Remembering and Rereading Rokeya: Patriarchy, Politics, and Praxis

I repeat the same truth, and, if required, I will repeat it a hundred times.

— Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain

(translation mine)

What's the worst that could happen to me if I tell this truth?

—Audre Lorde

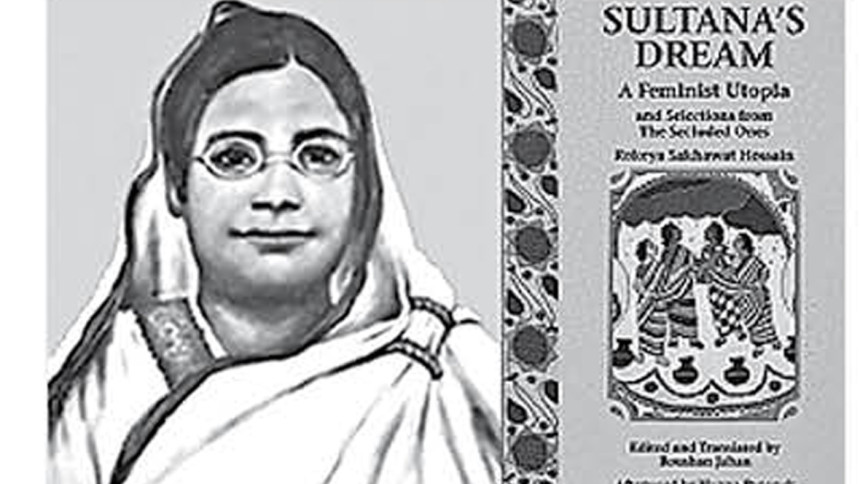

December 09 marks both the birth and death anniversaries of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880-1932). The Rokeya Day in Bangladesh also falls on December 09. Indeed, Rokeya has by now been institutionalized, iconized, and, for that matter, even reified. This means a certain misappropriation and depoliticization of her work as well. But there are now several biographies of Rokeya and scores of books and articles on her. Although I do not intend to recount Rokeya's biographical details here, I should stress the point right at the outset: Rokeya's life as a Muslim woman—lived courageously and even dangerously—illustrates nothing short of sustained struggles against religious bigotry, lack of education, shifting vectors and valences of colonialism, patriarchy affecting the practice of everyday life, and other forms and forces of oppression in colonial Bengal in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Theorist-activist, essayist, fiction-writer, poet, translator, journalist, educationist, organizer—and an organic intellectual in her own right—Rokeya produced a remarkable corpus of written works, making distinctive contributions to Bangla literature while articulating—with full force—the cause of women with a particular, if not exclusive, focus on their education and emancipation. Roushan Jahan already characterized Rokeya as "the perceptive feminist foremother," given the ways in which she anticipates a constellation of feminist questions and concerns broached later, although Rokeya and what a whole host of third-world feminists have called "Western, white feminism" do not go hand in hand.

Rokeya's important works include Motichur, vol. 1 (1904); Motichur, vol.2 (1921); her only novel Padmaraag (1924); and Aborodhbashini (date uncertain), among numerous others. Rokeya knew five languages—Bengali, English, Urdu, Arabic, and Persian—while she directly wrote in three of them—Bengali, Urdu, and English. Her work "Sultana's Dream"—a novella first written in English and later translated into Bengali by the author herself—is usually described as "a feminist utopia" that, as Roushan Jahan rightly points out, "antedates by a decade the much better-known feminist utopian novel Herland by [the American novelist and poet] Charlotte Perkins Gilman" (1860-1935).

Yet another work in English by Rokeya is instructively titled "God Gives, Man Robs" (1927). It's a powerful essay that carries her famous words: "There is a saying, 'Man proposes, God disposes,' but my bitter experience shows that God gives, Man Robs. That is, Allah has made no distinction in the general life of male and female—both are equally bound to seek food, drink, sleep, etc., necessary for animal life. Islam also teaches that male and female are equally bound to say their daily prayers five times, and so on." Some contend that this work advances Rokeya's nuanced version of what is called "Islamic feminism" at a conjuncture that witnesses androcentric and colonialist abuses of religion itself. Rokeya of course already puts it clearly and simply: "Men dominate women in the name of religion" (translation mine).

