Paris Agreement has just come into force

The Paris Agreement (PA) has just taken effect, only eleven months after it was adopted at COP21 of the UNFCCC in Paris last December. This is almost unprecedented in global diplomatic history, particularly for an agreement involving the most intractable global agenda of today – human-induced climate change. After the frustrating experience with the Kyoto Protocol for almost 20 years, this is a refreshing and welcome beginning in climate diplomacy. As we all know, the Paris outcome was dubbed as Paris Agreement, only to allow President Obama to use his executive power to accede to the Agreement, bypassing Congressional ratification. The push came with the US-China initiative to accede to the Agreement in early September 2016, when the two largest emitters of greenhouse gases, one historically the largest and the other, currently the number one emitter.

Others followed suit in quick succession to meet the double trigger provision of its coming into force: ratification by at least 55 parties covering at least 55 percent of global emissions. As of today, 94 countries ratified the PA, covering over 66 percent of global emissions. Now after 30 days of meeting the second threshold, the PA has become a legal instrument.

Tasks at Marrakech

Now the scene is set for the COP21 to be the COP serving as the First Meeting of the Parties to the Agreement (CMA1). This process happened in such haste that the house could not be made ready yet to get in. Thus, an unfinished and long agenda awaits the COP22. Its agenda shows a long list of simultaneous openings of plenary meetings to begin with: the second part of the first session of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Paris Agreement (APA), the body charged with getting the house ready for CMA1, COP22; the twelfth session of the meeting of Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP12) and CMA1, among others.

So the plate is full for the two week-long event beginning on November 7 in the historic city of Marrakech, which is hosting the COP for the second time, after COP7 back in 2001. The big openings will be followed by negotiations in at least 10 tracks, the highest ever in the UNFCCC meetings: adaptation, mitigation, loss & damage, finance, technology, capacity building, transparency, global stock-take, compliance and cooperative approaches. Actually, the primary goal of COP22/CMA1 will be to develop the modalities, procedures and guidelines (MPGs) for operationalising all the negotiation tracks set in Paris. There is also a long list of processes and structures to be operationalised under the PA. These are: an enhanced transparency framework for climate action and support, global stock-take every five years, a 12-member compliance mechanism, a clearing house for risk transfer and insurance, a task force to devise integrated approaches to deal with climate-induced displacement, approval of the 12-member Paris Committee on Capacity Building and adopt a five-year work plan, the Capacity Building Initiative for Transparency, development of modalities for accounting of public climate finance, a new market mechanism and a global sustainable development mechanism. All the MPGs must be completed by COP24 in 2018. Marrakech is basically charged with developing the rule book for implementation of the PA, pre-and-post 2020.

Sticking Points

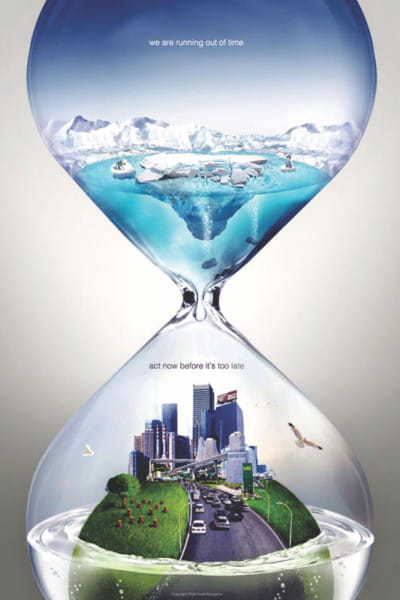

However, development of all these MPG processes may not have smooth sailing. Behind rule fixing, the usual political acrimony characteristic of climate negotiations may raise its head again. As is known, the PA is a legal hybrid - mix of both binding and no-binding elements: the binding elements relate to procedural issues, such as regular communications of nationally-determined contributions (NDCs) and global stocktake every five years, while the substantive elements, such as NDCs to emissions abatement and compliance mechanism is non-binding. There is again a mix of bottom-up and top-down approaches. There will be periodic top-down international reviews of NDCs submitted by parties. So, implementation of the mitigation targets is largely based on top-down peer pressure, without any enforcement mechanism. Already estimates show that even with full implementation of all the submitted NDCs, the world will witness no less than a 3 degrees Celcius rise relative to the pre-industrial level. But the target set in the Agreement is a maximum allowable rise of 2 degrees Celcius, with an aspirational goal of 1.5 degrees Celcius. The question remains whether the goal of stabilising the concentration of greenhouse gases will be achieved just with peer pressure, without any naming and shaming.

The foundational problem is that climate change is beset with malign incentives, with unabated ease of free-riding and gaming. So many disparate and overlapping negotiating blocs, both within the developed and developing countries, populate climate diplomacy, where every group has their pre-conceived notions of norms, fairness and expectations.

Butting Heads

The crux of intractability is the mitigation track. Under the present dispensation, each and every party will claim its actions fair and ambitious compared to others. The developed world, though stipulated to lead in action, will focus more on the top-down review and transparency mechanisms to ensure compliance to submitted NDCs by countries like China and India. The self-differentiation based on self-righteousness in all likelihood will not succeed. For the sake of adoption of a universal agreement, the major emitters from the developing countries agreed in Paris to a truce on differentiation between developed and developing countries as enunciated in the Convention, the parent of the PA, and its provisions reflect this in responsibilities in somewhat attenuated form. But it is likely that the rancor may manifest again, once the honeymoon is over.

So there is no reason to believe we are already in a post-equity world in climate diplomacy. About 12 countries, including India, have submitted their ratification instruments with reservations, keeping the option to leave if other players don't play fair. Between this likely bullfight again among the major emitters from both sides, the LDCs are sandwiched, which have very modest expectations of enhanced support mainly for their adaptation actions with the pledged climate finance, technology and loss and damage mechanisms, and the newly established Paris Capacity Building Committee. In between these maxi- and mini-emitters, there are goodwill alliances, such as Cartagena Group or Climate Vulnerable Forum, which try to mediate, bridge and reach out for consensus. With such a potential train wreck, let us hope that climate negotiations under the universally agreed Agreement will continue remaining on a solid track and stave off the impending and irreversible disasters.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments