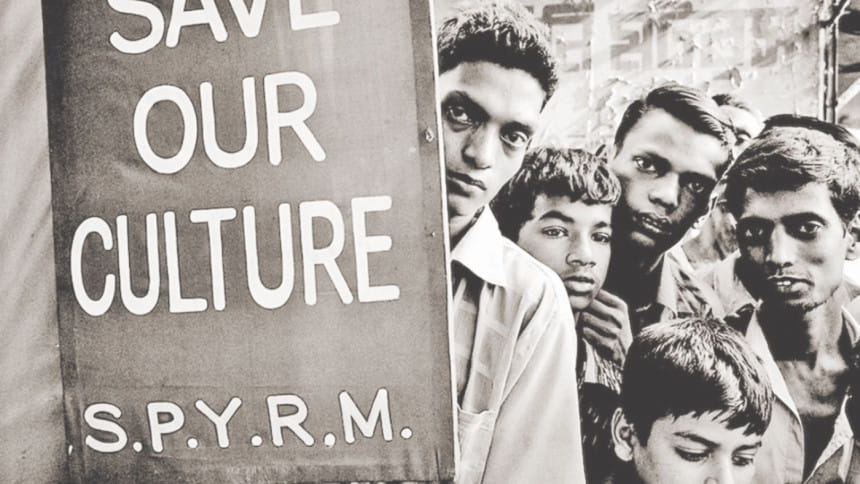

The plight of the linguistic minority

In Bangladeshi parlance, the Urdu-speaking Muslim people who had migrated to the then East Pakistan from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Rajasthan are categorised as 'Biharis'. The Bihari community is a linguistic minority and is exceptionally different from other minority communities of Bangladesh. The communal riot of Bihar during 1946-47 led this community to take refuge in the territory of Bangladesh. In the early days of Pakistan, there was confusion as to the legal identity of these people, i.e., whether they would be regarded as refugees or voluntary migrants or political asylees or stateless persons. In 1951 they were granted the citizenship of Pakistan and during the 24 years of Pakistani rules, they were a privileged community both in social and economic fields.

Because of their active anti-liberation role, the Biharis became subject to widespread political persecution preceding and during the 1971 liberation war of Bangladesh as well as in the aftermath of liberation. After Independence of Bangladesh, the Government of Bangladesh promulgated a set of laws that were intended to manage abandoned properties. These laws applied to a large extent against the Biharis, to confiscate not only residential but also commercial and movable properties including Cash, Ornaments and Bullion. The consequences of operation of abandoned property laws have been, simply, gross denial of freedom and liberty, and institutionalisation of systematic socio-cultural, economic and political deprivation of Bihari community in Bangladesh. They have been displaced and lost everything; thousands of middle class families rendered to paupers overnight. In order to save their souls had gone to the ICRC sponsored camps. Since then, the Biharis are suffering from a crisis of their legal identity and status.

In 1972, following the creation of Bangladesh, an estimated 1,000,000 Urdu speakers were living in settlements throughout Bangladesh awaiting “repatriation” to Pakistan. Agreements between Pakistan, Bangladesh and India in 1973 and 1974 resulted in some 178,069 members of this community being “repatriated” from Bangladesh to Pakistan between 1973 and 1993 out of some 534,792 who had registered with the ICRC for repatriation. At present, it is generally estimated that there are more than 300,000 Biharis in Bangladesh, half of whom live in 116 camps all over the country. For several decades the successive governments of Bangladesh have been treating the Biharis who opted for repatriation to Pakistan but are left in Bangladesh as 'refugees', not as 'citizens'.

In 2003, in the case of Abid Khan and others v Govt. of Bangladesh and others (55 DLR), a division bench of the High Court Division held that the ten Urdu-speaking petitioners, born both before and after 1971, were Bangladeshi nationals pursuant to the Citizenship Act, 1951 and the Bangladesh Citizenship (Temporary Provisions) Order, 1972, and thereby directed the Government to register them as voters. The Court further stated, quoting from an earlier case of Mukhter Ahmed v Govt. of Bangladesh and others (34 DLR) -“the mere fact that a person opts to migrate to another country cannot takeaway his citizenship.”

The effect of the 2003 decision was limited to the ten petitioners. Ultimately, the Supreme Court of Bangladesh had to confirm that Biharis are citizens of Bangladesh in 2008, in the landmark decision of Md. Sadaqat Khan and others v Chief Election Commissioner (60 DLR), the High Court Division reaffirmed that all members of the Urdu-speaking community were nationals of Bangladesh in accordance with its laws and directed the Election Commission to enroll the petitioners and other Urdu-speaking people who want to be enrolled in the electoral rolls and accordingly, give them National Identity Card without any further delay.

The Election Commission very swiftly issued National Identity Cards to any member of the Urdu-speaking community who applied for one and who met the legal and administrative requirements. The Urdu-speaking community can no longer be viewed as stateless or refugee, as they are considered to be nationals of Bangladesh. As per art.6 of the Constitution they are 'Bangalis' or 'Bangladeshis' not 'Biharis' or 'stranded Pakistanis'. They are entitled to apply for administrative and judicial remedies in accordance with the laws of Bangladesh, in the same manner as any other Bangladeshi citizen.

This minority group is obviously a backward section of the citizen and has long been ignored in the development discourse of Bangladesh. For more than four decades they are deprived from all the basic human rights. Particularly those living in camps are facing social exclusion and severe discrimination in every aspect of life- education, employment, health services, business, access to justice etc. Mainstreaming of this group is a crying need of the time.

The writer is a law student, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments