S M Sultan: The vision of a coming society

Sultan, a painter, visionary and a subaltern guru, apparently emerged out of the social "utopia" that surfaced during Bangladesh's liberation war—one that animated the masses, as opposed to the narrative of the emergent ruling elite, where this dream of a coming community later collapsed into mere words or a set of symbolic gestures. For about a decade or so following the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, what now seems Sultan's most fertile phase, a re-envisioning of the community has taken place through a utopian "communistic vision". And this has given rise to myriad imageries of a vigorous peasant population set against the rural landscape—signature images through which Sultan invoked the power of the people and we, as spectators, are forever destined to remember him.

In an interview now widely circulated in social media, Sultan, aka Laal Miah, once spoke about how the liberation war made him recast his position vis-a-vis the idea of social transformation. The promise of a futurity that requires a comprehensive rethinking of the society and subjecthood as well as their interrelation served as the basis for this change of heart. The works that sprang out of this frame of mind still retain the emotional energy the artist initially invested into them to unsettle the conventional frame of "class" and "ownership". These works flowed into a number of streams, including the one in which Sultan captured the quotidian life of villagers amidst a lush natural setting. In another type, the peasants are depicted as insurgents battling for the land that rightfully belongs to them.

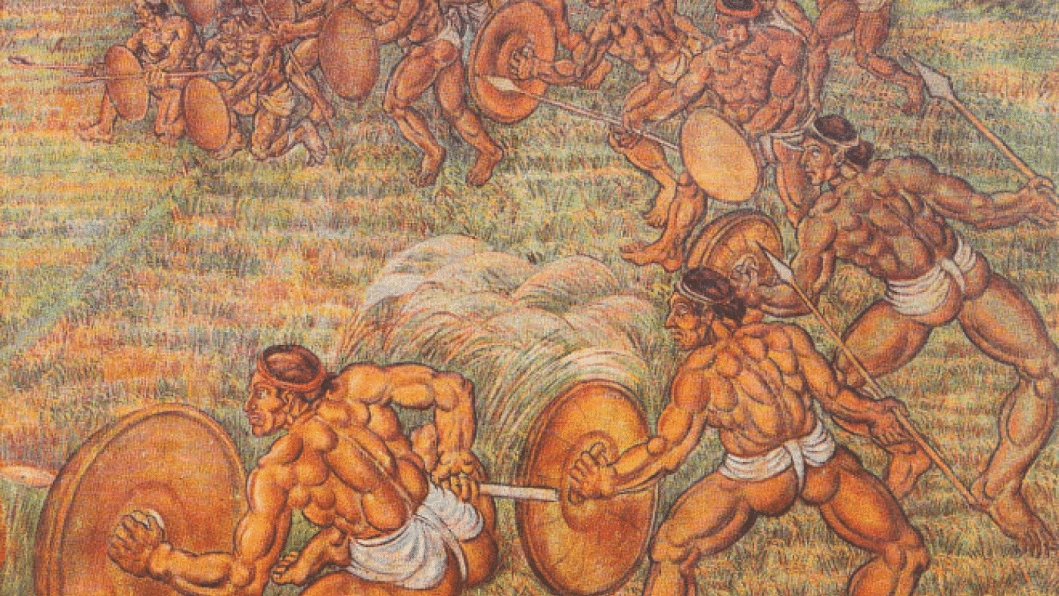

His was an enterprise involving the emergence of a new agrarian society. So in his landscape peopled by peasants, Sultan inserted the issue of "ownership", about which Burhanuddin Khan Jahangir dedicates a few lucidly written passages in his book titled Deshojo Adhunikota: Sultan-er Kaaj (lit. Indigenous Modernity: Sultan's Work) to outline the "radical seeing" the pioneer modernist has given rise to. If the depiction of the quotidian lives were a way for him to make visible the exuberance of nature and human bodies, in some of the large-scale works, his artistic conceit is suitably employed to produce a chiaroscuro-laden, dream-like imagery where his muscle-bound women take centre stage. In the scenes of rebellion, where the peasants rise to reclaim the land they till, overturning the traditional "feudal" relations based on exploitation, male figures are seen in combat manoeuvres forming an invincible defence confidently wielding swords and spears. Challenging the framework of the conventional social relation through which the landowning gentry exploited the peasants for their own end, these works are a way to symbolically invoke the potency of a people rather than re-enactment of an actual battle scene. That these images of epic quality, always, as a rule, avoid the portrayal of the enemy, is a reaffirmation of Sultan's singular emphasis—the potentiality of the resistant bodies.

"He chose to settle down in Narail, his home village, not to seek refuge in the bucolic distance, but to lend voice to the subaltern and to "talk back to the centre", vigilantly abrogating the colonial legacies that burden us to date.

The urge to unveil the utopic vision, where bodies resist the status quo to re-configure the social realm left a shape-shifting impact—both metaphorically and literally. Most of the canvases mentioned above are panoramic in vision and huge in scale. Some are even so big that they could only be carried to the exhibition halls in rolls. Though most of these paintings bearing the attributes mentioned above are from the period between the early-'70s and the mid-'80s, some exceptionally large canvases did reappear in his later years. The visions that helped him get into his stride resulting in the large canvases in the '70s, which now lie in possession of some of the country's most renowned collectors, resurfaced in another garb with a crop-field serving as the backdrop around the early 1990s, at the then Shilpangan gallery. Faiz Ahmed, the renowned journalist, who was at its helm, chanced upon the work when he went to visit the ailing master.

