Partition 1947: The Many Migrations of Siraj-ul Huq

Seventy-six years after the Partition of the Indian subcontinent, we are still a long way from understanding the complex ways in which this event affected the everyday lives of people and communities then, and how it still continues to shape our collective consciousness, politics and ways of being. This series, featuring scholars of partition studies from across the subcontinent is an attempt at exploring the complexities and contradictions of the momentous event that forever changed the contours of this region. This article looks into one man's journey through the events of 1947 and 1971, and his experience of being a refugee and then a stateless person.

In the Jehanabad district of Bihar, India, there is a town named Kako. Around 4km away from this town, in a small village named Firozi, Siraj-ul Huq was born sometime in early 1938. He is not someone "important" – not one of those "big men" whom we read about in our history books. I, nonetheless, choose to write about him.

There can be multiple ways to justify this choice. To me, the two most important reasons are: a) the life he lived and the roads he traversed reveal the arbitrariness of national borders in South Asia; and b) his astounding resilience during times of communal riots, civil wars, and economic uncertainties was inspiring.

Let me begin with a disclaimer. I have never met Siraj-ul or any of his family members personally. As a recipient of a research grant, I had a month-long access to the 1947 Partition Archive, where I chanced upon a long video interview of Siraj-ul Huq. The interview was conducted by Sharf Alam at Siraj-ul's Karachi residence on January 26, 2019.

Though an octogenarian by then, Siraj-ul had unusually vivid memories of his younger days spent in Bihar, Calcutta, Dacca, and Karachi. His travels across the subcontinent, the humorous anecdotes that he shared, his experiences of the big events like the Calcutta Killings (1946), Partition (1947), and the Liberation War (1971) made his interview particularly fascinating.

More importantly, as I listened to him, I realised how the repercussions of Partition were felt by many ordinary people of the subcontinent, way after 1947, and how they negotiated with them in several ways.

Instead of providing an account of Siraj-ul's entire life, I will focus on two phases – his life as a refugee boy in Dacca in the 1950s, and his journey from Dacca to Karachi after the Liberation War – as they elaborate the points that I wish to make most succinctly.

From Siraj-ul Huq to Muhammad Muneer Uddin: Life in Dacca

Towards the end of 1949 or in the very beginning of 1950, Siraj-ul came to Dacca with his mother. His father had been working in Calcutta for many years. After spending the first few years of his life in Firozi, Siraj-ul joined his father in Calcutta sometime before the notorious Calcutta Killings. He had vivid memories of the ferocity of the communal riots that shook Calcutta and the adjacent areas in August 1946. As Calcutta became an Indian city after the Partition of British India, his father became anxious about their safety and well-being. Many of their coreligionists were contemplating migration to East Pakistan; so was his father.

Finally, towards the end of 1949, when once again the communal situation deteriorated in the city, his father decided to send Siraj-ul to East Pakistan with a group of Firoziwalas (Muslims who were originally from Firozi). Siraj-ul and his mother, thus, embarked on their hijrat – a term Siraj-ul often used in his interview to depict his migrations.

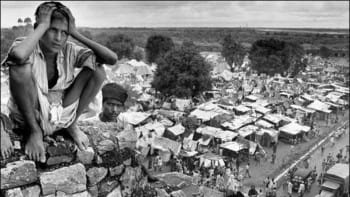

After reaching Dacca, neither his mother nor Siraj-ul knew what their next step should be. Siraj-ul was a kid anyway, still enrolled in the fifth standard of a Calcutta school. His mother had always followed her husband in everything that she did. Suddenly they were on their own in a new city where they knew no one. Siraj-ul went out to look for a "Calcutta-type house" in the slum near the railway station. But soon he realised that there was an acute housing scarcity in Dacca. The Hindus were fleeing as there were riots in Dacca as well. But the houses that they left behind were promptly occupied by the Muslim refugees. Siraj-ul could not manage to grab a property amid this chaos.

Luckily for them, an empathetic railway porter came to their help. He told them to wait at the station itself as a "refugee" train was expected to reach Dacca shortly. The train was bringing hundreds of Muslims from Calcutta who, like them, were coming to Dacca because of the riots. The government would surely make some arrangements for them, the porter mentioned and advised Siraj-ul and his mother to simply join the group to avail government facilities. Siraj-ul and his mother followed the advice. And indeed, with other refugees, they were soon taken to a large mansion, where the East Pakistan government was running a refugee camp.

This mansion – temporarily requisitioned by the government of East Pakistan at that time – was called Shankhanidhi Lodge, and it was built by a rich Hindu entrepreneur of Dacca named Lalmohan Saha in 1921. Siraj-ul remembered the grandeur of the house, the ornate pillars and intricate designs.

In this mansion, like Siraj-ul and his mother, many other refugees were housed. Their names were registered and they started receiving free food. At this lodge, his mother befriended another refugee woman. She advised Siraj-ul's mother to enrol the name of a baby in the government register. If a family had a baby, they were entitled to a daily quota of milk. Siraj-ul's mother did so and received an identity card for her four-year-old fictitious baby daughter, Munni. Amid the crowd and the chaos, the men looking after the refugees at Shankhanidhi Lodge had very little time to verify individual applications. The refugees took advantage of the situation to get a little more food or some other minor privileges. With three identity cards, Siraj and his mother began to receive rice, daal, vegetables, and meat for lunch and dinner, and milk and muri-murki (puffed rice) for breakfast. Though the food was free, the long queue for it was humiliating. For the first time in his life, Siraj-ul and his mother had to stand in a line to get food.

The mother-son duo lived in Shankhanidhi Lodge for around two months. While they were there, one day they received a letter from Siraj-ul's father – who was still in Calcutta – about his plans to visit them shortly. While this was good news for many obvious reasons, it generated some immediate anxieties for them. The lodge was full by then and the government was no longer accommodating any new refugees there. The refugee residents of Shankhanidhi Lodge were not allowed to bring in guests or visitors either. Anyone entering or leaving the lodge had to show their identity cards at the gate. How would his father enter the lodge and stay with them, they wondered.

Then, Siraj-ul hatched a plan.

They had the card of four-year-old Munni, which came to their help. Siraj-ul put a "1" before the "4" and added "ruddin" after the name Munni. And it became the identity card of 14-year-old boy named Munniruddin (Muneer Uddin). He also scribbled on his own identity card that had his name (Siraj-ul Huq) and his age (14 years). He kept the name the same but changed the age to 40. This became the identity card that his father would use, and he himself started using the card with the name Munniruddin on it. Since this identity card was used for school admission and to avail refugee scholarship, Muneer became Siraj-ul's permanent name.

Creating the fake identity card for a milk allowance or fudging the documents to ensure the entry of another individual to the rehabilitation centre are fantastic examples of tactics that refugees adopted to make their lives a little better amid all the hardships they faced. Such tactics reflected their resilience, agency, and enterprise.

While studying the consequences of Partition in South Asia, we often become overwhelmed by the individual narratives of sufferings and loss. Paying attention to such narratives is important to understand the magnitude of the crisis that was unleashed with Partition. One, however, needs to remember the stories of resilience and enterprises as well. Such stories reveal how, despite all odds and with very limited means, the Partition survivors negotiated with the crisis to the best of their abilities.

Muneer, aka Siraj-ul, would continue to live in Dacca for several years. He would finish his matriculation from a city school in 1954 and then he would travel to Karachi, where he had some relatives, in search of a job. The job would again bring him to Dacca at a time when the politics of the city and of the province had changed drastically. The battlelines had been redrawn and it was the Bihari-Bangalee antagonism that had replaced the Hindu-Muslim strife as the most definitive feature of the politics of the province.

Fleeing Dacca via Calcutta, Kathmandu, and Rangoon

Muneer came to Dacca for the second time around 1970. He was now a married man with three children and a stable job at Pakistan Airlines. People in Karachi had warned him against going to Dacca, as the city was no longer welcoming to Bihari Muslims. Muneer did not listen to them. Afterall, he knew Dacca, had spent five adolescent years there, and still had a few friends and a handful of relatives in and around the city.

But soon after they settled down, the situation worsened. His father-in-law, sitting in Karachi, became restless about their well-being. But Muneer was not yet ready to leave. He had seen troubled cities before. The memories of Calcutta of 1946 were still fresh. He was not intimidated as yet. Moreover, he was shaped by the Partition and communal politics. He could understand Hindu-Muslim antagonism, but he was yet to grasp the meanings of hostilities within the Muslim community in East Pakistan.

A colleague in his office in Dacca warned Muneer, though. He used to come from a small village every day and had to change boats thrice to reach Dacca. While coming to Dacca, he saw dead bodies of Bangalee men floating on the river. Though he himself was an Urdu-speaking pukka (solid) Maulavi, he told Muneer that Pakistan would soon collapse because it was cursed by the Bangalees. No nation could survive if it oppressed its own people. The ominous predictions of his colleague, the anxious phone calls of his in-laws from Karachi, and the deteriorating situation in Dacca forced Muneer to send his family back to West Pakistan. He, however, stayed on.

He was a government employee and leaving Dacca would mean leaving the job. He only left Dacca after the war ended and East Pakistan became Bangladesh – a new sovereign nation-state.

Muneer's journey from Dacca to Karachi was a risky adventure. His first stop was Calcutta, a city he remembered fairly well. He stayed for a few days at a cheap hotel in Zakaria Street, met with a few relatives who still lived in the city, and headed for Firozi for one last time. He wanted to see his ancestral home before leaving for Karachi. Perhaps his intuition told him that he would not be back in India anytime soon.

In Firozi, he met some of his relatives who had stayed put despite Partition and riots. Muneer's next destination was Kathmandu.

Many Bihari Muslims migrating to Pakistan from Bangladesh did so via Nepal – a country that had remained outside the Indo-Pakistan conflicts as much as it could. It had a fully staffed and operational Pakistan embassy where Muneer reported. He needed a seat on a Karachi-bound flight. He had little money with him; but he was a government employee fleeing an enemy country. The Pakistan Embassy, after checking his credentials, promised to make arrangements for his travel. But it would take some time, they said. There was a mad rush in all Karachi-bound flights. Muneer, therefore, spent a few days in Kathmandu, stayed in a cheap hotel room, and ate at the only Muslim hotel he could locate.

Finally, the tickets came. He was to leave for Karachi on a flight operated by the Japan Airlines, that would fly via Rangoon.

Muneer, almost penniless by then, boarded the flight from Kathmandu. The flight, he learnt, would stop for an entire day in Rangoon. He knew that the grave of the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was in Rangoon. It was an opportunity to visit the grave.

Was this visit something more than a touristy curiosity? Perhaps, yes.

Visiting the grave of the last Muslim ruler of the subcontinent, no matter how weak he was, at a time when an Islamic state had fallen apart, perhaps reflected the crisis in the emotional world of a Muslim man who had sympathised with the Muslim League politics, served Pakistan, and had faith in its founding ideals.

Amid this gloom, the local Muslims of Rangoon offered him some respite. They were visiting the airport daily to meet the Muhajirs migrating from Bangladesh to Karachi. They went there to show solidarity and support, to offer them food, paan (betel leaf), and tea, and to show them around if they had a long stopover. Like Muneer, the Muslims of Rangoon – at least some of them – were devastated with the disintegration of Pakistan, a unique nation-state that had promised to champion the needs of the followers of Islam in the subcontinent.

After a long journey across several countries of South Asia, Muneer reached Karachi. Tired but safe, he met his family, joined the Karachi office of the Pakistan Airlines, and his life gradually limped back to normal.

In many ways, he was luckier than some of his coreligionists who had travelled to East Pakistan from Bihar. Not everyone could leave like him, even if they wanted to. After the war was over, despite several promises, Pakistan refused to take back many of them. They still live in camps as "stranded Pakistanis," awaiting citizenship rights in Bangladesh or resettlement in Pakistan. If Partition had turned them into refugees, the Liberation War made them stateless. Even after 75 years since Partition, home remains elusive to them.

(The 1947 Partition Archive is a crowd-sourced, community-based archive of more than 10,000 interviews of Partition survivors.)

Dr Anwesha Sengupta is assistant professor at the Institute of Development Studies Kolkata (IDSK) in West Bengal, India.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments