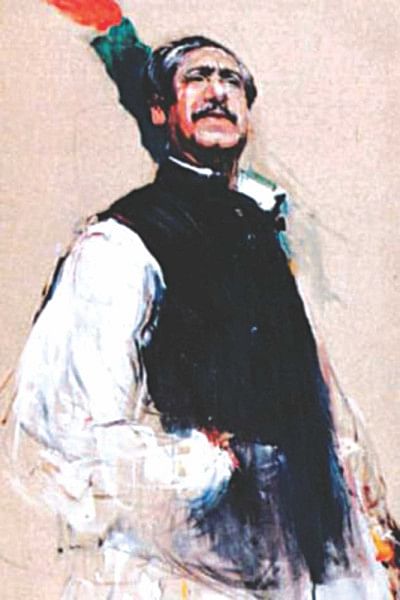

The speech that ignited a revolution

Suhrawardy Udyan, or what was known as Ramna Race Course, has a close relationship with the history of Bangladesh. It was where Bangabandhu, with a sense of passion, a vigour for democracy and an anticipation for change, made the most iconic declaration of his life on March 7, 1971, and subsequently wrote his name into the history books of Bangladesh unlike any before or after him. He showed his political guile, moved people with his captivating voice and in a matter of 19 minutes, went from being the leader of the Awami League to the country's greatest national asset.

The idea of the Pakistan as Sheikh Mujib and many of his colleagues had envisioned in 1947, had remained wholeheartedly unfulfilled. The efforts of the likes of Suhrahawardy or Fazlul Haq in stamping the authority of the Bengali leadership in the national politics of Pakistan had culminated in Mujib's victory in the 1970 parliamentary elections. How could Mujib let his beloved mentor Suhrawardy down? How could he not respond to the increasing wills of his people? The debate whether Bengalis wanted independence or autonomy prior to 7th March is one for the resolution of which historians, not politicians, are required to perform greater research and analysis. But if one is to analyse Bangabandhu's speech, it becomes clear that the search for autonomy was very much enshrined with a subtle, if not vocal, ultimatum for independence. He did not encourage a military conflict, neither did he push the country to the brink of war. But his address is surely indicative of his desire to achieve independence through a peaceful, cooperative and dialogical process. Mujib lit the fire in the hearts of the average Bengali. Yet it was President Yahya Khan's actions and Operation Searchlight which resulted in the grievous nine-month war, and Mujib's address motivated the country into defending itself unequivocally.

In his address to the masses, Bangabandhu acted in the most decent and humane way possible for him. By March 7, he was still unsure about the path his country was to take, and the dillydallying from the Yahya regime only made the situation more difficult. As such, Mujib tackled the question of independence in the most delicate way possible. He referred to himself as the leader of not only East Pakistan but of the majority party of Pakistan. He spoke respectfully of his dialogues with President Yahya Khan and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Mujib's entire argument was based on how, when and why he demanded that the laws and constitutional requirements of the Pakistani state be fulfilled. None of the points he brought forth were utopian or unconstitutional, even in the fragile legal architecture of Pakistan. He demanded the basic democratic rights of lifting martial law, withdrawing military personnel to their barracks, transference of power to elected representatives and an inquiry into the loss of life during the prevailing conflict. In order to protest Yahya Khan's severe violations of democratic rights, Mujib gave several non-cooperation directives. He suggested that government officials and East Pakistani institutions should observe strikes while the people should refrain from paying taxes. None of this explicitly mentioned a call to take up arms. Mujib understood how violent and repressive an armed conflict would become. Henceforth, his pronouncements on March 7 only go to show the gravity, political acumen and wisdom that made him such a great leader. His method of protest and the content of his address puts light on what Pakistan was lacking in its struggle towards democracy, and Mujib should have been a shining example to the entire country. Yet, Yahya Khan faltered terribly on March 25.

This entire country knows the allusive statement: "Our struggle, this time, is a struggle for our freedom. Our struggle, this time, is a struggle for our independence. Joy Bangla!" Even then there are those who question Bangabandhu's personal desire for independence. To suggest that Sheikh Mujib never wanted an independent Bangladesh is inaccurate. The man had fought his entire life for his beloved Bengalis. He had suffered in jail under military autocrats. In the end, his trust towards his own people cost him his life. Yet there are those who question his patriotism. It is indeed quite shameful. In a 1974 article, General Ziaur Rahman wrote about how and why Bangabandhu's 7th March address inspired him, and many like him, to join the liberation struggle. Today, President Rahman's son and many in his party would do well to remember that. It is also a shame that the Awami League deems it appropriate to monopolise Bangabandhu. It is indeed disgraceful that this country fails to have a consensus on the status of a man who single-handedly inspired millions to struggle for this country. It is a humiliation from which we need respite.

There can be debated around the idea of a pre-emptive war versus a defensive war. Debates can arise about when, rather than if, Sheikh Mujib wanted independence. But in no uncertain terms, Bangabandhu did what was best for Bengalis. They were young leaders who were willing to jump into the battlefield and initiate their struggle for independence. On the other side, Sheikh Mujib wanted a political and non-bloody route towards a settlement. On March 7, Sheikh Mujib did a political double. With the last sentence of his address, he gave the de-facto green signal to the young student leaders to prepare for armed conflict if needed be, whilst simultaneously prioritising a non-violent means to end the ensuing crisis. It was a political masterclass from Bangabandhu. But again, it is important to repeat, that historical evidence suggests that Sheikh Mujib did not want mothers to lose their sons in the battlefields, he did not want to leave Bengali children as orphans. He did his best to prevent a war. Which great leader would not? Nevertheless, when it came to it on March 25, he remained resolute and confident, that he may have done enough to spur the vigour which would allow the country to fight back and achieve independence. Sheikh Mujib remained in jail under military supervision throughout the entirety of the nine-month war. But his vision, aims, personality and influence directly guided Bangladesh to victory.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was a patriot. He was undoubtedly the only person capable enough to vociferously inspire the country towards independence. His 7th March speech speaks volumes of the magnanimity and skill he had as a politician. People from all walks of life should not think twice in respecting the man for who he was a visionary, an icon, a leader.

The writer is a third year undergraduate student of Economics and International Relations, University of Toronto.

Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments