The new age demands a re-reading of Bangabandhu

A historic leader, no matter how great or powerful, needs to be discussed, debated, and learnt from—not blindly followed. That goes for Bangabandhu, too. Until recently, saying this out loud would have been tantamount to sacrilege in an environment of total adulation cultivated over the past 15 years. But the sheer, unadulterated disregard shown for the chief architect of our independence soon after the Awami regime's collapse has upended all calculations. Perhaps equally telling has been the relative lack of surprise or even sympathy, at least of the kind you would have expected. All this calls for a re-evaluation of Bangabandhu's legacy in this new era of revolution.

An argument can be made about how much of the anger directed at Bangabandhu's statues and murals on August 5 was really aimed at the man himself. Indeed, during the mayhem that followed Sheikh Hasina's escape, many other monuments and landmarks of historical significance were also attacked. Even the parliament building, Ganabhaban, and the Prime Minister's Office (PMO) were not spared, as mobs swarmed and vandalised them, many making off with furniture, bedding, potted plants, etc.

However, if there was a common target in this outburst of raw emotion, it was the key symbols of power—and what better symbol of it than the personality that Awami League had so unabashedly exploited to assert its supremacy? Many of the estimated 1,220 statues and murals it had erected of him across the country were damaged or pulled down. The historic Mujibnagar Memorial Complex in Meherpur, where he stood tall among other sculpted heroes of the Liberation War, lies in ruins. Even his residence-turned-museum in Dhanmondi was looted and burnt down.

There are various theories about the men behind this vandalism. One involves angry mobs taking it out on anything associated with Awami League. Another involves a vague, and frankly unhelpful, reference to the re-rise of anti-liberation forces. Some observers simply blamed "miscreants" for taking advantage of a fluid security situation. But it's worth recalling that Bangabandhu's murals and statues had been destroyed even during Awami League's iron-fisted rule. This suggests that the latest vandalism was not just a momentary madness—any resentment was long in the making. And the fact that the national holiday on August 15 would be cancelled soon after, in a unanimous decision by the council of advisers and political parties, further represents the shifting ground beneath the once-inviolable stature of Bangabandhu.

How has a man who deserves the highest honour for his role in our independence struggle come to be treated with such disrespect? At the risk of sounding clichéd, let's just say this is what happens when respect is imposed, legislated, and weaponised. Over the years, we have seen how the Awami regime and intelligentsia cultivated blind, unquestioning adulation, suppressing any nuanced and dispassionate study of the man who led a very eventful life.

How has it come to this? How has a man who deserves the highest honour for his role in our independence struggle come to be treated with such disrespect? At the risk of sounding clichéd, let's just say this is what happens when respect is imposed, legislated, and weaponised. Over the years, we have seen how the Awami regime and intelligentsia cultivated blind, unquestioning adulation, suppressing any nuanced and dispassionate study of the man who led a very eventful life.

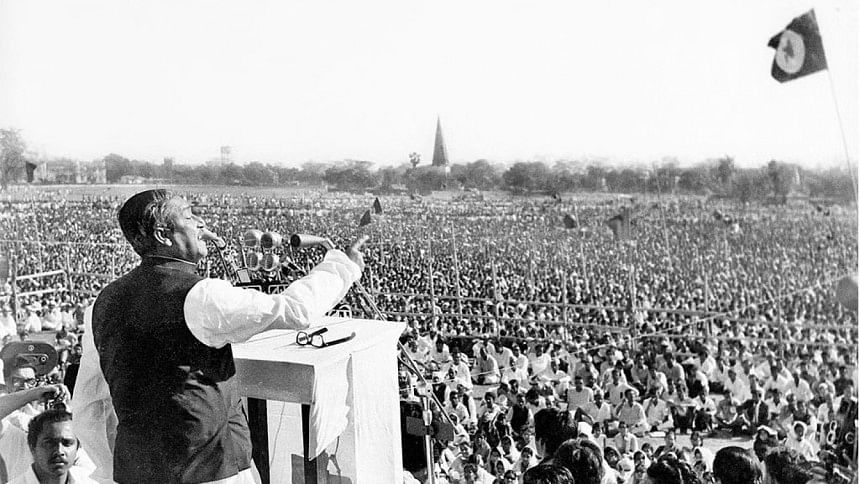

We have seen how the personality cult around him was continually enhanced through an infinite mix of Bangabandhu-themed monuments, billboards, textbooks, notes and coins, postage stamps, etc. His posters were churned out and plastered everywhere, his portraits hung in every government office. From hospitals to universities to safari parks to high-tech centres to bridges and expressways—everything bears his name. His words were turned into catchphrases, his speeches tirelessly rebroadcast on state television. His life spawned innumerable books, shorts, and movies, often through state sponsorship, giving him a saint-like status. And anyone who dared to question it would be silenced through various legal tools.

Even Bangabandhu would have found this deification quite distasteful, had he been alive today.

This is quite unprecedented not just in the subcontinent, but perhaps anywhere in the world. In India, where we saw Congress live off Mahatma Gandhi for decades, he was not subjected to such wholesale deification. In Cuba, you will not see any statues of Fidel Castro. In fact, naming of any street, institution, locality or monument after Castro is prohibited by law. There is then the idolatry encouraged by other communist leaders such as Mao Zedong, Josef Stalin or North Korea's Kim family, but that too may pale in comparison to the ubiquitous presence of Bangabandhu in Bangladesh.

For those of us who grew up in recent decades, Bangabandhu was a story narrated through a carefully orchestrated medley of pictures, historical accounts, audio clips, and video footage. It kept you in awe of the person. It kept you at a distance. We were raised to bow before his altar without really understanding him, and marvel at his greatness without knowing, beyond the highlights of his career, what made him great to his people. He was, for us, not someone we could easily relate to, but one shrouded in reverent mystique.

But the way to approach a great leader is not by ignoring his past deeds or his humanness, but by acknowledging how these helped him become the man he was destined to be. A leader doesn't have to be flawless. Englishmen do not deny that millions of Bangalees starved to death in 1943 when Winston Churchill diverted food to British soldiers and other colonies while a deadly famine swept through Bengal. In China, Mao-bashing is very much a thing. Even though he and his descendants mounted campaigns that developed the country and simultaneously elevated his cult of personality, many associate his legacy with mass murder and violent class struggle. Similarly, many other leaders who led their nations to their most glorious moments had to face the bitter test of time as their legacy was subjected to harsher interpretations—often as an opposite reaction to their deification.

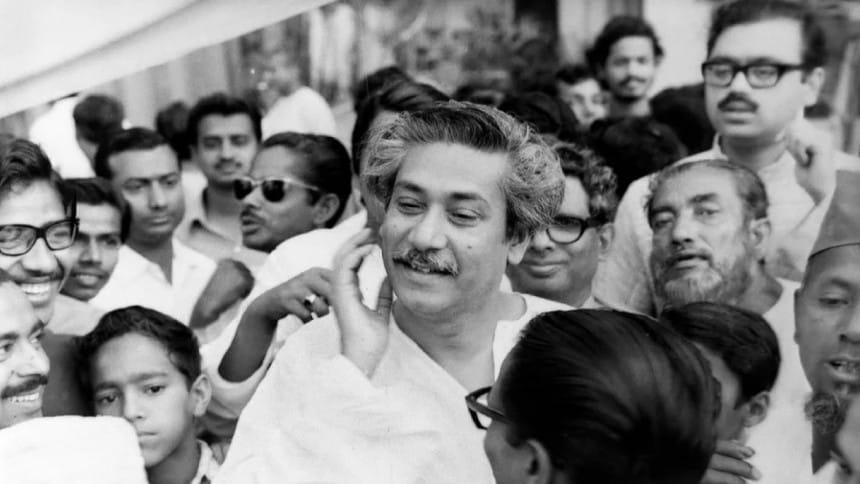

Like many revolutionaries who later became statesmen, Bangabandhu had his fair share of mistakes and failures. Sometimes he learnt from them, sometimes he failed to. Sometimes he made bad judgement calls. Sometimes his decisions distanced him from trusted aides, and even had had the inadvertent effect of isolating the very people he loved and fought for. Those were not his brightest moments—those were his "human" moments. But this is precisely what made him someone the new generation could identify with—a man with human triumphs and failings—yet this is the part that was often buried.

For his part, Bangabandhu was known for his remarkable affinity with the ordinary people. The candour with which he interacted with them is legendary. He commanded their respect, rather than forcing it upon them. However, like many revolutionaries who later became statesmen, Bangabandhu had his fair share of mistakes and failures. Sometimes he learnt from them, sometimes he failed to. Sometimes he made bad judgement calls. Sometimes his decisions distanced him from trusted aides, and even had had the inadvertent effect of isolating the very people he loved and fought for. Those were not his brightest moments—those were his "human" moments. But this is precisely what made him someone the new generation could identify with—a man with human triumphs and failings—yet this is the part that was often buried.

The challenge of the post-truth age is that no legacy is innately secure, and truths in politics are invariably contingent. In post-truth politics, you appeal to emotion rather than objective facts to shape public opinion. Emotion excites the mind and lasts for a while, but for a lasting impact, there is no alternative to a narrative based on facts and truths. Bangabandhu as a subject of study should be approached with an openness to embrace truths, however unflattering.

In the new age of revolution, Bangabandhu can be just Bangabandhu—or Sheikh Saheb, or Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, or simply "Mujib"—without the obsessive, cultist praise following him but also without meaningless criticism along party lines. He may still remain the Father of the Nation, but more human, more relatable, more in alignment with other heroes of our independence. And for that, it is essential that he be restudied and reimagined by subjecting his life and legacy to broader interpretations.

Badiuzzaman Bay is assistant editor at The Daily Star. He can be reached at [email protected]

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments