Facebook's threats to the social fabric

Former US President Barack Obama has recently joined a growing chorus of critics of social media. In a recent interview with Britain's Prince Harry on a radio show, he warned of the divisive and self-serving use of social media and the Internet, saying that people can have entirely different realities on the virtual platforms. "They can be cocooned in information that reinforces their current biases," he said.

He further explained: "The truth is, on the Internet, everything is simplified, but when you meet people face to face, it turns out it is complicated." Barack Obama is perhaps best positioned to say this because he watched closely, during his last days in office, how fake news and outright hoax were shaping the case for a Trump presidency.

In the days since, there has been a great hue and cry over Facebook's role in spreading fake news. Facebook has subsequently found itself under intense scrutiny by the US lawmakers over its power and influence. As part of the wider investigation into Russian intervention in the US elections, Congress has recently forced Facebook, along with two other tech giants, Twitter and Google, to hand over ads bought by Russians to influence the US voters. However, Chamath Palihapitiya, a former vice-president of user-growth at Facebook, believes that the problem with the popular social networking site goes beyond just Russian ads.

At a Stanford Business School event in November, he argued that this was rather a global problem. "It is eroding the core foundations of how people behave by and between each other," he said. Less than a week before him, Sean Parker, the founding president of Facebook, had revealed that the founders of the website knew that they were exploiting "a vulnerability in human psychology." Both of them seemed to identify the "like" (or reaction, as it is called lately) button as a powerful tool to exploit that vulnerability. They described it as a "feedback loop" driven by dopamine and credited it for Facebook's exponential growth.

Both of them seemed to feel remorse for having helped create and make this Frankenstein grow stronger. There also seemed to be a consensus between them about Facebook's effects on society. "The short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops that we have created are destroying how society works," Palihapitiya said. To Sean Parker, "It literally changes your relationship with society, with each other. It probably interferes with productivity in weird ways. God only knows what it's doing to our children's brains."

Sean Parker and Chamath Palihapitiya have had exclusive knowledge of how Facebook worked. That is precisely why we should take their testimonies very seriously, which stand in stark contrast to the visions of Mark Zuckerberg, the co-founder and CEO of Facebook.

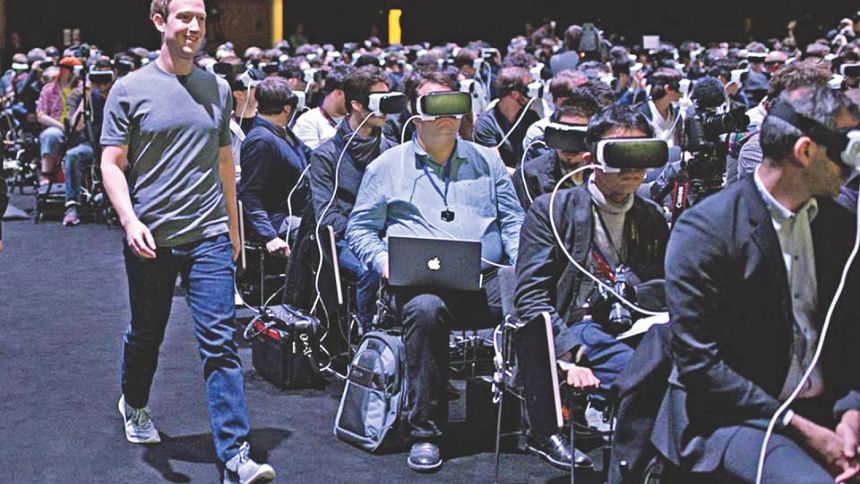

In February last year, Zuckerberg published his manifesto for humanity in a lengthy Facebook note, in which he outlined his plan to build "a global community" based on the website he had created. The prospect that Zuckerberg's global community will be run by a corporate entity that is hungry for profits, unregulated, and, for small countries like us, unanswerable, should terrify us all. The insight that Parker and Palihapitiya provided us has enabled us to analyse Zuckerberg's vision from a different perspective.

Facebook's global community, Zuckerberg says, will be supportive, safe, informed, civically engaged, and inclusive. But, according to Palihapitiya, Facebook has so far resulted in the absence of civil discourse and cooperation, mistruth, and misinformation.

Once responsible for boosting the number of users of Facebook, Palihapitiya reveals that the tools that he had created for that purpose are "ripping apart the social fabric." Therefore, when Zuckerberg says he wants to strengthen the social fabric, we should be wary of his motives and the motives of those behind him.

In his manifesto, Zuckerberg sought to replace traditional social groups, which collectively form the social fabric, with a virtual global community. For one, Zuckerberg cited declining membership in social groups to argue that these groups can be revitalised virtually on Facebook. He cited plenty of examples to show that the virtual community has the potential to deliver what social groups in real life once did but now cannot. In other words, he wants us to further reduce the time we spend in interacting with ourselves face to face. Zuckerberg forgets to mention that the declining membership in traditional social groups can be attributed to the rise of social media, especially Facebook. Further strengthening the virtual society may, therefore, mean a further weakening of the traditional social fabric.

It is fair to say that Facebook facilitates the dissemination of information, helping people solve their problems by closing or reducing the information gap. Facebook's power to disseminate information, however, has been exploited to spread misinformation. While Zuckerberg argues that his brainchild project seeks to bring people together, he admitted that it was also used to divide people. By saying so, he probably referred to misinformation, fake news and hoax that spread through Facebook. But he refuses to acknowledge that Facebook did more to divide people than unite, because admitting so would be inconsistent with the very business model of Facebook. It will be naïve to expect Facebook to revise its survival mechanisms or fundamental strategy that only seek to attract and make users spend more time on the platform.

That is why, we need to be wary of Facebook and other tech companies whose works profoundly affect the way society functions. We need to do everything we can to allow traditional social systems and platforms to function vigorously, and make sure that the virtual community never takes precedence over the health of our social fabric.

Nazmul Ahasan is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Comments