The maverick that Sultan was in his early years gradually evolved into a visionary. This transformation trails a long history of his personal growth in awareness of the world around him besides the comparable artistic development and social and religious engagements that excited his imagination before independence. His fluid movements through myriad social geographies and his proximity with some unique personalities, including his mentor cultural critic Shahed Suhrawardy in Calcutta (now Kolkata); his engagement with Allama Mashriqi's Khaksar movement that sought to organise the "self" to lay the ground for decolonisation; and his subsequent sojourns in America and Europe prepared him for his canvases which soon became populated with muscular men and women. To answer to the issues of contemporaneity and history, Sultan, unlike many of his modernist compatriots, never harboured an unseemly desire to exclude what is marked out as pre-colonial in the linear history governed by the academy.

Taking some obvious cues from Ashish-ur-Rahman Shuvo's account, encapsulated in the volume published by the Shilpakala Academy as a posthumous tribute, one can conclude that Sultan's vision was akin to that of an "aesthete" who developed a strong sense of "context". The perceived proponent of the new Bohemia was actually a self-appointed teacher of wisdom who saw shongshaar or quotidian life permeated with (good)will and beauty as an ideal site for the (re)production of both individual and social "self".

Sultan enframed the nation as one enormous village where he would plant the seeds of transformation by way of nurturing the future generation—the rural children—he believed, would thrive only through art and creativity. He has been associated with a number organisations that he had either attempted to set up or envisioned, though none had materialised since he neither had the heart, nor the discipline to sustain these projects. But the one that finally came into being was an informal institution—the village school he lovingly named Shishu Shargo (lit. Children's Heaven). His was a clearly defined social-aesthetic mission which never verged on the ethereal: "To will a change ... to recast anew," is "beauty", Sultan once declared.

The modernist master grew up in the company of the laity and was concerned about their natural bearings and their place in a rapidly changing society "where Western culture dominates" and "the idea of the krishi-culture (lit. agriculture) is yet to take root." One presumes that he was speaking in "aesthetical" terms rather than solely in relation to material organisation. With the ideal and the material serving as a continuum, Sultan could find a natural way of assimilating the Western with the Eastern, the classical with the popular; not to wilfully outline subjective fantasies but to bring into existence a "communal vision", that too from the edge of the mainstream society.

He chose to settle down in Narail, his home village, not to seek refuge in the bucolic distance, but to lend voice to the subaltern and to "talk back to the centre", vigilantly abrogating the colonial legacies that burden us to date.

The emergence of the "repressed" in S M Sultan's painting is thus a natural outcome of the life he lived. On the other hand, the creation of an artistic diction whose analogy can be found in the European Renaissance panoramic visions that sought to tackle religious themes as well as in Buddhists sagas depicted on the walls of Ajanta in India, thus, reflects what one may call a philosophical awareness about time and space. That the two divergent sources are brought into constellation with one another is a testimony to his rejection of linear time.

Sultan's hybrid language of art stems from his own context. That his language seems to reside between the Renaissance art's conglomeration of human figures awaiting emancipation and the traditional wall painting of the subcontinent, both depicting religious themes, opens his world out to visions of mythic proportion. But the myth-engendering Creole he developed also took Narail as one of the important points of departure. In fact, the stylistic rigour with which his every imagery is made to emerge, one which brings into alignment the contextual and the foreign, forming one complete whole, is launched from ground Zero of his motherland. The peasant population of his home village found their way into his canvases after considerable amplification in both spirit and physique. What one should note with care is that the emaciated, dispirited villagers some envisage from within the urban centres are nowhere to be found in Narail where there are peasants who exude health and vigour. Even if they seem like a far cry from the sturdy humans of Sultan's painting, they possess bodies that have once laid the ground for Sultan's vision of a coming society.

To conclude, one must cast an eye over the master's oeuvre informed with the position he cast and the multiple trails he left behind. Since Sultan, who left his mortal coil in 1994, went through a stylistic decline evidenced in his later works, especially works from the period when he was already bed-ridden, the "salt" he was made of must be recognised in relation to the series of works that sufficiently forwarded his vision—ones that still inspire awe. However, the issue of value judgment should not revolve around whether the latter-day drawings and sketches should be set aside to measure his worth. What is worrisome is that, from the glut of forgeries now circulating in the art market, how does one go about sifting for the ones that truly represent the master modernist whose idea of modernity never precluded the agrarian social ethos? In fact the agrarian social-cultural realm continually inspired his work as well as his idea of a new "sociality" in which the laity's position would be reclaimed as world-makers. If this lens serves as a guide, our search would be worthwhile in defining the very grains that went into the making of the Sultanian vision.

Mustafa Zaman is an artist, art writer and editor of soon to be launched magazine Art Plus

Comments