Affordable housing: An urban myth or reality?

Mohammad Ali lost his home to river erosion, and was forced to come to Dhaka in search of a better future. He is just another face in the sea of 6.5 million people who have migrated to Dhaka.

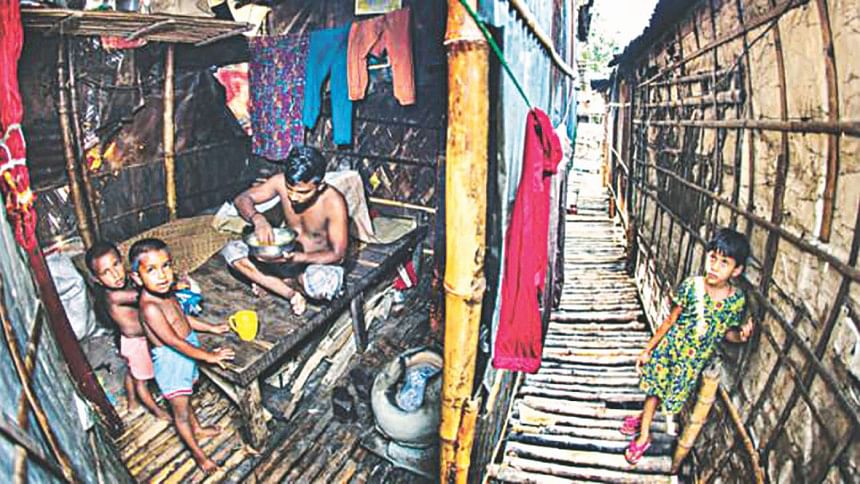

Ali shares a squatter settlement with five other people. As a rickshaw-puller, his average monthly income is Tk 5,000, which places him just above the national poverty line. The rent costs him Tk 3,000 per month. His utilities cost Tk 550 a month, and this excludes food and other living expenses. Ali faces eviction on a regular basis, a reality for 35 percent of people in Dhaka, who currently live in informal settlements.

As Dhaka's population expands, so does its housing crisis. Currently, seven out of 10 households in Bangladesh dwell in conditions that are not permanent. In Dhaka alone, there are over 4,000 informal settlements, or slums, home to 3.5 million people—who form a majority of the urban workforce in the country. Evidently, affordable urban housing is rapidly becoming a primary issue in Bangladesh.

Land is a scarce resource in the country. This scarcity and lack of access to affordable housing compel many to spend over 50 percent of their total income on rent, despite already living on the national poverty line. The exorbitantly high housing costs leave little to spare for food and other basic amenities, adversely impacting the overall wellbeing of the society and exposing families to a dire cycle of poverty.

Urbanisation in Bangladesh is a reflection of current global practices. At present, four billion people (54 percent of the world's population) live in urban centres, while one billion people live in urban slums. This is a significant increase from the turn of the last century, when it was less than 15 percent. In light of ongoing urbanisation, this figure is expected to grow further. The Sustainable Development Goals make specific provisions for the urbanisation phenomenon in "SDG 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable." The New Urban Agenda explicitly highlights the lack of access to affordable housing as a critical factor in urban poverty.

"Housing Policy: Affordable Homes" took centre stage as the theme for this year's World Habitat Day, a global event held by the United Nations on October 2, 2017. The focus on affordable housing recognises its significance as a precondition for tackling inequalities, reducing poverty, and addressing climate change.

In Bangladesh, the housing concern has turned into a full-blown crisis.

Every year, around half a million people migrate to Dhaka from around the country. In order to keep up with this fast-paced population growth, the demand for housing requires introducing 120,000 new units every year. The housing deficit quadrupled in the last decade and, in the absence of adequate measures, the deficit is projected to increase to 8.5 million units by 2021.

What steps have been taken thus far?

Bangladesh has made significant progress in the planning of affordable housing policy. The country is a signatory to the New Urban Agenda, which stipulates that housing is a right and a requirement for realising transformative social change. The government also has a National Housing Policy, which was approved by the cabinet in April 2017 and guarantees housing for every citizen.

The Bangladesh government's 7th Five-Year Plan, which came into effect in 2015, makes specific provisions for affordable urban housing as a policy concern under its national urbanisation strategy. It presents urban housing and poverty reduction strategies, and puts forth some recommendations including creating efficient housing markets, improving financing mechanisms, easing access to land and housing, upgrading existing informal settlements and introducing low-cost rentals.

What next?

Despite the concerns expressed by policymakers in the policy stipulations for low-cost urban housing, its implementation requires further deliberation. A number of challenges hinder the implementation of the policy recommendations, including a weak urban policy environment, lack of institutional capacity, inadequate infrastructure, lack of a comprehensive development plan and, most importantly, for the purpose of our discussion, a lack of coordination among development partners.

Government and non-government institutions, academia and the private sector need to work collaboratively on a common platform, in order to increase the salience of the issue, and innovate and scale affordable, quality housing for low-income groups. Pilot models are already in place; the UNDP, for example, has launched a low-income housing model and so has the National Housing Authority. A local collective constituting BRAC University's architecture department, Alive, a local NGO, and the Asian Coalition of Housing Rights piloted a community-led housing model in Jhenaidah.

Meanwhile, with the aim of opening the window for collaborative discussions, strategic planning and future initiatives related to affordable housing, BRAC's urban development programme is organising a national convention on housing finance for people living in urban poverty on Sunday, October 15, 2017.

Even in their pilot phases, the low-cost housing models mentioned above are exemplary. However, if we are to enable sustainable transformative change, scaling is necessary. Financing these low-cost housing models is an investment towards more sustainable cities for everyone.

The mayors of city corporations and municipalities alike will have to play a bigger role as change makers. They must tackle urban housing challenges and address region-specific problems that arise from rapid urbanisation. A more active role in solving the urban housing crisis is a step towards sustainable living in densely-populated urban centres.

Asif Saleh is the senior director of strategy, communications and empowerment at BRAC.

Comments