When the Gypsies Came to Town

It happened sometime in the winter of 1959. There was a ripple of commotion in the 'kancha bazaar' (kitchen market) in Dinajpur town. Someone gave a clarion call, "The gypsies are here. Allah save us! Secure your things." It was as if a calamity had descended on the small town. Sajeed our domestic servant came running home from the bazaar and excitedly broke the news.

The kancha bazaar in those days was the hub of news, both real and imagined and the pulse of society. There was an immediate stir in our family. Everyone spoke excitedly. Mother was worried. Our Dadi (paternal grandmother), a pious, conservative lady of the old school who knew enough about gypsies from her childhood days in Malda, declared with a magisterial flourish that they were evil people. Prejudice and fascination combined with a litany of negative attributes ranging from: thievery, witchcraft, sorcery, black magic, kidnapping of children were all associated with them. Even our young teenage paternal aunt and uncle chipped in, " these people know Jadu" (magic). However, what struck me as a bit odd even as a 5 year old, was the sudden furor the news had aroused in an otherwise quiet, orderly household. I became very curious. Who were these strange people? Our front and backyard gates were promptly locked. It was debated if we (children) should be sent to school that day or not? Even our beloved pet dog Pinky sensed something was wrong and barked incessantly. Only our father maintained his calm. With a huff he rode off in his bicycle to his office, glad to get away from it all. "Don't forget to notify the police," mother called after him. Nobody cared to recall then, that our celebrated national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam was enamored of the gypsy girl, and had admiringly written an enchanting ode to the dancing Iranian girl who played the tambourine.

It was difficult for us children to go off to sleep that night. We tossed and turned, dithered and shuddered. Mother scolded us. We were told to close our eyes and go to sleep. We feigned sleep for a while, before sleep and "dreamland" overtook our weary souls. However, as children our fear and excitement was palpable. Then all hell broke out the very next morning. Sajeed raised the alarm, "Amma O Amma, amgo khaise re khaise, gypsy ra bashar pechone aise!" (Mother O mother! We are undone. The Gypsies are right here in our backyard!") We all woke up with a start. For the first time I saw a look of concern on my father's face. He told everyone to stay indoors while he and uncle Akram hurried to our backyard to investigate. Sajeed was right. The house we lived in was previously owned by a Hindu pleader who had left for India soon after the partition. It stood on an elevated plot of land. In our backyard was a small patch of land we used as a kitchen garden, at the edge of which was a sheer drop of about four feet into a shallow, murky, dying canal called the Ghagra. It was once a prominent canal dug by Raja Ramnath of Dinapur for purposes of drainage and sanitation to ensure public health in the town. However, during our time, the Ghagra was silted and had very little water except in the rainy season. The canal previously drew water from a nearby ancient river called the Kanchan, mentioned even in the old Hindu scriptures. Sadly, when we saw the Ghagra, it slowly meandered through the town like an oversized drain carrying filth. Viewed from our backyard across the canal, lay a vast stretch of uninhabited land where the cattle crazed. The Gypsies had camped there. It was also there that the local communities of the dom, chamars and sweepers, the lower caste Hindus, used to let loose their pigs to forage. In winter we used to watch the hogs from our rooftops and wonder aloud why the pigs pictured in our English story books were always white or pinkish in color, whereas, the ones we saw were dark, dirty and wallowed in filth. As small children, I and my older sister naively believed that since the English sahibs were white, so too, must be their pigs!

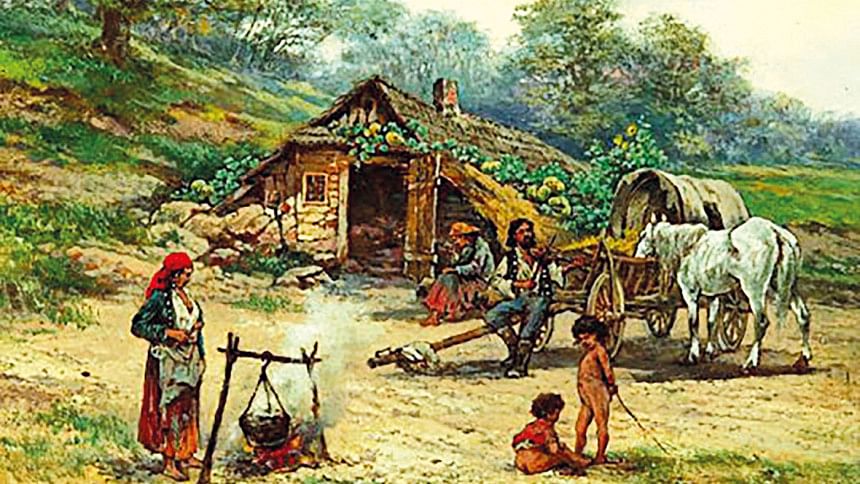

That day, we all ran up to the rooftop to watch the gypsies from a distance. There were probably four families of them who had pitched a few tattered tents. Their noisy, disheveled children were running around, while their donkeys grazed. But what alarmed us was the big black guard dogs they had brought along. These fierce dogs had already seen us and were furiously barking away. We despaired for our little Pinky and resolved to keep her indoors. Gypsy men in loose garments and headgear (turban) were busy scrounging the wasteland for firewood and dry leaves, while their women in billowing colorful Ghagrara (skirt) were already busy with their cooking pots. This was for the first time that I and my sister had seen gypsies. We were fascinated. Racially, they clearly stood apart from us. They were taller and bigger. Their skin color ranged from swarthy to fair. They spotted us on the rooftop, seemed to wave at first and then jeered. Our elders immediately brought us down into the house.

Soon the local administration sent for the police. There was some altercation between the gypsies and the police. Their children cried and the dogs barked menacingly. Later our father said that the gypsies had prayed for a day or two of reprieve before leaving. They had come from across the Indian border (West Dinajpur, West Bengal), to try and sell their wares in our part of Dinajpur. It was said that they originally belonged to Rajasthan, India.

Next day all was quiet. The gypsies stayed put and we went off to school. Meanwhile, a most unnecessary incident took place. Our house-servant Sajeed had opened the rear boundary wall door of our house to let in the sweeper. As he did so, he was startled to see at close proximity gypsy women washing utensils and clothes in the brackish water of the Ghagra. They grinned at him and said in a smattering of Hindustani if the Begum Sahiba (meaning our mother) of the house would be interested to see their goods. A scared Sajeed lost his cool. He was abusive and threatened them with a piece of firewood. The enraged gypsies in turn screamed obscenities and lobbed a few bricks into our backyard. However, our uncle Akram managed to calm things down. The gypsy women grudgingly departed. Later, Sajeed was severely taken to task by our parents for his folly.

Couple of days later, while we were at school a commotion broke out again at the gypsy camp. This time the local police came and forcibly evicted them amidst much hullabaloo. Within an hour the gypsies after hastily packing their belongings on their donkeys left, all the while gesticulating wildly and taunting the police. They also left behind quite a mess, which was later set on fire.

As night fell on us with a hush, I ran up a high fever. Our Dadi prayed beside my bed, while mother gently wept. Aunt Sara anxious at the sudden onset of my fever, quipped, "It's all Sajeed's fault. He should never have behaved so rudely with them. Now the gypsies have put a curse on this house." Our father scoffed. "Nonsense" he said. "It's just a bloody coincidence. Don't be so superstitious. It's un-Islamic."

Waqar A Khan is Founder, Bangladesh Forum for Heritage Studies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments