Echoes from Old Bengal

The unbelievable array of a galaxy of illustrious Indians particularly in Old Bengal was an enviable historic period that enriched generations, shaped the course of our history and directly led to the nationalist movement for independence from British colonial rule. I have been gradually compiling the life and times of some dedicated, conscientious, and civil servants, especially those belonging to the former Indian Civil Service (ICS), whose lives had been touched by the ethos of the Bengal Renaissance, and who went on to selflessly serve and leave their mark in the then East Bengal, now Bangladesh. Undoubtedly, one such eminent personality was JN Gupta, ICS, who served in Noakhali, Rangpur and Dhaka with distinction.

Jnanendra Nath Gupta was born in 1869 in colonial Bengal. His father, Ghanashyamdas Gupta, was a district judge and, therefore, he spent his childhood in various parts of Bengal and Bihar. By all accounts, he was a mischievous child, always bubbling with merriment and full of ideas for impossible escapades. He was a keen football player and kite flyer, and later added cricket to his boyhood achievement.

Jnanendra Nath studied and passed his Matric exam from Shampukur School in Calcutta. He then joined the Metropolitan College, Calcutta, of which Professor Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar (1820-1891), the illustrious scholar, was the principal. There was mutual affection between the great man and his pupil. Jnanendra did honours in three subjects – English, philosophy and history. He came through with flying colours, and did his master's degree at the prestigious Presidency College, Calcutta. He and his lifelong friend Pramatha Nath Kar alias Paltu (1864-1937) then went to Dakshineswar, near Calcutta, where they stayed for some months and met Sri Ramkrishna (1836-1886), Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902), Keshub Chandra Sen (1838-1884) and other eminent personalities of Bengal on a daily basis. Needless to say, it was a most satisfying and enriching experience in the lives of the young ones.

During this period, Jnanendra Nath edited the Bengali monthly magazine Sahitya to which the well-known intellectuals and writers of the day contributed, among them being Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), who was also his personal friend.

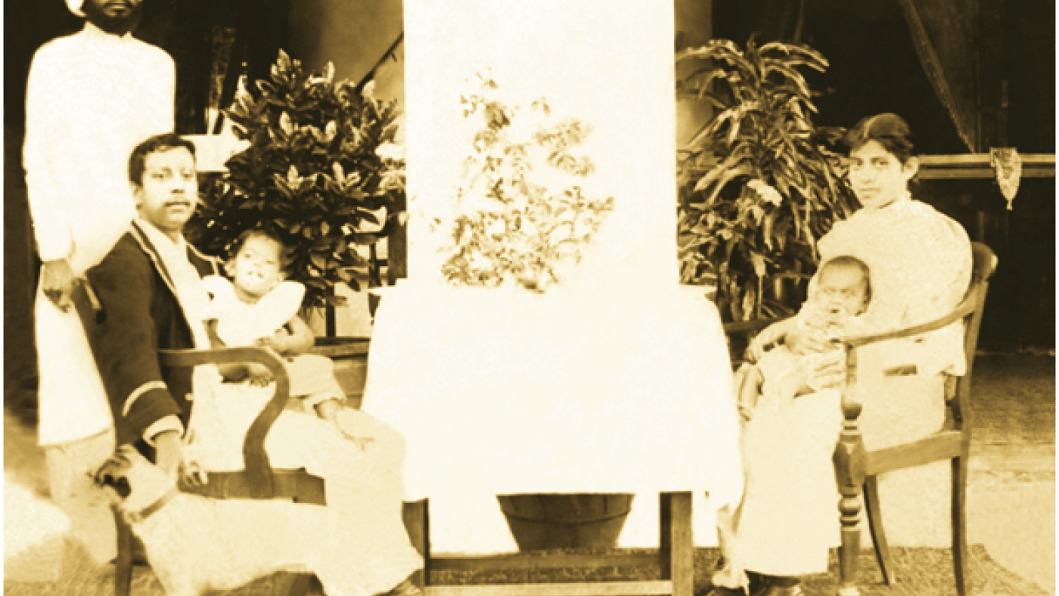

In 1891, Jnanendra Nath left for England with Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das (1870-1925) and GP Roy with whom he had been friends throughout his college days in Calcutta. He sat for the Indian Civil Service (ICS) exam in 1892 in London and passed out 2nd among those from India. In 1893, he went up to Oxford for a year. He returned early the following year to India and was married in May to Sarala, daughter of the renowned stalwart Romesh Chunder Dutt (1848-1909), the 2nd Indian ICS officer to join the elite service in 1871, after Satyendranath Tagore (1842-1923), Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore's eldest brother, who was the first Indian to join the ICS in 1863. From 1895 to 1896, Jnanendra Nath was posted in Khurda Road, Orissa, from where he often visited Cuttack where his father-in-law, RC Dutt, was posted as the Commissioner of Orissa. Incidentally, Dutt was the first Indian Commissioner to hold that post.

From Khurda, Orissa, Jnanendra Nath went to Malda, my late beloved father's ancestral hometown and while there, Lord Curzon (1899-1905), the Viceroy of India, and Sir John Woodburn (1898-1902), Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, visited the famous ruins of Gour and Pandua. Due to the sudden absence of the Commissioner and the Superintendant of Police (SP) of Malda the onerous task of making all arrangements to welcome and take care of the august visitors fell on the shoulders of young Jnanendra Nath. However, everything went so satisfactorily that he was specially invited to be present at Curzon's Great Durbar held in Delhi in 1903, a mark of great personal distinction in the heydays of the British Raj.

Before Jnanendra Nath left Malda, he arranged for a good boarding establishment for boys. He also saved the life of an innocent man. The poor Indian was sentenced to death by hanging on false evidence. But Jnanendra Nath had proof of the man's innocence. Since approaching the English Commissioner had no effect, he took the matter right up to the Viceroy and the man was saved. Such was the strength of his conviction and character.

Jnanendra Nath's passionate wish and lifelong work were for the betterment of the poor people who eked out a miserable existence from the land. Whichever district he served in, he tried his best to provide the needy with agricultural help in the form of implements, improvements in irrigation and encouragement of rotation of crops. While he was at Bankura, West Bengal, he concentrated on irrigation channels as the countryside was dry. He also rid the district of a large gang of dacoits which had been terrorising the villagers.

One morning, Jnanendra Nath heard about a dacoity and murder in an obscure village. Always an impulsive man with strong ideas of right and wrong, he was so shocked at this news, that without waiting a moment, he took a bicycle and cycled 37 miles to the village. Having been given details of the crimes and names of the victims and witnesses, he cycled all the way back to Bankura.

At this period in time, Jnanendra Nath made a point of teaching the villagers to take interest in their Union Boards and to decide questions concerning their own roads, ghats (quays), land and schools. He loved the outdoor life his work entailed. He toured constantly in the winter months, both riding and cycling, and liked nothing better than pitching his tent in a small village and acquainting himself with the names, joys, troubles and habits of the villagers.

Jnanendra Nath served in East Bengal (now Bangladesh) in Noakhali as the district magistrate in 1908. In 1914, he became the collector at Rangpur, and served there for nearly four years. The years spent at Rangpur, he told his family, were his happiest. His colleagues were singularly sympathetic to his aims and high ideals and they worked together in complete harmony. His close friend SC Mallick was the district judge there. Both he and his wife toured extensively, and he established many girls' schools in the villages, which the villagers fondly named all after his wife, Sarala. In 1916, he founded the famous Carmichael College in Rangpur—the first such premier educational institution in the district and in the northern region of East Bengal. The college has since become an architectural landmark. For this valuable work towards the promotion of higher education he should be remembered not only by the people of Rangpur, but also that of Bangladesh. In 1919, he became the Commissioner of Dhaka.

In 1918, Lord Satyendra Prasanno Sinha (1863-1928) went to England to join the War Cabinet. He asked Jnanendra Nath to accompany him as his secretary, which he gladly did.

In 1921, Jnanendra Nath went to Geneva with Sir Atul Chatterjee (1874-1955), another old and dear friend of his, as delegates of the League of Nations – Labor Branch. When he returned, Sir Surendranath Banerjee (1848-1925) was Minister of Local Self-Government in Bengal, and he insisted that Jnanendra Nath become chairman of the corporation. Sadly, by this time, he was suffering from neurasthenia and pleaded that he would not be able to give his best to the new post, but Sir Banerjee had made up his mind that there would be an Indian chairman, and that Jnanendra Nath was best suited for it. Jnanendra took up the work in earnest as chairman. Even while his work kept him in Calcutta, Jnanendra Nath worked tirelessly on Bengal's agricultural problems. His little handbook, Foundations of National Progress, Agriculture in West Bengal, is still regarded as a textbook. Even after he retired and had settled in Barrackpore, north Calcutta, he devoted his mornings to the organisation and work of a Demonstration Farm near his house, where various fruits, vegetables and food grains were grown and regularly sold to the Calcutta markets. In time, the farm became self-sufficient, and new departments were opened where young men were taught woodwork, carpentry and the making of steel gadgets. When the work became too heavy for him, Shyama Prasad Mookerjee (1901-1953) took over the farm for the Calcutta University. While he was in charge, the farm had many visitors, one of the keenest being Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore himself who was also extremely interested in Bengal's agriculture.

Although Jnanendra Nath belonged to the coveted and elite ICS, he was by no means the imperialistic type so popular with cartoonists then. Some noteworthy episodes in his life illustrate this. When he was Commissioner of Burdwan, West Bengal, he did not like the overbearing behaviour of two English ICS officers. They were junior to him and he was quite frank with them about his opinion. The matter went up to the Home Member who tried to hush things up. But Jnanendra Nath would have none of it and was adamant. The matter finally went to the Public Services Commission. Jnanendra Nath gave evidence, and the whole incident was published in the nationalist newspapers. The two Englishmen were reprimanded.

When Jnanendra Nath was a member of the Bengal Legislative Council, he made it a point not to back the government on the issues of Bengal's revenue being appropriated by the centre and the devilish Communal Award. This did not make him too popular with the Indian quislings and communalists who believed in the omnipresence of the British. He was not a friend of Sir John Anderson (1932-1937), the British Governor of Bengal, and their views on a number of things of import were diametrically opposite. Jnanendra Nath always stuck to his beliefs whenever he was convinced that they were correct and in the best interest of India and its people.

Jnanendra Nath was a member of the Board of Revenue when he retired in 1928. He and his wife Sarala travelled every year and visited their children and grandchildren all over India. He was never happier than in the winters when his whole family, and as many relatives and friends as could come, stayed with him and saw the New Year in. He was manager of the princely Indian state of Dumaron, Bihar, for two years and enjoyed the outdoor life there. He rode every day and there was plenty of shooting. His house was always full of guests, gaiety and laughter. After leaving Dumaraon, he settled in Barrackpore. He devoted himself to his beautiful garden and the Demonstration Farm. Here too, he always had his friends and relatives staying with him, and his Sunday tennis parties were well-known. At this time he also contributed to magazines and newspapers regularly. He had always loved reading and now he had plenty of opportunity to indulge in his love for history and philosophy.

Jnanendra Nath Gupta, ICS, a compassionate, conscientious and distinguished soul, died of old age ailments in 1946. He was 77 years old, and was greatly mourned by all those who had the rare privilege of knowing him.

The writer is Founder, Bangladesh Forum for Heritage Studies.

Comments