Justice delayed, justice denied

- Over 2,000 children killed by toxic paracetamol between 1980-92

- Corruption sabotaged the criminal cases

- Never-ending High Court stay orders prevent cases coming to trial

- Families kept in heart-breaking wait for justice in one of the worst ever crimes

- One case reopens today upon STAR inquiry; one company was not even prosecuted, two other cases stuck in stays, another acquitted

Manufacturers of adulterated paracetamol syrups, which caused the deaths of as many as two thousand children sixteen years ago from fatal kidney disease, have escaped punishment due to an extraordinary combination of corruption and mismanagement in the Directorate of Drug Administration (DDA) and other government agencies, an investigation by The Daily Star reveals.

In December 1992, chemical analysis proved that paracetamol syrups manufactured by five companies -- Adflame Pharmaceutical Ltd, Polychem Laboratories Ltd, BCI (Bangladesh) Ltd, Rex Pharmaceutical, and City Chemical and Pharmaceutical Works Ltd -- contained a lethal chemical diethylene glycol.

The tests on the drugs were above suspicion; using newly installed gas chromatography equipment, they were conducted by the government's own drug testing laboratory under direct supervision of an expert consultant from the World Health Organisation (WHO). The results of subsequent independent testing -- undertaken in laboratories in the US and obtained by The Daily Star -- confirmed the results.

Yet the High Court was persuaded in 1994 to order a temporary halt to criminal proceedings against the owners, directors, and managers of four of those companies on the basis of a circular published by DDA containing highly misleading information suggesting that Bangladesh had no adequate test facilities.

Read all stories on paracetamol syrup scam -

- Justice delayed, justice denied

- All records 'lost' from drug office

- JUSTICE DELAYED, NOT DENIED

- Drug admin official couldn't care less

- A regret for life

Moreover, in relation to the cases involving Polychem Laboratories and BCI Bangladesh, at no time in the last 15 years has DDA taken any action to correct the High Court's mistaken impression about the tests, and argue for the stay orders to be vacated. Remarkably, as a result, criminal proceedings against the defendants from those two companies have been stopped for 15 full years.

The cases involving two other companies have fared no better. While the High Court stay of proceedings relating to Adflame Pharmaceutical was vacated two years ago -- 13 years after it had been initially imposed -- the Dhaka Drug Court promptly lost all the papers, and the public prosecutor remained unaware that the proceedings could actually continue.

It was only after The Daily Star informed the public prosecutor earlier this month of the new legal situation, and a massive four day hunt finally resulted in the discovery of those files, that the judge of the drug court scheduled today for reopening the proceedings.

The case against the owners of Rex Pharmaceutical is the only one of the four cases that resulted in a trial while City Chemical and Pharmaceutical was never even prosecuted.

In November 2003, the judge acquitted the two defendants of Rex Pharmaceutical, questioning the integrity of the chemical tests. The court ruling however shows that the court was not informed of how the tests had been undertaken and the role of WHO in ensuring their accuracy. Moreover, the court was also not told that the law in fact did not permit it to question the accuracy of the tests. But DDA never appealed against the acquittal.

The decision in 1992 by DDA not to prosecute City Chemical and Pharmaceutical, although its syrup also tested positive for diethylene glycol, raises further questions about the government agency. At that time a director of the company was Khondker Mahtabuddin Ahmed who was the father-in-law of Barrister Abdus Salam Talukdar. Talukdar was the then secretary general of the erstwhile ruling party BNP and also its minister for local government and rural development. There appears no other explanation for Khondker Mahtabuddin Ahmed escaping prosecution, than this political connection.

HUNDREDS OF DEATHS

This remarkable story of corporate killing and impunity started in the early 1980's when significant numbers of young children were being admitted with serious kidney problems to Dhaka's PG Hospital, now known as Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University Hospital. The cause of the renal failures was not known, and most of the children died. When, in 1986, Dhaka's Shishu Hospital opened up a new nephrology ward, it also became inundated with children suffering from similar unexplainable renal failures.

The problem was even faced by Bangabhaban Medical Clinic, which provided health care to the president's and prime minister's staff and their family members, where about 20 children died. One of those who died from a kidney failure was a year and a half old Tanvir Ahmed whose father worked as an office assistant in the president's house.

"I cried, and begged the doctors to save the life of my child. I could not save him. I lost such a wonderful boy," Tanvir's mother, Peyara Begum, told The Daily Star. Another who died the same way was seven-year old son of Rakhal Chandra Barua, a chauffeur in the prime minister's transportation pool. "The doctors told me that he died from a kidney failure. I could not understand why he died so fast. I buried my child with my own hands, when it should have been the other way around," he said.

A Scottish specialist, sent by WHO in 1988 to try and find out the cause, left Bangladesh after two months none the wiser. It is estimated that a total of 2,700 children died in unexplained circumstances from kidney failures between 1980 and 1992.

It was Dr Hanif -- now a professor in Dhaka Shishu Hospital -- who finally worked out in the early 1990's that the cause must be adulterated paracetamol syrups, where the harmless diluent propylene glycol had been replaced with the toxic diethylene glycol, a much cheaper chemical but deadly if swallowed.

With DDA failing to organise tests of paracetamol syrups, Dr Hanif was himself forced to send a sample of the syrup used in both Shishu hospital and Bangabhaban clinic -- Adflame's 'Flammodol' -- for testing in the US. With the results showing that the sample had tested positive for diethylene glycol, Hanif wanted to publicise the situation immediately but was advised by his hospital authorities that more evidence was required. He therefore sent further samples to the US.

The results took a long time coming, and feeling the matter was of urgent public importance, in November 1992 Dr Hanif told a press conference of the results, and provided other evidence that suggested other paracetamol syrups were also contaminated.

GOVERNMENT TESTING

With the issue on the front page of newspapers, DDA was forced to take immediate and forceful action. It sent 135 samples of syrups to the government run Bangladesh Drug Laboratory (BDL) to be tested under the supervision of a WHO consultant, SK Roy.

As BDL itself did not have a gas chromatograph, Roy contacted Essential Drug Company Limited (EDCL) where the equipment had just been installed. "Roy came over to visit the laboratory and to check if the laboratory equipment was appropriate," recalled Anisul Islam, EDCL's then managing director, adding, "During the tests, Mr Maleque, the head of BDL, and Dr Zakaria, his assistant at BDL, were present along with WHO's Roy."

Shafiqur Rahman, the deputy manager of EDCL at the time, also remembers what happened, "These three men themselves conducted the test. They just used the equipment in our laboratory. It was totally under their supervision."

The results of the tests were known a few weeks later on December 3, 1992, with five brands being tested positive for containing 10 to 20 percent diethylene glycol.

However, just two days later, the erstwhile director of DDA Mukhlesur Rahman [now deceased] did something inexplicable -- with serious consequences for the subsequent prosecution. He published a circular which stated, "As there is no appropriate arrangement in the government laboratory for detecting Diethylene Glycol in Paracetamol Syrup, samples of some of these brands have been sent abroad in November 1992 with the help of the WHO."

This statement was highly misleading as it suggested that BDL could not undertake proper tests in Bangladesh. In fact, Mukhlesur Rahman knew perfectly well that accurate tests had just been completed by BDL under WHO supervision using the right equipment.

Abul Khair Chowdhury, an assistant director of DDA who in 1992 was a drug superintendent responsible for the investigation and prosecution of the three Dhaka cases, admitted to The Daily Star that he could find no reason why the circular stated that the tests could not be done effectively in Bangladesh. "I don't know why the notification was issued. The notice should not have contained this clause," he said.

CRIMINAL CASES FILED

Under public pressure on December 19, 1992, on the basis of the government laboratory tests, Abul Khair filed criminal complaints with the Dhaka Drug Court against directors and managers of three of the companies -- Adflame, Polychem, and BCI Bangladesh -- alleging that they had manufactured 'adulterated' and 'substandard' drugs. The offence allows the court to sentence a convicted person to 'rigorous imprisonment for a term which may extend to ten years'. A similar complaint was made by an erstwhile drug superintendent Tomas AK Biswas with the Mymensingh Drug Court against Rex Pharmaceutical owners.

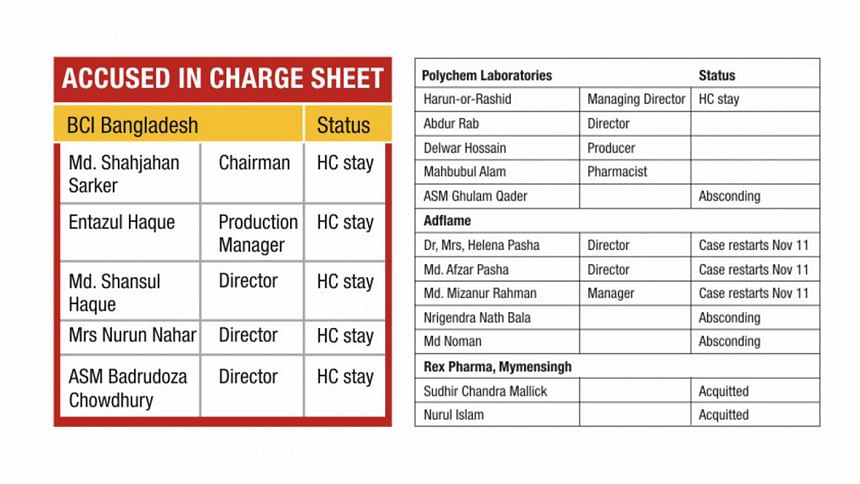

Following the courts' summons most defendants surrendered and obtained bail, although some did abscond. The drug courts then issued charge sheets involving a total of 17 defendants.

The non-absconding defendants in each of the four cases then filed petitions with the High Court seeking stay of the criminal proceedings. The director of DDA had himself provided the companies with the perfect loophole. The defendants argued that since DDA had itself admitted in its December 1992 circular that Bangladesh did not have appropriate facilities to test diethylene glycol, the test results undertaken by BDL could not be used as a basis for prosecution.

Without being informed of the nature of the testing, this argument must have appeared to the High Court judges highly plausible -- and it is hardly surprising that in each case, the judges issued a rule upon the government to come and explain why the cases should not be set aside. The order stated that 'pending disposal of the rule, all criminal proceedings should be stayed'.

If that was not enough, DDA then did a further thing that muddied the legal waters. Against each defendant Abul Khair filed an additional more serious case under the Special Powers Act (SPA) 1974. The problem with filing an additional case, however, is that the law in Bangladesh does not allow a person convicted or acquitted for one offence, to be subsequently prosecuted for a separate offence involving the same set of circumstances. This meant that as soon as either of the two cases had resulted in an acquittal or conviction, the other case would have to be scrapped.

BCI BANGLADESH, POLYCHEM LABORATORIES

All of the drug court cases were stayed in mid 1994; it was now the job of the Attorney General's Office and DDA to argue that the stays should be vacated.

Since those proceedings were taking place in the context of deaths of thousands of children, one would have expected the Attorney General's Office and DDA to make strenuous attempts to schedule a date for a High Court hearing to prove that tests for diethylene glycol could be done -- and were in fact done -- successfully in Bangladesh.

However, nothing like that happened. Over a fifteen year period no action was taken to get the cases restarted. Till today, the High Court orders, which stayed the criminal proceedings against nine defendants, remain in place, unchallenged.

We asked Abul Khair, the DDA complainant in both those cases, to explain his total lack of activity over a 15 year period. He said, "I did not know that the cases were stayed until you told me about it. I never heard any information like this. No notice ever came to me." He did not accept any responsibility for his lack of action saying during that period of time he kept being transferred to different parts of the country.

ADFLAME

The case against the six defendants from Adflame Pharmaceutical has always been the strongest. Its syrup had been used at both Shishu hospital and the Bangabhaban clinic where hundreds of children had died. Moreover Flammodol had tested positive for diethylene glycol not only in the government tests but in two separate tests in two different US laboratories organised by Dr Hanif -- one in early 1991 and again in late 1992.

In March 2007, the ruling that had stayed the criminal proceedings came up for final hearing at the High Court. No lawyer for the defendants was present. Justices Sharif Uddin Chaklader, and Sheikh Abdul Awal ruled, "The offence disclosed is a very heinous offence as it relates to the life of infants who were treated at different hospitals. It is a crime against society as such the trial should be held to find out whether the allegations are true or not. We find no substance in this rule." The criminal proceedings could now restart -- 13 years after being stayed.

On October 5, 2007 the High Court sent the court orders and relevant papers back to the Dhaka Drug Court. They were received by Abdul Haque, a court clerk. He however did not inform anyone in the court, and placed the papers among the pile of 'disposed' files. Neither the judge nor the public prosecutor knew that criminal proceedings could now start again. DDA by then had long forgotten about the cases.

The drug court only came to know about the 2007 High Court order three weeks ago when The Daily Star told the public prosecutor about it. Immediately the judge asked to see the case papers, but for four days the papers could not be found.

"It was a mistake," Abdul Haque told The Daily Star. Another court clerk was less generous. He said, "It cannot be a mistake. There must be something else involved. There is no other way that the papers could otherwise be found among the disposed off files."

The judge has now fixed today for restarting the trial. The current status of the Special Powers Act case against Adflame directors is not known.

REX PHARMACEUTICAL

The case against the two owners of Rex Pharmaceutical in the Mymensingh Drug Court is the only one that resulted in a trial.

In June 1998 -- with the drug court case stayed by the High Court -- the two defendants obtained a discharge order from the additional sessions judge in relation to the charge under SPA 1974. The court ruled since the defendants were already being prosecuted under the Drugs Ordinance, they could not be prosecuted under SPA.

However, it appears that the prosecutor did not inform the judge that he could only discharge the case, if the defendants had already been acquitted or convicted for an offence -- and the drugs offence case there was far from making it to trial, let alone an acquittal or conviction. The government failed to appeal against the discharge order.

The drug court case however still remained. In August 2002 -- after eight years of inaction -- the High Court vacated the stay order. Justices Hassan Ameen and Tariq-ul-Hakim ruled, "The question as to whether the case in question had been filed on the basis of chemical examination by analysts from the Central Drug Laboratory is a matter to be decided at the time of final hearing of the case…." It is not known why the High Court dealt with this case so much more quickly than the other three cases that had been stayed.

The case papers were then sent back to the Mymensingh Drug Court and the criminal trial restarted against the two defendants. After hearing the evidence, Judge Shahiduzzaman acquitted the two men. "It is found that the chemical examination of the seized paracetamol syrup was not properly done," the court ruled. The judgment also stated, "The accused person have already faced a trial before a competent court over the self-same occurrence and now they are facing the trial again."

The Daily Star however uncovered serious flaws in the evidence given at the trial. There was no evidence given at the trial about the role of WHO in supervising the quality of the tests; the report produced by WHO Consultant SK Roy, which The Daily Star has seen, was not even shown to the court. The judge suggested that since the test results had not mentioned that the test had been done at EDCL, questions were raised about the result; yet the prosecutor did not inform the judge that it was no requirement for the test result document itself to state where the tests had taken place. The key question was whether the test had been done by analysts from the government's drug testing laboratory on suitable equipment. And about this, there is no doubt -- but this was not made clear to the judge.

The prosecutor also did not inform the court that the Drug Act 1940 did not allow the government laboratory report to be questioned, since it states that a test result signed by a government analyst should be considered 'conclusive'. The only exception to this would be if the defendant had written to DDA questioning the test itself, within 28 days of receiving the results -- something that had not happened in this case.

In addition, the prosecutor again failed to inform the drug court judge about what the law says about a 'second trial' in connection with an already adjudicated occurrence. The judge stated that the two defendants were now facing a second trial relating to the self-same occurrence -- suggesting that this was an additional reason to acquit the defendants. However, the judge was not informed that the Criminal Procedure Code states that 'discharge of the accused' -- which is what happened to the defendants in relation to the case under SPA -- did not constitute 'acquittal'. The case before the drug court was therefore not a 'second trial'.

CITY CHEMICAL AND PHARMACEUTICAL

City Chemical and Pharmaceutical was one of the five companies whose paracetamol syrup, Paracit, was found to have diethylene glycol. The syrup not only tested positive in the analysis done in Bangladesh, but also in those independently done in the US. The test results, undertaken at the State Laboratory Institute in Massachusetts stated 'Batch 14' of Paracit, manufactured in '9-92' tested 'positive' for diethylene glycol.

However, when on December 19, 1992, Abul Khair filed criminal complaints against three companies, he did not prosecute City Chemical. When journalists at the time questioned the reason for that, the director of DDA said the company claimed that the sample tested in the laboratory was not its product. However, it seems highly improbable that both WHO supervised tests in Bangladesh and the further independent tests in the US, were both inaccurate. A much more likely reason for the decision not to prosecute, concerns the fact that one of the owners of the company was Khondker Mahtabuddin Ahmed, the father-in-law of Barrister Abdus Salam Talukdar. Talukdar was the then secretary general of the erstwhile ruling party BNP and also its minister for local government and rural development.

When we asked Abul Khair why he did not prosecute City Chemical in 1992, he repeatedly denied that the company was connected to paracetamol adulteration. He claimed that all the companies that were found positive for adulteration were prosecuted. "None were spared," he said.

The families of those who died feel totally let down by the government. On being told by The Daily Star how the justice system dealt with the companies, Rakhal Chandra Barua, the father of seven-year old Bablu who had died 19 years ago said, "I am amazed how such types of cases remain unattended for such a long time. What else can I do except shedding tears as I am just a poor employee at Bangabhaban."

Peyara Begum, the mother of a year and a half old Tanvir, said, "This is the state of justice in our country. We want punishment for those involved in the incident. We want them hanged or jailed."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments