identity having germinated in the Language Movement. What was elided was our subjugation by the British, the Bengal famine, the struggle led by our freedom fighters, our common partition, the battle led by the person who gave us both our national anthems to keep us united, the trauma West Bengalis had suffered when entire areas of Calcutta were suddenly taken over by successive multitudes of East Bengali refugees—not once, but twice. For West Bengalis, the more important date was 1947, for Bangladeshis, it was 1971. But how could one, on either side of the border, cherish the one and not the other?

" So, who is a Bengali? Why does this have to be a competition? The British legacy was to leave Bengal in tatters—not just politically and economically, but also culturally. It often felt as if for Bangladeshis everything had begun with 1971, with the 'Bangali' identity having germinated in the Language Movement.

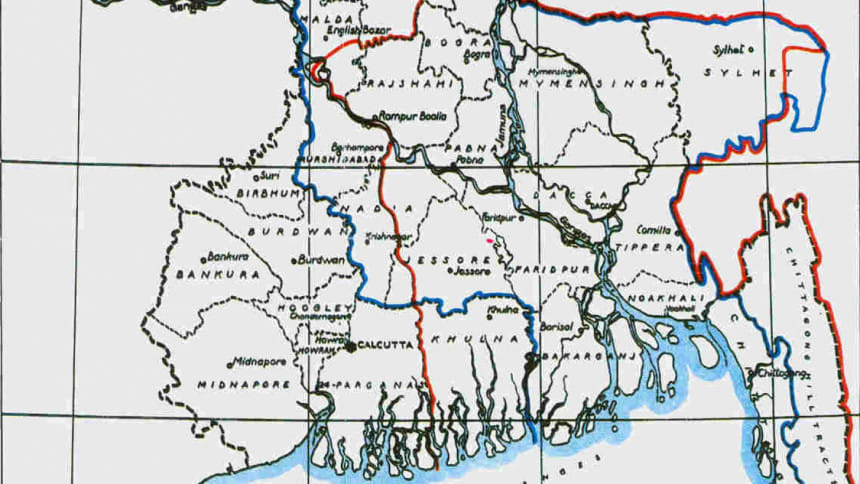

These two political lacerations further imperilled, within a span of less than 25 years, the already famine-frayed fabric of multi-religious, multi-ethnic, multi-caste, Bengal Delta. In one of the world's most densely populated regions, these two gashes generated the largest numbers of migrants in the world. About 20 million Muslims and Hindus—about a third of the region's population in 1947—sought shelter across new borders, fleeing the 'wrong' country to settle in the 'right', almost all of them resettling in the Bengal Delta itself, while another 20 million were internally displaced within the new national borders. This displacement of population experienced by the Bengal Delta experienced, probably the largest the world has ever known, had profound consequences for the region. Our study tried to understand what the consequences of this displacement between the two nation-states of India and Bangladesh were. We also looked at those who left their village or town to go settle in another (because they suddenly happened to be a religious minority in their area) but remained within the confines of the nation-state in which they had been born. Who left for the UK and why?

Most, if not all, of the studies on Bengali migration have focused on Hindus leaving East Pakistan and later Bangladesh for India, and never the other way around. This is because between 1947 and 1971, for every three Hindus leaving East Pakistan, about one Muslim was leaving eastern India; but countless others, especially Biharis, had come and built the railways at the turn of the 19th century and had stayed on to man the railways of eastern Bengal. Our work tries to address the silence over studies on the Muslim migrants from India. It also tries to challenge the Eurocentric bias of looking at migration as if it were, so to speak, a 'northern' problem. The number of people from this region, or anywhere in the South really, who have moved overseas is comparatively minimal. What we address in the book is how the South is not just a source of migration, but its pre-eminent destination. And this is not just for the Bengal diaspora, this is worldwide. South-South diasporas are the largest in the world, yet these huge migrations have remained overlooked by both scholars and the media.

By looking at the Bengal diaspora through the histories of very ordinary people, we trace the intersections between 'small' family histories and personal lives and 'large' transnational and national contexts. We highlight the very personal stories of migrants in conjuncture with the grand sweep of history. Thus, the book is, so to speak, a portrait of a South Asian diaspora 'from below'. How does one 'uncover the hidden stories of diaspora'?—The 'unofficial, undocumented, and unauthorised accounts of the unheard majority, including women, refugees, illicit migrants, and stateless people, the unnumbered and faceless poor who live below the radar of policy and politics as well as of academic scrutiny'? (p. 10).

Our book also highlights how migration into the region started long before the Partition of India. Between 1911 and 1931, for example, the eastern zone consistently recorded the highest number of internal immigrants and emigrants in British India. This was true both for males and females. The census figures suggest that by 1921, almost one in 10 of India's population, or some 30 million people, were internal migrants. In other words, in 1921, the number of people who were enumerated as internal migrants totalled more than the total number of journeys overseas migrants made over the course of an entire century! (p.35) By 1931, six million people had moved within and from the greater Bengal region (p. 28). This is already twice as large as the entire Indian diaspora worldwide in 1947! Our study supports Aristide Zolberg's two most significant claims: first, that 'nation-making is a refugee generating process', and second, that the vast majority of the world's refugees, since the Second World War, have stayed within their regions of origin in the developing world, with only a tiny minority migrating to the countries of the industrialised West (Zolberg and Benda [eds] Global Migrants, Global Refugees, 2001:9). Like Zolberg, we too observed that where refugees did cross national borders, most stayed close to the borders of their countries of origin.

While walking away from Gazi's 90-year-old brother's place in India, I was waylaid by a woman who pulled out a photo of a young bride. 'You see', she explained once the preliminary introductory talk over, 'I found a good man in Satkhira and married my daughter to him. I've lost her number and am sick with worry for her as she hasn't called in two months. I've heard that you have a passport, do you think you could look her up next time you're in Satkhira? Tell her that her mother prays for her every day.'

Annu Jalais is an anthropologist working on the human-animal interface, migration and Bengali identity, and climate change focusing particularly on Bangladesh and India. She is the author of Forest of Tigers: People, Politics and Environment in the Sundarbans (Routledge, 2010) and the co-author of The Bengal Diaspora: Rethinking Muslim Migration (Routledge, 2015), and is Assistant Professor at the National University of Singapore.

Comments