From postmemory to post-amnesia

In December 2012, I attended the wedding of a cousin in Dhaka, Bangladesh. She was marrying a young man from the same city, whom she had known for quite a few years and whose family, not very coincidentally, was also known to mine. As all weddings in my extended family, divided across Pakistan, Bangladesh and India, and spread out now across Europe, North America and Australasia, the wedding was an occasion to reconnect and remember the threads that bind us: a pair of great-grandparents, Khan Bahadur Kabiruddin Ahmed and his wife Sajeda Begum, and their home, Kabir Bhaban, in Faridpur of East Bengal, then East Pakistan, and finally Bangladesh. But it was also an occasion to remember less obvious connections.

" With the failure of the promise of Pakistan and the new pain of cultural domination leading to ethnic cleansing of genocidal proportions, the new nation of Bangladesh made a second forgetting imperative—their own prior investment within the project of Pakistan.

The day before the wedding, gifts, mostly of saris and jewellery, were sent over to the bride. The jewellery included some elegant and striking pieces which belonged to the bridegroom's grandmother. His grandfather had been a well-known diplomat and, evidently, a connoisseur of fine things. The collection his wife was passing on to her new granddaughter-in-law included pieces from all across Asia—as confirmed by their styles and also the leather boxes in which they were lovingly encased, which had branded on to them or stamped on their silk linings the names and addresses of specific jewellers. Many of these boxes revealed themselves as bearing addresses from Pakistan. Closer scrutiny revealed further that some of these Pakistani boxes had been recycled to accommodate jewellery that was of non-Pakistani provenance.

Today, I want to tease out the story of why these jewel boxes had been preserved, sometimes independent of their contents, for several decades; why they had travelled from Pakistan to Bangladesh; and what it meant for an older woman to bring them out at a moment of extreme personal and familial significance—the first wedding of a grandchild. I want us to think about disappeared spaces, about memories gone underground, about links that have been broken, and about the persistence and intergenerational transmission of affect. I want, in short, to think about Partition and collective memory. And I want to do so through a perspective that, despite the proliferation of scholarship on both Partition and the War of Bangladesh's Liberation, is not often deployed: a perspective that deploys 1947 and 1971 as linked events.

My approach to Partition as a memorial event rests on a simple axiom, which is at the heart of what I want to communicate to you today: To know better, if not fully, how we feel (about) Partition, we cannot ignore 1971. And to pay attention to 1971 is to remember anew a singular phenomenon: East Pakistan. This cartographic entity came into existence in 1947—or, more accurately, 1955. That year, the new state of Pakistan renamed as East Pakistan its eastern Wing, encompassing the known from British times as East Bengal. It ceased to exist in 1971, when the third successor state to British India, Bangladesh, was created after a violent civil war between the Pakistani nation-state and its eastern wing. The transformation of East Pakistan into Bangladesh also meant the transformation of West Pakistan into Pakistan, plain and simple. For India, it meant a new geopolitical valence for its eastern front.

I remind you of facts that you may already know well in order to emphasise that which often goes unnoticed in discussion on these two events of nation-formation through collective, physical and epistemic violence: the conundrum that was East Pakistan, and the hauntology that attends its erasure from the map. East Pakistan is a spectral presence from which we may extrapolate patterns of forgetting and remembering that are particular to modern South Asia. These patterns have been shaped by the interlinked nature of the foundational moments for postcolonial nation-states of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh; they have also been shaped by processes of modernisation and movement that were set into motion before 1947 and which continued until 1971. By attending to these specificities, we bring to memory studies and partition studies a clearer understanding of post-Partition memory work in South Asia.

One way in which I have attempted to do so is to extend Marianne Hirsch's influential concept of 'postmemory'. Hirsch developed this concept through her work on the intergenerational transmission of collective trauma across several generations of Holocaust survivors, focusing on Maus and her family photo albums. Hirsch's postmemory encapsulates our uncanny ability to 'remember' traumatic events which we did not personally experience, but stories of which have been narrated to us by parents or grandparents. As literary and cultural artefacts, postmemorial creations draw attention to the self-conscious telling of those stories, to the processes of re-memorialisation. Recently, Hirsch has presented the scholar herself as a postmemorial subject, by entwining memoir, intergenerational divergences and historiography in a moving account of visiting her ancestral home of Chernowitz with her husband and parents.

Like many of us here, I have found Hirsch's postmemory a deeply useful tool for my attempts to articulate the post-Partition memorial landscape. Indeed, when I started writing my book on the subject, postmemory was so central to my thinking that I wrote to Marianne asking her permission to use the word in my title. But as I began writing, I realised that 'postmemory' would not do. The Holocaust and Partition share a basic similarity as epochal, limiting, twentieth-century events, but there are also basic dissimilarities between them, and between their repercussions. While the similarities had drawn me to the term 'postmemory', the divergences now compelled me to think of a new term. I came up with 'post-amnesia'. Whereas postmemory signals the transmission of trauma through intergenerational remembering, post-amnesia conveys the transmission of trauma through intergenerational forgetting. It is, if you like, postmemory which has skipped a generation.

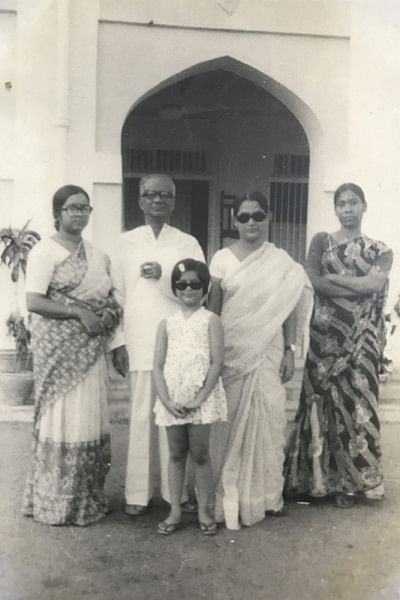

Hirsch's intergenerational model remains important for me, but more than the parent-child relationship, I am interested in the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren. Inasmuch as parents are the conduit between the two, they are important, too, but I'm fascinated by the pattern of remembering, forgetting, and re-membering that the three generations represent. Of course, these three generations are present in any social configuration, and, accordingly, are implicated in any consideration of the long-term effects of collective trauma. But postcolonial South Asia is marked by a particular congruence of generations and foundational moments. If the generation that experienced 1947 as young adults is 'generation 1', the subsequent 'generation 2' is that which experienced 1971 as young adults. 'Generation 3' experienced neither 1947 nor 1971 personally, but through post-amnesia.

Partition's post-amnesia for me, then, is the response to Partition and 1971 by Partition's grandchildren, and that is a subjectivity that defines me as a scholar as well. Its emotional centre is East Pakistan, a space that existed only to be transformed into the nation which owes its existence to a two-stage process, with each stage underpinned by a radically different ideology. Bangla-desh, 'the land of the Bengalis', was founded on Bengali cultural pride, but its borders derived from Partition's division of Bengal, and British India, on religious grounds. From supporting theological nationalism to rejecting it in for an ethno-cultural nationalism— this drastic ideological flip was further complicated by the cartographic continuity accompanying geopolitical transformation. East Pakistan as a trace is a persistent reminder of these complications.

So how does post-amnesia, as a form of cultural memory, attach itself to East Pakistan? Let me return to the jewel boxes with which I began. The jewel box opens to reveal not merely the heirlooms being passed on from a grandmother to her grandson's bride: it announces, in a bedroom in Dhaka, 'Patiala Jewellers, Rawalpindi'. In doing so, it takes us back from 2012, when Dhaka is the capital of Bangladesh, to the 1950s, when Dhaka was the capital of East Pakistan. This was a time when Bengali civil servants, who had opted for Pakistan rather than Bangladesh for a variety of reasons, including the prospects of brighter careers, found themselves posted to the Western wing in places such as Rawalpindi. This was a time when such places were not associated with Af-Pak, Kalashnikovs and the Taliban, but with parties where the glamorous wife of a Bengali civil servant of the nation of Pakistan could wear daring sleeveless sari blouses worn with diamond ear studs bought at Patiala jewellers.

'Forever', says Mireille Rosello, speaking of what she calls 'narratives of reparation', '[forever] the relic testifies'. I want us to think of this jewel box as a relic of a time that is easier to forget from the horizon of the geopolitical present—1947-1971. This was a time when the generation that decided to forge one set of affiliations in place of others—the generation that did not just experience, but made Partition happen through their choices—busied themselves in the task of nation-building across the postcolonial landscape. The Bengali elites in West Pakistan, participating in various state institutions from academia to the Foreign and other Civil services, exemplify this mobilisation of busy-ness to forget the pain of Partition. With the failure of the promise of Pakistan and the new pain of cultural domination leading to ethnic cleansing of genocidal proportions, the new nation of Bangladesh made a second forgetting imperative—their own prior investment within the project of Pakistan.

For both Pakistan and Bangladesh, the time between 1947 and 1971 was best forgotten. And what better condensation of amnesia than the map of East Pakistan, a page fallen out of the world's atlas (to paraphrase Amitav Ghosh), but simultaneously transformed into the identical map of Bangladesh? It was clamped shut, out of view, like the earrings in the jewel box, together with memories of parties, youth, and beauty in the days that were meant to be the proto-nation's darkest hour. But when the grandson's slender bride reminded an older woman of her slender sari blouses of yore (which she also bequeathed to my cousin), memory's box opens to reveal the affiliations, longings, memories and attachments that cannot be accommodated within nationalist teleologies.

It is the nature of the fetish to substitute for an original lack, the pain of which is so disabling that the act of substitution becomes a necessary distraction. The process signals melancholia as Freud defined it; from this perspective, the jewel box is a fetish that, through its partially-hidden inscription of 'Patiala Jewellers, Rawalpindi', both distracts and defers. Yet passing on the box, its contents and its message from one generation to the next can also be re-interpreted in terms of what Ranjana Khanna, recuperating Freud's original schema, calls 'critical melancholia'. In this reading, the message that is encrypted in the box is an invitation to the grandchildren to revisit the past which neither the grandparents nor the parents can, for reasons of self-preservation. Indeed, revisiting and reparation need not take narrative paths. Wearing the ear studs is a somatic re-membering that initiates new modes of intergenerational reconciliation.

" The informant from the past had herself been present in Rawalpindi, Murree, Karachi and other places in West Pakistan as a young woman, before the War of Liberation reshaped cartographies and personalities alike. And if West Pakistan is to be remembered, so must its twin, East Pakistan, which, in 1971, became Bangladesh.

According to post-Freudian psychoanalysis, critical melancholia takes the form of psychic partitions that progressively disguise the root cause of trauma but leave recondite verbal clues by creating layered 'shells' around trauma's 'kernel'. One such clue is provided by 'Patiala Jewellers, Rawalpindi'. Rawalpindi, a city in Pakistan's North-West Frontier; Patiala, a city in the plains of Indian Punjab: another trace that persists despite amnesia. Like countless other shop names recalling pre-Partition existences, 'Patiala' probably commemorates where the owners of this Rawalpindi jeweller family lived before 1947. The shop within which flourished the transplanted craftsmanship that created the ear studs, encrusts memory with the fruits of labour, but cannot help proclaim on its facades and silk linings the places perforce left behind.

This box that fetches up on the bed of a bride, comfortable and secure in her identity as Bangladeshi, as indeed is the bridegroom in his, and her cousin in her own Indian-ness, is nevertheless a message in a bottle, that unsettles the certainties of the present and feeds the curiosities of the generation of Partition's grandchildren. Here it is the parental generation—generation 2—that intervenes to fill in the gaps with stories of the grandmother's glamorous young self in Rawalpindi, accoutred with sleeveless sari blouses and elegant jewellery that have since been carefully stored away, waiting for the appropriate moment to resurface. The informant from the past had herself been present in Rawalpindi, Murree, Karachi and other places in West Pakistan as a young woman, before the War of Liberation reshaped cartographies and personalities alike. And if West Pakistan is to be remembered, so must its twin, East Pakistan, which, in 1971, became Bangladesh.

In its existence, disappearance, and spectral remainders, East Pakistan powers the narratives large and small that I seek to bring forth through analysis of the full gamut of cultural production—from academic journals on archaeology to Facebook posts. These are narratives that are often obscured or marginalised by the exclusionary teleologies of the nation-state or of religious identity, or even of ethnie. Beyond these teleologies, I want to demonstrate, lie affiliations which form a matrix of affects and identifications, which the post-Partition subject selectively mobilises to inscribe herself on to the map, literally and figuratively. Indeed, the affective utility of East Pakistan is to draw out webs of affiliation across Pakistan, Bangladesh and India, thereby reminding us that we as post-Partition subjects, have actually been formed out of a complex affective intersubjectivity.

This intersubjectivity resurfaces at contingent moments, as we saw with my chancing upon a jewel box that had moved with its owner from West Pakistan to Bangladesh and whose creators had themselves moved, earlier, from partitioned Punjab to West Pakistan. Noting this triangulation, joining the dots, is to engage with what Michael Rothberg has called 'multidirectional memory'. This conceptualisation of memory work recognises the interconnectedness of traumatic events on a large scale without succumbing to competitive claims of 'my trauma was worse than yours'. Rothberg talks about multidirectional memories which connect the Holocaust and colonialism, but his model is incredibly useful for thinking through the relationship between 1947 and 1971, and between successive waves of memory and forgetting these engender.

Acknowledging the multidirectionality of cultural memory is to open the door to new ways of thinking about Partition(s) as well as seeking emotionally sustainable models for reparation and healing. East Pakistan is, in this context, an exemplary shared lost space for all three nations, as the artwork Bloodlines, created by Pakistani artist Iftikhar Dadi and Indian artist Nalini Malani, suggests. Here, red sequinned lines demarcate the border between India and Bangladesh, visualising the traumatic relationship of cartographic lines to the multiple significations of 'blood'— kinship, violence, rootedness. But it also inserts Bangladesh within an Indo-Pak project that presents the search for the past as a multifaceted type of questioning. That search returns us all to the space defined by bloodlines, East Pakistan. Remembering why it has to be but also cannot be forgotten is a necessary step towards reconciling ourselves, subjects of Partition's post-amnesias, with our former lost pasts, and in moving on.

Ananya Jahanara Kabir is Professor of English Literature, King's College London, and author of Partition's Post-Amnesias, and Territory of Desire: Representing the Valley of Kashmir.

Comments