Although it is impossible for me to characterize or summarize the entire range of Rokeya's written works, I can readily call attention to one particularly predominant concern that prompts, energizes, and constitutes the very production of her words and her world: the woman question relating to the question of the total emancipation of humanity—of both women and men. And the woman question itself is constitutively and irreducibly a revolutionary question insofar as in the final instance it prompts us to interrogate, combat, challenge, and even destroy the historically produced system of male domination called patriarchy on the one hand, and, on the other, those systems of domination and exploitation that variously support and even enhance patriarchy itself. And Rokeya's specifically revolutionary stance decisively resides not only in raising the woman question but also in making that question integral and inevitable to the entire horizon of her work—literary, pedagogical, organizational, social, familial.

2

Let me return to "Sultana's Dream" (1905), because a number of its aspects still continue to remain ignored, although these days this work often gets discussed by those who claim to do postcolonial studies. I think this work is more than just a subversive and satirical intervention in the genre of what might be called "political dream-fiction" or "political science fiction." And I read it as a work offering—through a radical reversal of the patriarchal or male-dominated order of things—a social imaginary that looks forward to, or even creates in imagination, a space and a place in which not only patriarchy spells out its own death but in which also science, political economy, ecology, and the forces of nature and the forms of justice remain adequately responsive to one another in the best interest of not only all humans but also all living beings themselves. And, thus, this work remains opposed to the destructive and oppressive logic of colonialism, militarism, and masculinism—and even anthropocentrism—profoundly interconnected as they are. In "Sultana's Dream," Rokeya also brilliantly anticipates a version of feminist science, offering a critique of colonialism's relationship with science as a power/knowledge network. Indeed, "Sultana's Dream" is, thematically and stylistically, the first work of its kind in the entire history of literary productions in Bengal.

Rokeya is also an early but powerful theorist of women's liberation, a tireless organizer, an exemplary pedagogist of hope, and even a revolutionary in her own right. And her revolutionary moves reside in ways in which she gave voice, at the beginning of the twentieth century, to an entire generation of women struggling in confinement, or struggling against the purdah system itself, against the abuse of religion, against the shackles of not just double but multiple colonizations of women by patriarchy and colonialism and 'feudalism,' for instance.

Rokeya's work Aborodhbashini is often reckoned the locus classicus of the discourse surrounding the purdah system, but does Rokeya combat the system of women's seclusion and segregation à la Western feminists? No. For Rokeya, purdah is not just a floating signifier but heavily meaning-loaded, conjunctural, contextual; it's more than an external veil covering a face or any part of the body, but it refers to an entire system of both mental and physical imprisonment to which the questions of colonial patriarchy and patriarchal colonialism remain relevant. Rokeya says: "The Parsi women have gotten rid of the veil but have they got rid of their mental slavery [manosik dasattya]?" (my translation). It's here where Rokeya not only anticipates Kazi Nazrul's own formulation of "mental slavery" (moner golami)—but she also accentuates--way before Frantz Fanon and Paulo Freire and Ngugi wa Thiong'o—the need for anti-colonial, emancipatory education for both women and men.

Last, Rokeya is also a politically engaged satirical poet whose apparently playful wit and sarcasm could be devastatingly subversive at times. Some of her famous poems include "Banshiful," "Nalini o Kumud," "Saugat," "Appeal," "Nirupam Bir," and "Chand." And her poetic but satirical interventions at various levels keep making the basic point about praxis itself: your silence is not going to protect you. Notice, then, a stanza in a poem she wrote as a response to those sell-outs, those middle-class bhadralok collaborators of the Raj who not only resorted to silence, but who were also nervous about losing their "honorific titles," in the face of the Indian nationalist movement gathering momentum in 1922:

The dumb and silent have no foes

That's how the saying goes

All of us with titled tails

Keep so quiet telling no tales

Then comes a bolt from the blue

Passes belief, but it's true

All of you who did not speak

Will lose your tails fast and quick

Come my friends and declare now

In loud and loyal vow

Listen, ye world, we are not

God's truth, a seditious lot

(quoted in Bharati Ray's Early Feminists of Colonial India)

I've so far quickly contoured only a few areas of Rokeya's interventions, but I've tried to convey at least the impression that honoring the legacy of her work calls for rereading, remobilizing, and even reinventing Rokeya in the interest of our struggles for destroying patriarchy and all systems of oppression.

Azfar Hussain teaches in the Integrative, Religious, and Intercultural Studies Department within the Brooks College of Interdisciplinary Studies, Grand Valley State University in Michigan, and is Vice-President of the Global Center for Advanced Studies, New York, USA.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments