Tareque and Munier: You are always with us

When I think of Tareque and Mishuk, I carry in my mind's eye the image of the two of them bent over a camera monitor reviewing the day's footage or seated together high on a crane surveying the next scene to be shot. They are out there somewhere, the images seem to say to me, at some elysian shooting spot continuing their creative partnership into eternity. They relished their work, both of them driven by the sheer love of cinema. I cannot imagine them simply enjoying a moment without purpose or direction. And that was what drew them to one another also. Curiosity and the drive to create, untarnished by any narrow agenda or narcissism.

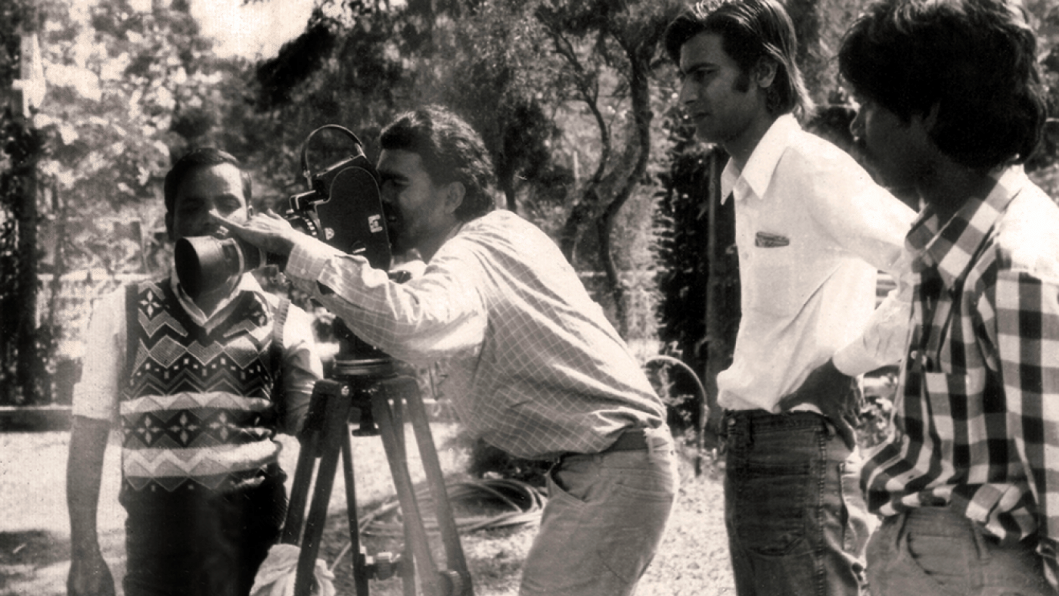

They had been friends at Dhaka University, and had attended Alamgir Kabir's legendary film appreciation course at the then fledgling Bangladesh Film Archives. Kabir bhai was a towering figure for both, with his charisma and fearlessness. If the means of production were lacking, Kabir bhai would say, create your own means. And Tareque and Mishuk followed that call, when without money or much knowledge of filmmaking they embarked on what eventually became a 7-year quest to complete the documentary on the painter S M Sultan. For both of them, the journey was as important as the goal. It was not only a journey of filmmaking; it was also a journey of discovery of the beauty and depth of life. Sultan was an elusive and often capricious subject, at a moment's notice cancelling a carefully planned shoot to drag the two aspiring creators off to a Baul mela or to meet the famed folk musician Bijoy Sarkar. They slept on the floor of Sultan's crumbling former zamindar palace in the jungles of Jessore, and listened spellbound to Sultan's meandering monologues on art and the peasantry. Their film materials were scant anyway—usually they were only able to manage a few hundred feet of 16mm film stock at a time, a matter of 10-15 minutes of footage. Then months would slip by when they lacked the resources or the access to buy more material. But there was no limit to their imaginations, and countless hours unspooled between them in talk of the scenes they would shoot—scenes of Sultan walking through the mist in long dark robes, or floating down a river on a raft while painting the muscular figures of peasants tilling the soil.

"They slept on the floor of Sultan's crumbling former zamindar palace in the jungles of Jessore, and listened spellbound to Sultan's meandering monologues on art and the peasantry. Their film materials were scant anyway—usually they were only able to manage a few hundred feet of 16mm film stock at a time, a matter of 10-15 minutes of footage.

These were the stories I heard from Tareque when I first met him, some five years into the project, in the fall of 1987. By then most of the shooting was complete, or rather they'd exhausted their resources and drive to continue the endless odyssey of capturing Sultan on film. The film was then in post-production at DFP, and that is where I joined in on the project—my introduction to the filmmaking process. One day during that period, Tareque took me on a rickshaw through the winding tree-shaded lanes of Dhaka University, to the faculty quarters on Fuller Road where Mishuk lived with his widowed mother. Mishuk by that time had a full time job at the National Museum, so he could no longer go for a shoot at a moment's notice. But we talked about the patch shooting that remained, the progress on the edit, and the latest cameras. I could immediately sense the easy camaraderie and deep sense of mutual respect that bound them as friends and colleagues. As we chatted about the technicalities of doing in-camera dissolves and fades on a 16mm Bolex camera, I also felt drawn into the circle of fascination for all things cinematic and technical. I understood the glint in their eyes as they contemplated bypassing the need for a lab to create such effects—in any case, such facilities were painfully absent in Bangladesh. It was the lure of a challenge, of creating the means where no means existed before.

