AGAINST ALL ODDS

On the occasion of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science on February 11, Star Weekend profiled several prominent female scientists who have risen to the top of their respective fields in Bangladesh. Their scientific contributions and accomplishments over the years have been in sectors crucial to Bangladesh's development, from identifying the jute genome to preventing cholera outbreaks. Young girls who wish to study science have able and flourishing role models in these five female scientists, among others, who have reached the top despite numerous challenges.

For young girls interested in pursuing an education in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields and young women scientists just starting out in their careers, these five women scientists and their career paths set an inspiring example.

DR FIRDAUSI QADRI

At the forefront of immunology and vaccine science

Dr Firdausi Qadri has been a major player in improving public health in the country, through her work at ICDDR,B. The organisation is at the forefront of combating infectious diseases such as cholera, typhoid and rota virus diarrhea among others. "I always wanted to do lots of things, but I never expected to do so much in return," she says modestly.

Emeritus Scientist and Acting Senior Director of the Infectious Diseases Division at International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B), Dr Firdausi Qadri was the first Bangladeshi and the first woman to receive the prestigious Christophe & Rodolphe Mérieux Foundation Prize from the French Academy of Sciences in 2012.

Cholera is still widely prevalent, especially at this time of the year (starting from the months of March and April), in high-risk populations such as urban slums. Dense living conditions and lack of clean water and sanitation facilities can cause the disease, says Dr Qadri. "With the oral cholera vaccine, we are trying to prevent cholera outbreaks and hospitalisation due to cholera." Cholera vaccine is not in the routine immunisation programme of the country as of yet.

While Dr Qadri and her team were still deciding, in discussion with the government and international agencies, how best to vaccinate "hot spots" such as urban slums, a million Rohingya refugees were pouring into Bangladesh last year. The refugee camps were primed for a cholera outbreak with packed living quarters, poor water quality and lack of nutritious food.

"The government requested the oral cholera vaccine from the global stockpile and was immediately provided with 900,000 doses to avert a potential humanitarian crisis," says Dr Qadri. These were administered in less than 10 days. "It was pre-emptive vaccination, before an outbreak," says Dr Qadri of the move. Since then, there have been no outbreaks of cholera nor a concentrated outbreak as feared.

Dr Qadri also works on mentoring young scientists. This, she says, is because of a gap of leading scientists between those of her age and younger scientists starting out in the field. "Working in science requires hard work and commitment, especially for girls who face so many challenges," she says.

For family and financial reasons, young women scientists in particular often do not continue their research after their PhDs. At ICDDR,B, Dr Qadri is trying to change this by creating the Young Scientists Development Initiative (YSDI). Here, she mentors several young scientists from each major research division which includes helping identify funding and further training opportunities.

"I would like more women to start thinking of a career in science. If I have done it, you can also do it."

DR HASEENA KHAN

Uncovering the jute genome

The youngest of her family, Dr Haseena Khan was inspired by her older brothers, most of whom went into science and engineering fields. "At the time [mid-1970s], there were many exciting developments in the field of biochemistry. One of my brothers inspired me by describing how these findings had universal implications," remembers Dr Khan, Professor of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Dhaka since 1995.

"I had disappointed my father by not studying medicine. So, I wanted to do something that would make him happy and knew about his love for jute," says Dr Khan. But he had died by the time she had made her decision. She went on to specialise in studying the molecular biology of jute, on which there was little to no work done at the time.

Bangladesh is the second-largest producer of jute in the world and the fibre, as Dr Khan. But working with jute provides unique challenges—it is both cross-incompatible and recalcitrant to tissue culture—meaning it is difficult to cross-breed and manipulate in vitro. Thus, genetic transformation is the only way to improve certain attributes such as low temperature tolerance so that jute can be grown year-round. "I've been able to put genes into jute and have transformed the plant," says Dr Khan who counts genetically transforming jute as one of the greatest achievements of her career.

By the 1990s, Dr Khan had also started identifying the jute genomes and that led ultimately to the Jute Genome Sequencing Project. The project, of which Dr Khan was one of the team leaders, received national and international acclaim in 2010 after the Prime Minister announced that the genome of two local types of jute had been decoded.

Her other work in the field includes reducing lignin content in jute by as much as 25 percent which has significant applications in use as a textile fibre, in paper production, and as bio fuel.

Her work has not been without a cost. "That I have only one child is because of my research work." Working as she did with hazardous chemicals, another child was not an option for Dr Khan. In addition, juggling long hours in the lab and little time off meant that she was not able to give as much time to her daughter as she would have liked."One day, I had to go pick up my daughter from school (usually her father did it) and her friends exclaimed to her daughter, 'Oh, you have a mother!'"

Dr Khan continues to work on cutting-edgemolecular biology, currently working on the microorganisms found within the jute plant, some of which she found have anti-cancer and anti-malarial properties. For the past five years, Dr Khan has been working on the exciting possibilities these microorganisms present.

For girls interested in science, Dr Khan thinks they should not think twice as they make particularly good researchers in her experience. "Seeing something you have worked on develop bit by bit is very rewarding."

DR RUBHANA RAQIB

Three patents to her name

A passion to pursue science is often nurtured in the classroom. "Our teachers were so good that I enjoyed it [biochemistry] very much. They inspired us to go into research and discover new things," says Dr Raqib, Senior Scientist of the Infectious Diseases Division. Dr Raqib's thesis supervisor had been Dr Qadri, whom she subsequently followed into ICDDR,B. She has been at the organisation since 1988.

Dr Raqib has two global patents to her name. Along with then-director of ICDDR,B, Dr David Sack, she invented a new diagnostic method for tuberculosis (TB), called ALS, in 2011 which was patented in the US Previously, diagnosing TB with serum samples led to numerous false positive identification even in those who did not have active TB. They instead developed a test with cultured lymphocytes from blood samples, which successfully identified adult patients with active TB.

Collaborating with Swedish researchers, Dr Raqib also discovered a strategy to use compounds (by-products of food or repurposed drugs) which boosts the body's immune system, by stimulating the white blood cells. This could be used to treat infections in lieu of antibiotics and would not develop resistance, for example.

"Science is rigorous," she says. The time commitment that a career in science requires often proves a stumbling block for many young women even now, who tend to drop out after starting a family or at the very least, slow down. When Dr Raqib was undertaking her PhD studies in Sweden, she left her son with her mother for months at a time while she was away. "Family support is crucial."

A support system is needed—for example, ICDDR,B now has daycare facilities. "In my time, I had to go home during the day to breast feed and see my child," says Dr Raqib. Scientific research is a competitive field and a female scientist is at a disadvantage, while balancing work and family, compared to her male counterpart when it comes to making a mark.

Dr Raqib is now working on the effects of arsenic on health. Arsenic contamination in water and crops is of major public health concern and Dr Raqib and her team was able to show that even low levels of arsenic can signify severe consequences for our health and that adverse effects of arsenic can be mitigated through food-based approaches.

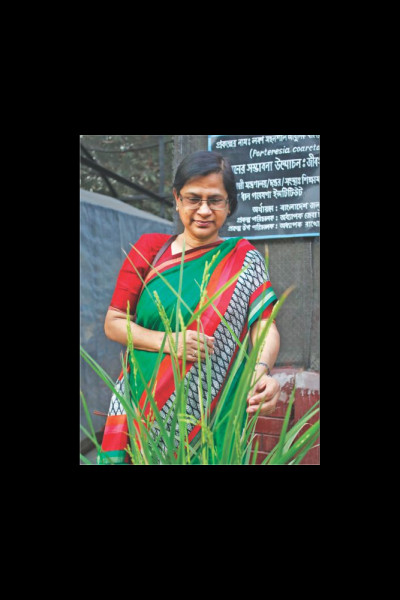

DR ZEBA ISLAM SERAJ

Breakthroughs in salinity tolerance in rice

Rising salinity in the crop lands, particularly in coastal areas, has been a major consequence of climate change in Bangladesh. Dr Zeba Islam Seraj, Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at University of Dhaka, has been working on improving salinity tolerance in rice. Working often in collaboration with the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute, she managed to develop transgenic rice varieties (containing the artificially inserted helicase gene) which would have greater salt tolerance and higher yields.

Dr Seraj is also currently studying a wild rice (known locally as uridhan) which grows in seawater. She and her team are attempting to isolate and clone the salt-tolerant genes into sensitive rice (which cannot grow in high-salinity water).

Nurturing an interest in science in children is a passion of hers, starting with her own daughters. "I would buy them science books and encourage them to do small experiments up on the roof or on the stairs," says Dr Seraj. She believes such steps fostered a natural curiosity and a liking for science in them. She shows me a book she has edited, based on the standard grade six science book, which is designed to make science fun for young students.

While working painstakingly at the molecular level, young researchers often lose grasp of the change they are working towards. Dr Seraj has a net house in the grounds of Curzon Hall where her department is located. "One day, recently, I noticed that the tree leaves look differently and brought my students to observe the changes. They work there regularly but hadn't noticed the small changes—that the leaves growing were healthier, broader." The effects of their genetic work were blooming in front of their eyes.

Scientific research does not always lead to noticeable outcomes and quick payoffs and day to day research can often be a struggle. "Persistence is the number one quality needed for scientists," says Dr Seraj.

DR SHAMIMA K CHOUDHURY

Advocate for women in science

Women tend to gravitate towards the biological and medical sciences, leaving very few in Math and Physics for example. "In our time [she studied at DU starting in 1967], there were very few girls in Physics," said Dr Choudhury, as such subjects were considered "too difficult for girls".

Dr Choudhury, Professor of Physics at DU, remembers facing discrimination because of her gender during her studies at DU. "Several male professors refused to supervise my thesis simply because they didn't take on female students," she says. This ingrained sexism, if not a barrier to entry, can discourage women from continuing in the field. Dr Choudhury found in her research that women with science or engineering degrees opt into other fields of study in the transition to graduate studies.

Alongside her work as a physicist, Dr Choudhury has been a strong voice for women in science throughout her career. "Often, I was the only woman at the table," she says of numerous workshops, conferences and department meetings she has attended in a career spanning 42 years. She has organised mentor-mentee workshops for young women scientists by top women scientists from home and abroad.

"One has to have a role model—the two most influential role models of mine have been Dr Veronica James, my supervisor at New South Wales, Australia, and the late Dr Louise Johnson, Professor of Molecular Biology at Oxford where I did my post-doctoral degree." Now retired from teaching, Dr Choudhury continues to mentor and supervise her students.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments