Learning from Bangabandhu's Writings

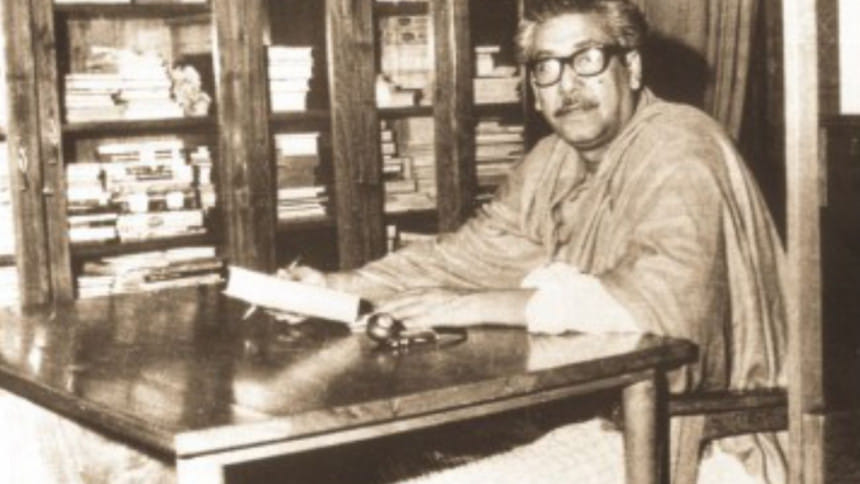

Translating Bangabandhu's unpublished works has allowed me to see how and why Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, a boy from a small, and in those days relatively remote rural community of East Bengal, became the father of our nation. It has given me the opportunity to appreciate too why he is the most remarkable figure in Bangladeshi history; it has also enabled me to learn a lot about the epic and heroic dimensions of his life. In translating his works, I have been better able to appreciate his developing vision about the country that he would eventually create.

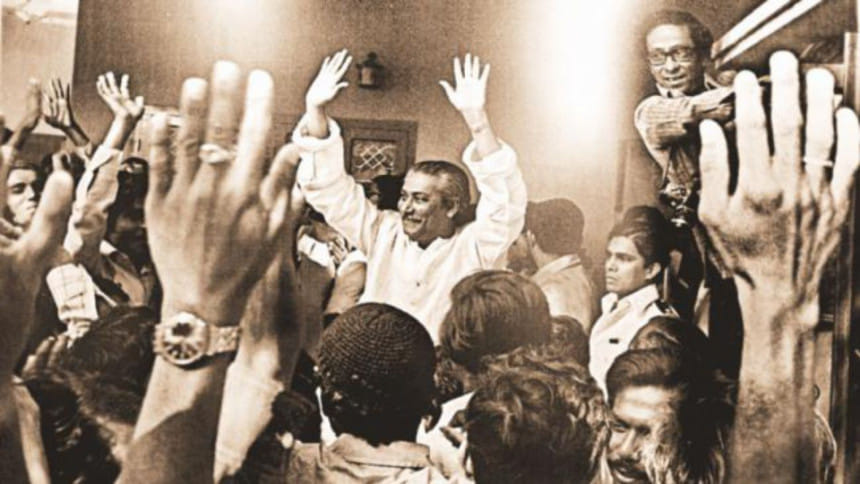

In this month of mourning, let us remember that Bangabandhu always attempted to come close to the people of his country. That is why he had chosen to live not in a heavily guarded government house, but in his own one. We must also remember in this context Bangabandhu's immense and unflagging courage and selflessness, amply demonstrated in all phases of his life. Again and again, in The Unfinished Memoirs and the Prison Diaries we see how he showed immense courage and resolve by standing up against overpowering forces and sacrificing himself for causes he believed in. Again and again, we witness him speaking truth to power and becoming in the process the kind of leader who would inspire others to drive out the brutal and powerful occupation army that had come to bloody his beloved Bangladesh. As he notes on one occasion, "To do anything great, one has to be ready to sacrifice and show one's devotion"

Bangabandhu's life, as recorded in The Unfinished Memoirs and the Prison Diaries, is one of unending sacrifices, unremitting courage, and unswerving commitment. In these works, he demonstrates repeatedly his ability to bear immense pain for a cause. His capacity for sheer hard work is astonishing. In addition to the sacrifice he had made in terms of family, education and finances, he had to work endlessly and undergo constant travel, and endure sleepless nights, physical pain and mental torture, as well as deprivation of all sorts for his people.

Both these books reveal him hard at work and focused on the job at hand, or thinking about the future of his country and its people. Such commitment and capacity for hard work explain why he worked for different committees at different levels, whether as a youth in Gopalganj, or a student in Kolkata. It is for such a complete commitment that we find him getting involved in Muslim League politics in the city, or becoming a rising politician in post-partition Dhaka. It is for the belief in what he felt was the cause of his people that he went to prison repeatedly.

From Bangabandhu's two published books we learn also of his unceasing reflections on history and about his postcolonial consciousness. He always kept in view the sacrifices made by other Bengali Muslim leaders before him. In The Unfinished Memoirs he writes of "how the British had snatched away power from the Muslims" and how then "the Hindus had flourished at their expense." He is aware too, he tells us in the same section of his narrative, of the Wahabi movement, Titu Mir's rebellion, Haji Shariatullah's Faraizi movement. A little later, he underscores the necessity of breaking free from the clutches of "Hindu moneylenders and zamindars."

Always, Bangabandhu was willing and ready to stand up against men with feudal mindsets, whether they were Hindus or Muslims. In the formation of his consciousness, anti-communal as well as anti-feudal emotions always played a major part, as did his awareness of the negative roles played by such forces in Bengal's history. Bangabandhu's dislike of the callous and superior attitude displayed by feudal and upper class leaders comes out clearly in his narratives when he describes a visit he had to take because Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy had wanted him to convey a request to a Khan Bahadur of Rangpur, who was also an MLA, to come to Kolkata. The young Mujib travelled all night to get to Rangpur. However, hungry, exhausted, as well as sleepy though he was, the young man was not invited in or offered anything by the titled man. This was one of the many moments when the budding leader realised that he would have to take a stand against the heartless Muslim leaders of East and West Pakistan's Muslim League.

The Unfinished Memoirs is thus the story of a spirited young politician learning about how he should take his people forward on the road to independence as he dived deeper and deeper into East Bengal's politics. It is a narrative that is very much about his instinctive identification with ordinary people and a sense that he belonged to them and not in the pockets of distant rulers. In the Prison Dairies, too, we see him reaching out to ordinary people and demonstrating his empathy for prisoners whose status made them much more vulnerable than those who had political "division" to the brutality of the guards. His compassion extends fully even to the mentally ill in prison who would often prevent him from sleeping at night.

Bangabandhu realised early that the real enemies of a country are those who exploit ordinary men and women. In The Unfinished Memoirs, they took the form of Brahmin or Muslim landlords, or moneylenders or businessmen-politicians. In the Prison Diaries, their avatars were the (West) Pakistani politicians and administrators of the period when he was in jail and their Bengali lackeys. These books reveal amply his democratic and secular frame of mind and his attraction for socialism as well as his emerging vision of nationalism. Whether outside prison or inside it, we see him in these two books as someone incapable of being cowed down by the intimidatory tactics deployed by arrogant politicians, hardened bureaucrats, sadistic police personnel or vicious military men.

There are many, many reasons why every educated Bangladeshi should read The Unfinished Memoirs and the Prison Diaries, but surely, the most cogent ones are that we can deduce from them time and again the evolution of Bangabandhu's political philosophy and embrace through his narratives the underlying principles of the Bangladeshi state. Looking at the Muslim League government at work in East Pakistan, Bangabandhu came to understand clearly why governments must be by the people, for the people and of the people, why democracy worked best, and why any government in power should work on democratic assumptions. Reflecting on colluding politicians who served the state purely out of self-interest and uniformed people who worked by incarcerating and oppressing people, he seemed to have learnt more and more the precariousness of freedom and the need to protect it from those who would take it away from the people—again and again.

There are thus many lessons we can learn from The Unfinished Memoirs and the Prison Dairies. For instance, we see in the first book the young Mujib realising by the end of 1950 that the problem with Liaqat Ali Khan was that "he wanted to be the prime minister not of a people but of a party" and "that a country could not be equated with any one political party." The need, he felt then and later, was the need to create a country that worked fully on secular and democratic principles. Imprisoned illegally repeatedly, the young politician declares strongly, "It is wrong to keep anyone in prison without a trial," testifying thus to his firm belief in fundamental human rights.

Coming from Kolkata to a country that was supposed to be completely independent, and therefore a country whose people were supposed to have all kinds of human rights, Bangabandhu was shocked to sense that attempts were underway to deculturise East Pakistan's Muslims, strip them of the "Bengali" part of their identity as far as possible, and make them adopt the Urdu language for state occasions. By early 1948 the young Mujib and fellow members of the Student League had joined other activists in opposing Muslim League moves to make Urdu the only state language of Pakistan, and in demanding that Bengali be made one of the two state languages. Although in jail in February 1952, he was in constant touch with organisers key to the Language Movement. He believed with great conviction that, "no nation can bear any insult directed at its mother tongue."

Throughout The Unfinished Memoirs, Bangabandhu records his love of everything Bengali. He was deeply attached to Bengali culture as a whole and the Bengali language in particular. When he heard Abbasuddin's song in a boat on the Meghna, he tells us that he was simply mesmerised by the beauty of the whole scene. In Karachi a few years later, he is reminded by its setting of how green his beloved Bengal was, and how beautiful, compared to the "pitiless landscape" of the West Pakistan. This makes him compare the hard mindset of West Pakistanis to the softness of the Bengali temperament and makes him conclude, "We were born into a world that abounded in beauty; we loved whatever was beautiful."

Bangabandhu's love of Bengali writers, as well as his secular impulses, is clear in an incident when after Suhrawardy had been pointing out to some West Pakistani lawyers how West Pakistanis had received a distorted picture of the role of Hindus in the Language Movement. Immediately afterwards, they wanted Bangabandhu to recite some of Nazrul's poems. Bangabandhu did so, but as if to show how secular he was, he recited a few lines from Rabindranath's poems as well. In the Peace Conference he attended in China in 1951, he spoke in Bengali, reasoning that since Chinese, Russian and Spanish were being used why he should not speak in Bengali. His growing conviction that autonomy was needed for East Bengal was now linked to his linguistic nationalism.

Bangabandhu had come closer and closer to the view that Bangladeshis needed a country where secularism, socialism, democracy and the kind of nationalism based on upholding the Bengali language and celebrating Bengali culture must take roots. As for the fourth pillar of our 1973 constitution, clearly he felt strongly that inequality in all spheres should be minimised in all fronts. At the end of his description of his visit to China in The Unfinished Memoirs, he says unequivocally: "I myself am no communist; I believe in socialism and not capitalism. Capital is the tool of the oppressor." Analysing the defeat of the Muslim League at the hands of the United Front in 1954, Bangabandhu observes that it was no good to try to fool the people by using religion as an excuse to exploit and dominate others. He notes too that what "the masses wanted is an exploitation-free society and economic and social progress."

The Unfinished Memoirs is thus not only a record of the first thirty-four years of Bangabandhu's life but also a book depicting the evolution of his political thinking. It is also a work telling us that we need to restore the four pillars of the country—nationalism, socialism, democracy and secularism—fully if we are to build the kind of Sonar Bangla that Bangabandhu dreamt of. We must learn from him the courage to speak truth to power, here and everywhere, for nothing should take us away from our founding principles. The Unfinished Memoirs indicates too that we need to readjust our course when we need to. As he says at one point of his book: "When I decide on doing something I go ahead and do it. If I find out I was wrong, I try to correct myself. This is because I know that only doers are capable of making errors; people who never do anything make no mistakes."

Men such as Bangabandhu appear only once in an epoch. However, he has left us Bangladesh, The Unfinished Memoirs, the Prison Diaries and his other writings, speeches and letters so that we can try to achieve his dreams. He himself was not able to realise them because 41 years ago traitors and murderers had assassinated him and killed his family members, trying to change the course of our history. On this day, we should not only pay our respects to his departed soul, but also rededicate ourselves to his vision of Bangladesh. We can then work for his Sonar Bangla, depending at least partly on the legacy he has left for us in his writings and speeches.

Fakrul Alam has retired from the University of Dhaka's English department recently and is now Pro-Vice Chancellor of East West University. He has translated Bangabandhu's Prison Diaries from Bengali.

Comments