Are our millennials shying away from politics?

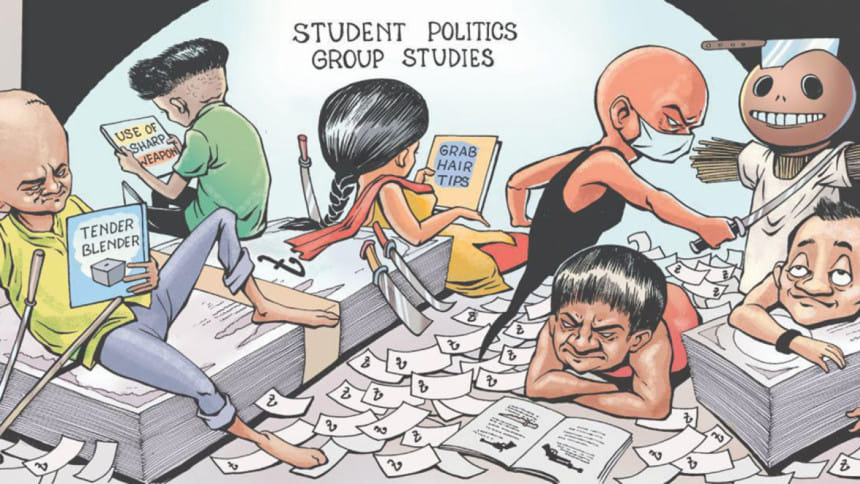

ALTHOUGH tragic, it is understandable why the youth of today, especially those unacquainted with history, find it so difficult to comprehend fully the glorious past of Bangladesh's youth (student) politics. When asked what the first thing is that comes to mind in regard to student politics, many young people will now answer with these words: “violent”, “self-serving”, “self-aggrandising”, “unethical”, “corrupt”, etc. And it's true—that is largely what student politics has turned into nowadays. Nonetheless, what they find so unbelieve is also true—that the history of Bangladesh's youth politics truly is as glorious as it gets.

In fact, many past movements of national significance, which changed the history of this region, began at the university, and were led by university students. Among the most notable of these are the language movement at its peak, the mass upsurge of 1969 against the tyrannical rule of Ayub Khan, the political movement leading up to the Liberation War and the democratic movement against the autocratic rule of General Ershad.

It is through these and other student movements that many of the greatest leaders of this region and its people had emerged. And yet, none of these are common today, nor have been, arguably since the 1990s. But before we look into the domestic causes of this, it is important to mention that student politics in general, globally, has witnessed similar declines in their ethical, moral and mass-organisational capacities and significance during the same time-period.

When looking at it from a national perspective, however, one cannot but come across a dearth of reasons that have led to the decline of student politics in our country—institutional failure is clearly one of them. A perfect example of this is the fact that since Bangladesh's ascent to democracy, the country has witnessed not a single election of the Dhaka University Central Students' Union (DUCSU). One reason for this is most certainly that no student wing of any incumbent political party has ever won the DUCSU election. Which is indicative of an even deeper problem—the lack of political space for anyone categorised as falling anywhere “outside of party politics”, namely, that of the ruling party of the day.

Nonetheless, what is also true is that because of the ability of student politics to influence the direction a nation is headed, students are never handed their platforms on a platter—as evident from the opposition they had faced in the past just in our own country—but have always had to create their own. And it is not that there are no signs of students struggling to establish such platforms today either. The demand of students for DUCSU election this year, including through hunger strikes, indicates that they do realise just how important it is for a student body such as DUCSU (whose responsibility is to ensure the wellbeing of students) to hold election.

Another common argument is that repeated disappointments of the past have discouraged students from seeing politics of any form as a useful means of making positive changes which, again, could be a moot point. That is because despite the failure of our politicians and others to keep the promises to the people during and before the Liberation War, students were motivated enough to again successfully rise up against the dictatorial Ershad regime. And for anyone who knows a bit of history, this should, moreover, be an all too common theme—that freedom and basic human rights, historically, have had to be fought over repeatedly.

However, there is one possible unique challenge that the youth of today are facing as opposed to the 1960s, 70s, 80s and 90s. That is, the overwhelming influence of money in politics. During the glory days of Bangladesh's youth politics, the great leaders that the universities produced were most often willing to serve the people and did much of their work through direct interaction and involvement with the people. Nowadays, however, there seems to be a clear divide between student politicians and ordinary citizens and, at times, their own peers even.

Much of political success, according to Professor Rehman Sobhan, now depend on who can bring the most amount of “money” or “muscle” to the table, rather than on interaction with ordinary people. And whereas this naturally fails to produce the same type of empathy among young politicians for the people they claim to represent, ordinary citizens and students themselves fail to see how student politicians should have any obligation towards them. This disconnect between young people involved in politics and the general populace is, moreover, symptomatic of the general state of politics in our country.

And when one would normally expect student politics to break this cycle of detachment, the cycle of conformity that seems to have firmly taken root is producing none of that—as Professor Sobhan explains, “there were no signs of leadership from the new generation.” And when conformity such as this becomes the norm, is it logical to expect any better than what has taken place? Can conformists lead a nation, particularly in today's world of rapidly changing and continually evolving problems? One would think not.

This environment of conformity further pushes meritorious students aside, depriving the nation of new ideas and thoughts that are essential for it to evolve. Destroying unity among young people and creating further divisions among them as allegiance to political parties now mean more to students than working with their peers to solve common or even larger national problems.

Part of the responsibility for this must fall on the shoulders of a section of university teachers and administrators, as with the unparalleled benefit (monetary and in terms of influence) they now get to derive from being loyal to political parties, the independent working of universities today is all but non-existent. This means that the university is no longer a centre for the free flow of thoughts and ideas that it once used to be.

And because of that, politics no longer instils in students the dream of creating a better future and in fact, has become another glaring example of opportunism—serving the interest only of select groups. Under such circumstances, students from ordinary and well-educated backgrounds can hardly ever participate in university activities, which is becoming more and more evident by the day as parents with any form of ethical beliefs openly discourage their children from participating in student politics.

This can only homogenise student politics in our country even further. And while those who monopolise all positions of influence within youth politics may be celebrating right now, the situation at hand is completely counterproductive for our country and its people looking ahead. Ironically, if we look at history, it is precisely at times like this when great leaders from among the youth population have risen up in the past, time and again. And perhaps that should give us reason to still be hopeful going forward.

As eminent educationist Syed Manzoorul Islam said in an interview with The Daily Star, “A university… is a very strange and interesting place. While many students are going in that direction, quite a few others are taking a different direction…if even one percent students strive to become thought leaders, they can neutralise a much larger percentile looking to become office workers and salary men. So while a large number of students are looking to become government workers or corporate executives, others are preparing themselves to take up [the] challenges of the future.” And it is only the future that “can tell which force will be more important to us.”

Eresh Omar Jamal is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments