Raghu Rai: The Man Behind the Lens

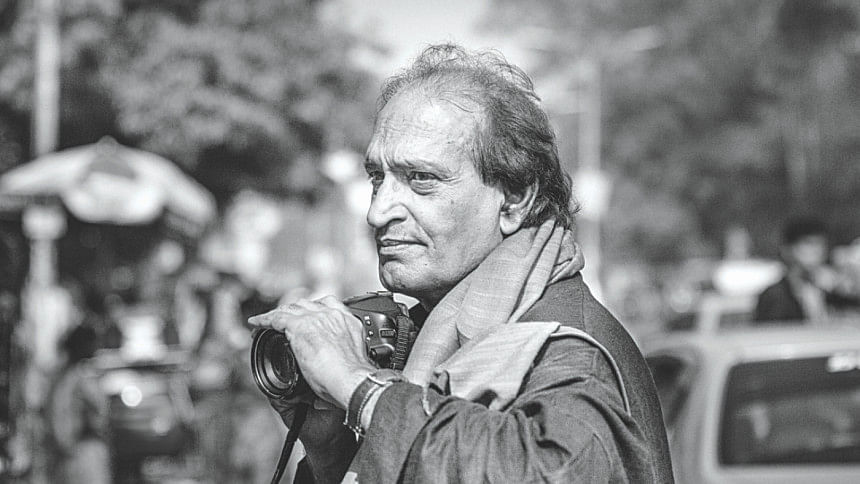

Indian photojournalist and member of the prestigious Magnum Photos, Raghu Rai, is better-known to Bangladeshis for the photos he took during our Liberation War in 1971. Rai, who has been awarded the Friends of Liberation War Honour, recently visited Bangladesh on account of Drik's Chobi Mela X. This week's In Focus publishes an interview of Rai with Ananta Yusuf, Producer, Star Live, The Daily Star.

How did your journey in photography begin?

I qualified as a civil engineer, because that was what my father wanted me to pursue. I worked with the government for a year-and-a-half and I got really bored with it—I didn't know what to do. So I went to stay with my elder brother S Paul, who was a famous Indian photographer. He was eleven years older than me. Unfortunately, he passed away last year, but he lived a good life. When I went to stay with him, I had no idea what I wanted to do with myself.

During my stay with him, there were many photographers who came to visit him. They discussed pictures, lenses, ideas—I used to wonder what a crazy lot they were. One day, I heard that one of S Paul's very good friends was going to his village to take photos. I really liked him, so I said: "Bhaisab [S Paul], I will also go with him. Can I?" I thought it would be like a holiday. I don't know what happened to me while leaving; when leaving, I asked S Paul for a camera so that I could take some photos as well. He loaded a film in a small camera, gave it to me, and explained to me a bit about exposure. The first picture that I took was of a baby donkey in the village. I saw a donkey foal in a field, and when I tried to get closer to the animal, it started running. After a few minutes, it became tired and just stood there. So I got closer and took the shot. It was taken in a soft light and the background was totally blurry.

From 1965 to 1971/72, The Times newspaper of London used to publish a half-page photo every weekend. These had to be funny, strange or interesting—something unique. My brother used to send in his photos. When he sent in the photo I had taken, they published it. I was may be 24 or so at that time. They published the photo with my name, and the money they paid for it was enough for me for a month. Everybody was saying that this was a big deal that my photo had been printed, and I thought "why don't I try my hand at this."

At that time I'm sure photography was not a very popular career choice. How did your parents react?

My father was really upset because I was a qualified civil engineer. My elder brother was also a photographer and my father didn't like it. When somebody used to ask him "how many sons do you have?", he would say, "I have four. Two have gone photographers" [akin to "two have gone mad"].

You started your career when the likes of Kishor Parekh, S Paul, Raghubir Singh were already established. How was the interaction at the time between the young and established photographers?

Kishor and Paul were ten or eleven years older to me. They were already well-known by that time. Kishor Parekh was the chief photographer at Hindustan Times. Paul was chief photographer at Express. I joined The Statesman, and in one year I had become the chief photographer. The three of us were very good friends. When I used to see them on assignments, I used to say "chhorunga nehi" [I will not let you go easy]. With two giants around me, I used to work very hard. In situations like this, you either get sandwiched by the giants and crushed, or you pop up. I think the latter happened with me.

It was a time dominated by magazines. Most photographers either worked for newspapers or magazines. The subjects were also limited to photos of politicians, celebrities or landscapes.

You are right. This was a very boring pictorial time in our part of the world: taking pictures of pretty landscapes, old men and wrinkled faces, pretty girls, a little child, tight close-ups. And then Paul and Kishor, being in photojournalism, had to deal with daily realities, and it became a different ball game. We did not indulge in the kind of photography that was popular. They would, out of daily life or political situations, capture something unique and rare.

How did you get the assignment to cover Bangladesh's Liberation War in 1971?

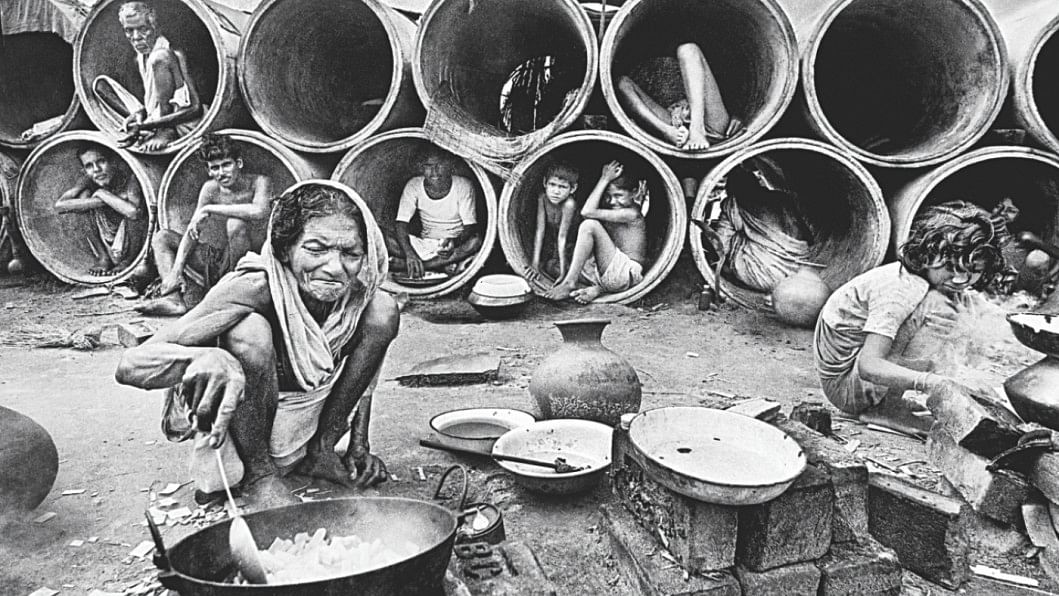

At the time I was the chief photographer of The Statesman. So you see, whenever there was an important assignment, it was my duty to assign. I was in Delhi, but the headquarter was in Calcutta. When the refugees started coming in, they called me in to Calcutta and sent a reporter with me to the border areas. We went into Jessore also when the Pakistan Army had withdrawn from there. I photographed the Muktibahini—poor men holding rifles. Nobody was really ready for it you know—the Pakistanis didn't leave anything for the Bangladeshis to fight back with. I took pictures of refugees coming down towards us. I took pictures of Bangladeshis travelling by buses and rickshaws, carrying their kids, of broken bridges and things like that. When they started concentrating in India, I photographed the camps.

Most of your photos of the war are of either women or children. Why is that?

Women suffer a lot more than men. Women want to take care of everything. Children suffer the most because they are the tender and gentle. Men were disturbed, yes, but somehow the women aroused more emotions and more pain for me. You know, the Bhopal Gas Tragedy—the photo of the child had become an iconic photograph. Children can touch everybody's hearts.

You lost all the negatives from 1971; how did that happen and how did you eventually get them back?

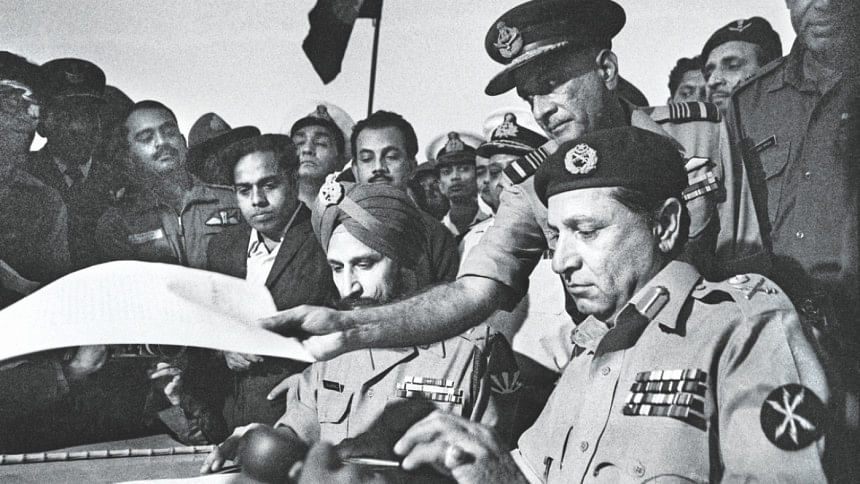

In 1977, when I left The Statesman, I picked up the negatives. But, you know in newspapers, they carry one or two pictures each day, at most three. But the bulk of the work was never published. So when I left The Statesman I took the negatives with me. I kept them in a bundle in my office. After a few years, I shifted my office to another place. These boxes had all sorts of packets of negatives and other things in them. But somehow, after more than 35 years I could not find them at all. They were hidden somewhere in some box.

When I started to digitise my works, I started pulling out everything in the boxes. After 35 years. I see this big bundle of negatives, taken during the surrender by Lieutenant-General Niazi.

You met Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris during an exhibition and he was utterly amazed by your work. Can you please share that experience?

I had taken some pictures of Bangladeshi refugees, coming to India, which were very intense. Twenty photos of Bangladesh refugees and fifty of my creative works were exhibited at a gallery in Del Piero in 1972. The exhibition was to open at 6 pm and at quarter to six I saw somebody carrying a Leica camera and looking at each picture very carefully. I looked at him and though that it must be Bresson. I watched, and then went closer, and finally I asked him. He replied that he was indeed Bresson. He asked me if I was the photographer. He said to me: "Let me see, then I'll come to you." Afterwards he said "very good". Then he rang up his wife Martine Franck and told her that he had met a very good Indian photographer, and would like to invite him home.

So I got invited to their home for dinner—it was an amazing experience. When I went back to India, I received a letter from Magnum Paris that Mr Bresson has nominated me as a member. I was taken aback; I said, "Oh my god, Bresson! These people! I don't think I can work with such people. How can I be, a little boy, be working with them." I ended up not replying in 1972. I was still working with The Statesman, which was at that time a very important paper.

In 1977, I decided to leave the newspaper. As I was packing up things important to me and negatives, this letter showed up again. Since I was leaving the newspaper, I sent a telex message to the director of Magnum, Jimmy Fox, in Paris. I told him that I was leaving my paper and asked if the offer was still open. He replied that it was. That this is how I joined Magnum. You know people do all kinds of things to try to become a Magnum photographer. I never had to do it.

Was there any particular incident with Bresson that you still cherish? And did his work influence yours?

Once, my wife and I were going to the Arles festival [the Rencontres d'Arles]. Learning of this, he invited me to his farm which was nearby. He sent his car to us at the festival. His farm had acres and acres of land. I asked why he was not growing anything since it was all an empty landscape. "You know, this is the problem in your part of the world and here. There you don't have enough food but here my government is paying me to not grow anything because they cannot manage so much food."

As for influence, no. I have admired him as a human being and as a photographer. But when I take photos, nobody exists for me. It's my direct connection with the situations.

Going through your photos of Indira Gandhi I perceive an angry lady surrounded by many men. On the other hand, you portray Mother Teresa in a most soft and serene way. Did you intentionally portray these two women in such different ways?

Never. I have no agenda. I don't believe in agenda. I believe in capturing the truth and the sense of a situation. If that situation has its own reflections, good, bad, peaceful, angry or whatever, is another matter.

Looking back at your journey as a photographer, how do you evaluate it?

Well, photography is my dharma. Photography has taught me many things about life, about nature, about God, about reality—so my journey has been very fulfilling. I am an explorer. And with divine grace. I am still growing.

All photos by Raghu Rai have been used with permission of the photographer. Copyright: Raghu Rai/Magnum Photos

Comments