Making private universities more affordable

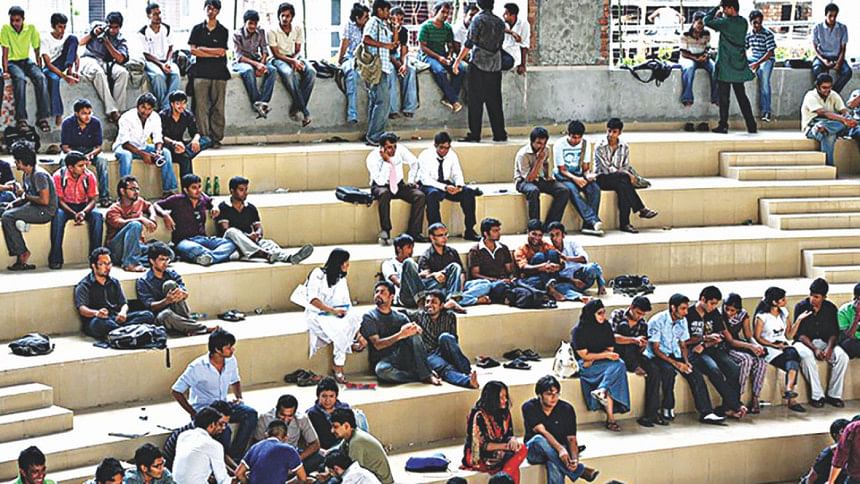

Education remains the cornerstone of success for societies around the world—with the recent quota movement in Bangladesh showcasing some of the ensuing tensions between various stakeholders within our growing economy. Intertwined with increasing youth unemployment numbers, the lack of access to tertiary education, or more specifically the lack of affordability of private education, is a cause of concern for this country. Nevertheless, putting the burden solely on the state to alleviate youth-related problems in Bangladesh is implausible—and as such, our private sector within the education industry must be expected to play a more feasible role in ensuring sustainable human capital growth in the country. The responsibility of the state in this regard is to institute policies which refrain private actors from exploiting low income students.

The BNP led government in the early 1990s took an important step in liberalising the tertiary education industry with the passage of the Private University Act 1992. In theory, the aim of depoliticising education above and beyond the bureaucratic red-tape of public institutions, has boded well for citizens in this country—but it is equally important to note that, to a large extent, it has benefitted the wealthiest of the wealthy in Bangladesh. Ironically, whilst increases in private university numbers have created external benefits in the form of increased nominal spending in the education sector, diversified innovation and more graduates each year, we have witnessed an increasing urban-rural divide and post-graduation youth unemployment take centre stage. Therefore, to internalise the notion that all is well, would be a dent to the very ideals of a free, progressive and equitable Bangladesh that we dream of each day.

The barrier to access private university services is wholeheartedly dependent upon the cost structure—but if tuition costs are brought down to the levels of public universities, there remains little to no financial motive for entrepreneurs to invest in private education. Therefore, solutions must be found from within the existing structure itself. Finance Minister AMA Muhith has come under the scanner for his hasty comments on private universities in the recent years—but the veteran Cabinet member did point out two important things. For one, students acquiring the services of private universities tend to be financially better off than those acquiring public education. Secondly, the brunt of a 7.5 percent imposition of VAT on private university tuition will affect upper to middle class citizens, more than those in the lower stratums of society—an indirect progressive tax, one could say. However, the Finance Minister in simple words, may have had the right idea, but a controversial implementation scheme. In my opinion, a configuration of incentives between private universities and students may be a better approach to ensure increased accessibility to private education, which in turn would help to control tuition increases in the country.

Student borrowing facilities provided by the government, amalgamated with a tuition cap on private education, is seen by many, as a plausible policy mechanism to ensure the simultaneous viability for private universities to prosper and an equitable level of tuition for lower-middle income students. Essentially, as is the case with countries like Canada, the government is expected to provide zero to low interest loans to students who fall below a certain income bracket, to support the youth in their quest to receive quality education. It is a simple, yet effective tool which has spearheaded countries like Canada to the top of the tertiary education system globally. The idea is, that more students receive affordable education, and are able to reinvest the borrowed tuition to the state in the future, whilst at the same time participate in the human capital growth process within the country.

The tuition cap idea is somewhat more controversial, in the sense, that as a regulatory architecture, it is aimed at stopping private sector individuals from solely targeting profit maximisation—a move which may deter some investors in the education industry. But, it is important to remember that tertiary education is indeed a merit good, and it falls within the responsibility of the state to regulate it, in order to ensure efficient results. Rather than imposing a VAT on tuition, which is likely to be passed on to students, a tuition cap institutes an upper limit for private universities to charge their students—in this way, the government is able to address the increasing rate of inflation in the country, with the increasing cost of tuition, and ensure that the net negative effect of tuition increases on students, remains negligible.

The idea of a tuition cap and student borrowing means have been developed in many countries around the world, in order to bring people of all stratums of societies into mainstream academia. Yes, Bangladesh has over 90 private universities. Yes, Bangladesh has over 30 public universities. And yes, the Bangladesh Government is indeed prioritising education more than ever before. Nevertheless, if we keep tertiary education limited to the few and not the many, then it is impossible for market forces to correct the excess demand for education from the 160 million strong population. Targeted policy schemes such as tuition caps and student borrowing facilities are not detrimental to the consumers of education services—rather act as incentives for people to enrol in tertiary education. Unless and until our country prioritises the eradication of the unequal nature of our education system, then the problems of capital flight, youth unemployment and backward rural populations will persist. Therefore, the government has a responsibility to consider its options, and in all honesty, do what it must, to increase the quality and quantity of education—not simply through its own public resources, but through the construction of equitable regulatory policies to support and sustain the growing demand for tertiary education in the country.

Mir Aftabuddin Ahmed is a student of economics and international relations, University of Toronto.

Email: [email protected]

Comments