Nationalist forgettings

In 1950, just a little more than two years into the partition of the South Asian subcontinent, the octogenarian Abdul Karim Sahityavisharad (1871-1953) delivered a lecture in Chittagong, on the language and heritage of the Bangla language in the context of newly founded Pakistan.

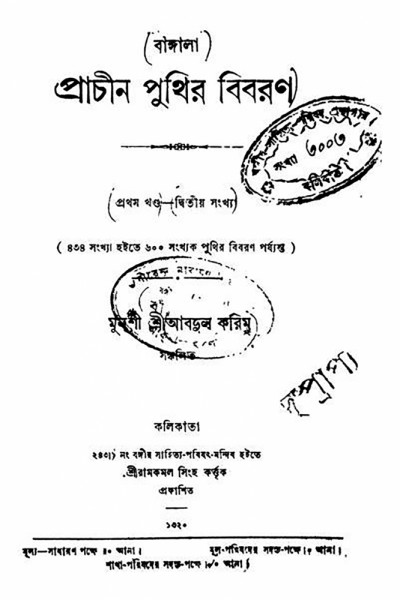

Karim had spent his entire life discovering the forgotten literary archive of Bangla, putting together a massive number of literary specimens of Bengali Muslims. He gained considerable acclaim from the Bengali intelligentsia in the undivided Bengal: almost all of his edited manuscripts came out from the Vangiya Sahitya Parishad established in 1893.

In his Chittagong speech, Karim made observations about the possible trajectory of Bangla language and literature in the wake of partition, which he had to willy-nilly accept since he was not involved in politics. Karim mentioned in his speech that there is no "shortcut" to a considerable position in literature. One has to go down to the very roots of Bangla language and literature and link it with the new scientific and rational stances. He highlighted in his speech that Bengali Muslims had a rich tradition in the ancient literary genres.

Bangla reached a high stage by imaginative contributions from litterateurs like Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Michael Madhusudan Dutta, Rabindranath Tagore, and Kazi Nazrul Islam. He argued that all literary geniuses – from William Shakespeare to Rabindranath Tagore – paid heed to ancient folk elements and created entirely new things by amalgamating tradition with imaginative assimilation of changing times. He noted that, as Pakistan came into being, certain literary figures were giving unviable directions in the realm of Bangla language and literature. Karim concluded that fraternity, love, and inclusivity is the way to go for engaging the people in literature.

After that conference, famous poet and editor Golam Mostafa (1897-1964) wrote an editorial in his literary journal Naobahar where he vehemently criticised Karim's speech in Chittagong. The key plank of Mostafa's diatribe was that the core of Sahityavisharad's speech went against the principles of Pakistan. He boastfully mentioned that Karim's speech was published with very poor arrangement, which was unprecedented from his own account.

In Mostafa's reckoning, Pakistan had accomplished a comprehensive "revolution", which went completely unacknowledged in Karim's speech. Mostafa sounded alarm that Karim's idea of continuity of the Bangla language was not only deeply problematic but shook the very core of Pakistan by being aligned with the concept of a "united India". Besides, Mostafa noted that Karim's speech resonated with the speech of Dr Muhammad Shahidullah delivered in the previous year at the Dacca session, where the latter mentioned that it is true that people here are Hindus and Muslims but the bigger truth stands that they are Bengali. For Golam Mostafa, both Sahityavisharad and Shahidullah had an important role in the cultural upbringing of Bengali Muslims in the final phase of united Bengal, but after achieving Pakistan, their lifelong discernment had been suspicious in terms of core creeds of the fledgling state.

Golam Mostafa also cast aspersions on the literary contributions of Kazi Nazrul Islam who had been named by Karim – along with Bankim, Madhusudan, and Tagore – as an iconic figure for any Bengali literary aspirant. Mostafa identified Nazrul as a sympathiser of "united India" who failed to rebel against the Hindu pantheon. For Mostafa, the projects of Bankim, Madhusudan, and Tagore were crystal clear in that their literary creations were concentrated mainly on Hindu traditions, except in stray instances like a poem of Tagore, named Shahjahan, based on Muslim theme.

To top it up, Mostafa questioned the authenticity of the entire lifelong project of Abdul Karim, terming it fraudulent. With shrill self-assurance, Mostafa mentioned that he had previously put suggestion to this "old man" to keep silent about ancient literature or punthi sahitya. He believed Karim had caused a huge disaster by handing over his discoveries to Dinesh Chandra Sen (1866-1939). He suspects the Muslim writer of ancient specimens could have a matter of deception, because the entire discourse was made by scholars Dinesh Chandra Sen et al.

Golam Mostafa, a famous literary figure of Bengal, had a considerable contribution in consolidating modern Bengali Muslim's literary manifestation. Mostafa used to sing the songs composed by Tagore, an author he greatly admired. However, he experienced personal traumatic incidents in his family during the partition of Bengal. His take on Sahityavisharad had been jarring, but this literary incident signifies the gravity of the situation prevailing just after the creation of Pakistan.

After the incident, Sahityavisharad wrote a letter to Dr Muhammad Shahidullah where he mentioned Golam Mostafa's criticism. In this personal letter, he argued that the way Mostafa discarded the merits of older Bengali literature had been foolish; that he wanted to erect a tower without laying the foundation – a vain wish. Karim further noted that Muslims of Bengal could not create a worthy literature during the span from late nineteenth century to 1950. Mostafa imagined that the creation of Pakistan was an event that authorised dismissal of the entire corpus of ancient Bangla literature.

Jingoism – a certain conception of the modern – and belief in a deterministic relationship between politics and culture that pushed a poet like Golam Mostafa into denouncing older traditions and disowning Nazrul. Unfortunately, this was not an uncommon incident in history that only happened in the early stage of Pakistan. Approaches and assumptions like that appear time and again in language, cultural, and social realms where power seeks to decide the terms of our existential relation to our past and our language, culture, and social relations.

Priyam Pritim Paul is pursuing his PhD at South Asian University, New Delhi.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments