Auschwitz: Reflections and Realisations

Neat rows of red-brick buildings, bathed in brilliant sunlight, stretched out under an azure sky. The carefully manicured grounds, and the forest beyond, were a lush green. One could be forgiven for mistaking it for a well-run summer camp. It certainly did not look anything like what had been portrayed in Schindler's List or the myriad of Holocaust literature. Even the wrought-iron sign above the gates reading Arbeit Macht Frei (Work Makes You Free) felt distinctly positive—a slogan that one would imagine calling to economic progress and unity. Until your eyes fell upon the miles of barbed wire encasing the beautiful surrounds. You were then immediately reminded of the site's dark past. That the sun could shine on a place with such sombre roots felt very wrong.

Over the next several hours, as I toured the Auschwitz-Birkenau sites, I grappled with similar turbid emotions. After a lifetime of reading about the camps and watching Holocaust movies, I was eager to visit this crucial part of history. It was as I was heading towards Oświęcim that I first realised that my visit to Auschwitz would be a conflicting and challenging experience. Over 70 years ago, people would desperately avoid boarding a vehicle heading to Auschwitz, and today people like me bound up the steps to witness the remnants of a terrible past. It felt wrong.

I made my way around the museum, taking in the execution wall, still riddled with bullet holes, the cans of Zyklon B poison used in the gas chambers, the confronting photographs of prisoners and the jarring displays of their belongings. Amidst all the remnants of these horrors, there, tucked behind a block of buildings in Auschwitz I, was a swimming pool. A guide informed me, in barely disguised outrage, that it was symbolic of the propaganda pushed to the outside world—that the camps were a happy place with recreational activities aplenty. I took several photos of each of these, but every time I lifted the camera to shoot, I wondered if I was disrespecting the victims and diminishing the enormity of the event by confining the experience to a handful of images. It felt wrong.

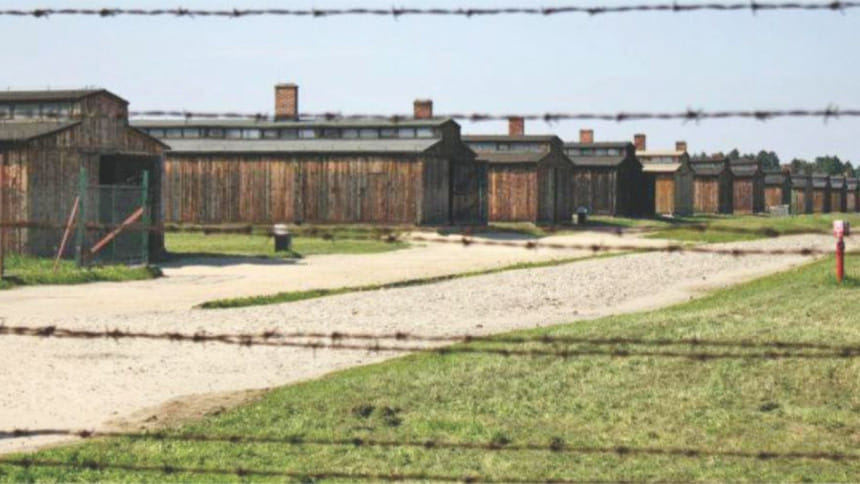

At Birkenau, built specifically as a death camp, I was struck by the vast expanse of the plain. The 175-hectare site housed 300 crudely constructed wooden barracks. The sweeping vista was marred only by the charred remnants of a crematorium and some barracks. As I imagined the sheer scale of the operation, I couldn't help but admire Nazi efficiency, as cold-blooded as it was. It felt wrong.

The existing barracks had been left as they were—cramped, draughty and foul. As had been the gas chamber, where 700 prisoners would be gassed at a time—bleak and sterile. I walked through them all, past a cattle truck perched on the rail tracks that penetrated deep inside Birkenau, till I reached the end of the track. I looked back and could distinctly make out the infamous gates of Birkenau, shining like a beacon over the immense camp. I tried to imagine what it would have been like to have made that journey and lived in such deplorable conditions. I was trying to picture something that many have tried desperately to forget. It felt wrong.

Despite my excitement to be able to visit a place I had read so much about, it was not an easy visit at all. Nor has this article been an easy exercise in writing. As I try and collect my thoughts, I am overcome by a sense of doom, an almost palpable feeling of heaviness. I suppose this is the feeling that JK Rowling speaks of when describing the presence of Dementors in her Harry Potter books.

I've read that visitors to Auschwitz leave overwhelmed. From eavesdropping on the hushed conversations around me, there was at least a single aspect of Auschwitz that left them crushed and questioning humanity. Some were devastated by the scale of the operations; some could not bring themselves to look at the sheared-off hair of the inmates on display. For me, it was a solitary prosthetic leg, protruding from a teetering pile of crutches and other prosthetic limbs that brought home the madness that was the Holocaust. How depraved did one have to be to take away the prosthetics of so many innocents?

And as I draw on my memories to write this piece, I am once again overcome by a crushing sense of foreboding. I think of what is happening in Syria and in our own backyard with the Rohingya crisis, and of our own genocide in 1971. Looking at a photo of a plaque in Auschwitz, etched with Santayana's famed maxim, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it," I find myself thinking—we haven't learnt anything from history at all.

Comments