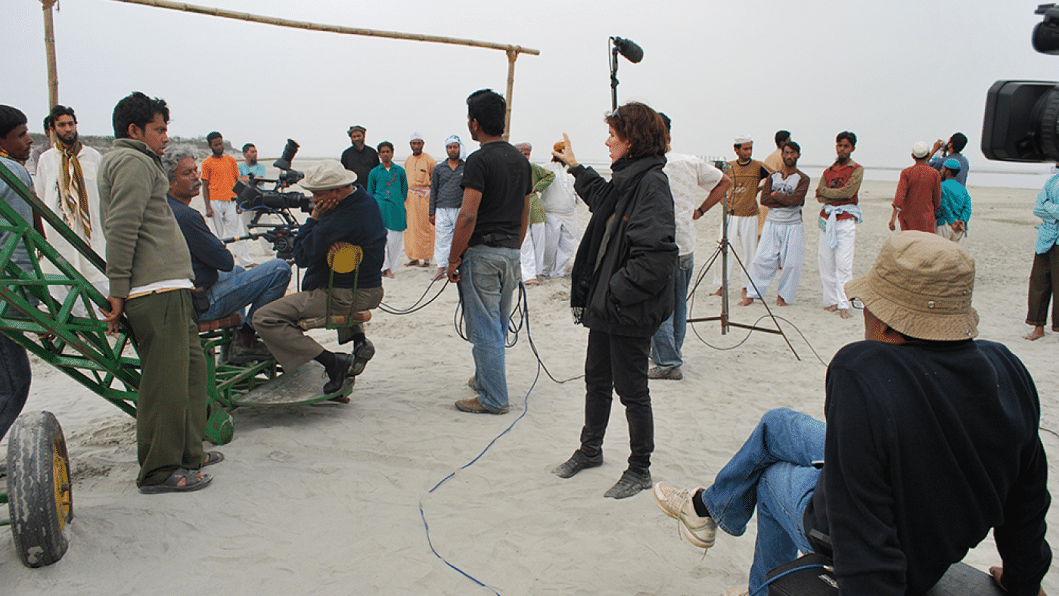

This meeting was the beginning of a three-way partnership and a friendship that lasted for the next twenty-four years. Although Muktir Gaan (Song of Freedom) was primarily a compilation film, Mishuk and Tareque worked together to shoot a re-enactment scene of a night battle from the war, which they sent to me, ten thousand miles away in New York, to do the final editing and sound. With Muktir Kotha (Words of Freedom), made later in the 1990s, I became an integral part of the Tareque-Mishuk team and was able to appreciate up close the creative synergy that existed between them. We travelled together to remote parts of the country to capture the stories of ordinary people who'd experienced the war. In the village of Kodalia in Faridpur, where the Pakistan Army in collusion with local collaborators had massacred some twenty women and children, Tareque and Mishuk worked with a combination of tact and precision to draw the story out of the people we interviewed. Tareque was a master of prompting a person to bare their soul, while Mishuk understood instinctively when a close up was required or how to improvise in unexpected situations. Another particularly challenging part of the shoot was the multi-camera scene of freedom fighter-singer Shah Bangali's performance of Muktijuddher Sangram Charbo Na in a village in Narshingdi. In this scene, we had to create the impression of spontaneity when the singer offers to come up to the projection stage after a film show to perform. In fact, the entire scene was elaborately planned out, with Mishuk, Tareque and me working out a diagram of camera angles and character movements as if in a scripted feature film. Tareque and Mishuk revelled in this approach to documentary, where real stories with real people were blended with fictional techniques.

After Muktir Kotha, there was a gap of several years during which time Mishuk was tied up with his work at Ekushey Television, and later with an online news channel in Canada. Thus, he was unable to join the team of Matir Moina (The Clay Bird), which we instead filmed with the very talented Bombay-based cameraman Sudheer Palsane. But we never stopped dreaming of working together again with Mishuk as a team. We began to reconnect in 2005, when Mishuk did some patch shooting for us on Ontorjatra (The Homeland) during one of his visits to Dhaka. Mishuk was still based in Toronto but told us he was interested to work on some bigger projects and could arrange the time off from his office with enough notice. Over the next couple of years, we worked on a series of shorter projects while discussing various feature film ideas, notably Kagojer Phul (The Paper Flower) and Runway.

Naroshundor (The Barbershop) was one of the smaller projects that allowed us to experiment with the application of documentary techniques to fiction film—the flip side of our earlier "fictionalised documentary" approach. As with Matir Moina, we worked with a largely nonprofessional cast, including actual barbers from the Bihari community. By using multiple cameras and a fluid shooting style, we tried to create a sense of immediacy and tension. The biggest challenge was managing the reflections of multiple mirrors in the very confined space of the barbershop. On the first day of the shoot, Mishuk showed up dressed completely in black. The rest was orchestrated with careful rehearsal, adjustable mirrors, and lots of takes!

We expanded our collaboration on fiction film with Runway. By this time the mutual respect that underpinned Tareque and Mishuk's working partnership had evolved into an almost unspoken understanding of what was needed to capture a particular scene. After seeing the location on the airport runway, Mishuk simply said "telephoto lens", and Tareque nodded. When Mishuk went back to Canada to search for the right equipment package, he tracked down a pristine second-hand Nikon 200mm lens. This lens would be used to create the iconic image of Ruhul walking between the runway guide lights as a massive 747 descended behind him. I remember the excitement of having successfully timed and captured that shot, and the elation we felt at having pooled and coordinated our respective talents to bring about that magic moment.

Tareque and Mishuk's teamwork was constantly evolving as they continued to learn and experiment, and there was a sense of endless possibility between them. Somehow, I fit into that configuration, and we made a triad. With them gone now, I feel stripped down to my own bare essentials, forced to re-imagine my creative path without the igniting power of that charmed circle. But still the team is within me. I feel it, when I pick up my camera to "cover" a documentary scene, and remember what Mishuk taught me about visualising the edit before the scene has been shot. He taught me without words—what I learned was through watching him as he worked and then editing what he'd shot. And Tareque too, of course; a thousand wisdoms ring in my ears at every step, not only in film but also in life. For every life they touched, they were like an igniting fire, setting the dreams of those around them alight. And that light will continue to guide us through dark times, as long as their memory lives on.

We must learn to focus not on what we've lost, but what we've gained from having them with us as long as we did. Their lasting legacy is a model of creative vision melded with commitment to nation and the new generation. They were the epitome of thinking "outside the box", beyond narrow politically and socially prescribed categories. Theirs was a model of total dedication to work, for the pure joy of creation. And then of course the films and images they left us—those will be with us forever.

Catherine Masud is a filmmaker and an educator.

Comments