Reframing water challenges

The logic of averaging "surplus" and "deficit" to optimise and equalise resource allocation is neither new nor actionable. For example, if we were to take the "food surplus" from all regions of the globe and deliver it to households with a "food deficit", no one would go hungry. Yet, over 800 million people remain food insecure and hungry every day. Why does this happen?

Short answer: Politics. This framing of politics, the one promoted by Chanakya (300BC) and Machiavelli (1500AD) and summarised by Lasswell (1936): Politics is - Who gets what, when, and how.

Water is one of the most vital resources for our survival. We need to understand and address how "surplus" and "deficit" plays out within the context of water politics.

The ideas of linking rivers to equalise surplus and deficit of water are not new.

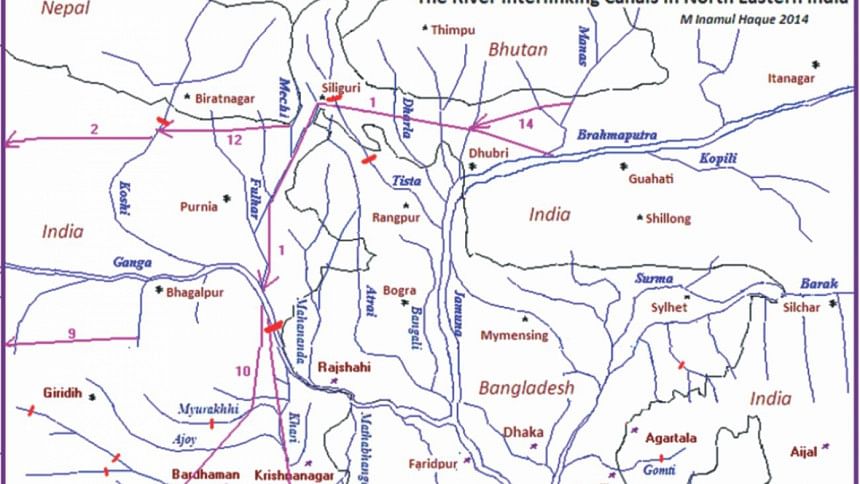

Visveswarya - the legendary engineer of early 1900s - envisioned the idea of connecting rivers in the Indian subcontinent and some of his ideas evolved at a grand scale in the interlinking project framed in the 1980 report from India's Ministry of Water Resources, Indian National Perspective for Water Development. It envisioned linking 14 rivers from the Himalayas and 16 across the India peninsula to bring water from areas of surplus to areas that would benefit from more water.

35 years later: none of the links have been implemented.

Critics argue that interlinking project is neither economically feasible nor environmentally sustainable. Equally important is the lack of technical information about the viability of the project given the cost – US$125 to 200 billion. Beyond a few lines drawn on the map to indicate the rough location of the dams and canals, nothing is available to the professional community to verify the justifiability and efficacy of claimed benefits from the project. Downstream, Bangladesh - which shares 54 transboundary rivers - is worried about the impact these linking projects will have on its people, economy and the environment.

It appears that this Interlinking project – envisioned as a "surplus-deficit" problem with a techno-centric solution – is not only an inaccurate diagnosis of the problem, but also a short-sighted prescriptive solution that is not actionable.

Over the last three decades, the science-policy-politics of water has moved away from techno-centric approaches to more integrated and adaptive management. Globally, there is growing consensus that the complexity of issues as well as the competing and often conflicting values and priorities make the process of charting a path for water security difficult.

A reframing of this interlinking project is urgently needed. The politics of water demand answers: Who decides water for whom; who bears the burden and at what scale?

These difficulties are amplified by practical questions like: How do we resolve water sharing issues when Gujarat demanded that Maharashtra must agree to share more water from Tapi if it wanted more water from the proposed Damanganga-Pinjal link, which will supply water to Mumbai? How can future management meet the previous agreements on the Ganges that allocate water between India and Bangladesh? How does any water agreement among the Himalayan basin countries relate to larger regional concerns beyond water?

These are a small subset of many questions that need to be raised and discussed. More importantly, these questions are contingent upon the context, framing, and choice of the problem's scale. Consequently, there are no pre-specified solutions to these complex problems. As the Water Diplomacy Framework argues, complex problems cannot be solved but can be resolved through a negotiated mutual gains approach, which is essential to chart a sustainable new future for the Himalayan rivers.

The commentator is Director of Water Diplomacy, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Professor of Water Diplomacy at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, USA.

Twitter: @ShafikIslam

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments