COUNTER-TERRORISM STRATEGY: An Alternative Proposal

Although the concept of confront-terrorism and related strategies have a long global history, the attack at the Holey Artisan Café on July 1, 2016 made counter-terrorism (CT) a topic of public discourse in Bangladesh. The country saw a rise of militancy in 2005 and a series of attacks since 2013, both of which engendered discussions among security professionals, analysts, academics and policymakers about the ways and means of countering terrorism. Yet, the term CT was hardly a topic of public conversation until July 2016. Despite these conversations, a clear conception regarding the meaning, nature and scope of CT is sorely lacking. In public perception, security operations have become synonymous with CT, except for brief references to "other" measures. Rarely are these "other measures" explained.

Discussions on CT measures have for decades identified two approaches to countering terrorism: the hard approach and the soft approach. The "hard" approach focuses on kinetic measures, that is largely security operations featuring the use of force, intelligence and surveillance, as well as killing, capturing or detaining terrorists. The "soft" approach, on the other hand, encapsulating a range of non-coercive tools and programmes, seeks to understand and address the process of radicalisation and involves the community. Although these two have been in the toolkit of the policymakers for decades, states have demonstrated a proclivity towards the hard approach.

In recent years, analysts have further disaggregated these approaches into three: the tactical, the operational, and the strategic. According to Rohan Gunaratna, "Tactical and operational counter-terrorism focus on kinetic and reactive means to kill and apprehend terrorists and disrupt their operations. Conversely, strategic counter-terrorism, alternately referred to as countering violent extremism (CVE), is both preventive and corrective. Overall, strategic counter-terrorism aims to counter the threat of terrorism emanating from group members and supporters through (a) community engagement to build social resilience and counter extremism, and (b) rehabilitation and reintegration to de-radicalise terrorists and extremists."

Approaches towards terrorism determine the models of counter-terrorism. To some extent, drawing on the hard and soft dichotomy, two overarching models of CT have been in use: the Criminal Justice Model (CJM) and the War Model (WM). The CJM considers terrorism as a crime, and penalisation of the perpetrators within the legal and constitutional boundaries remains the principal mode of responding to terrorism. The CJM prioritises democratic principles as the premise of any actions. The proponents of this approach acknowledge that it may reduce the effectiveness of CT measures, but argue that by portraying the terrorists as criminals, the state denies them the publicity and claim to righteousness the terrorists desire. The WM, on the other hand, considers that the terrorists have waged a war and are therefore met with a similar response. In case of the latter, the onus for response is placed on the security apparatuses, including the military.

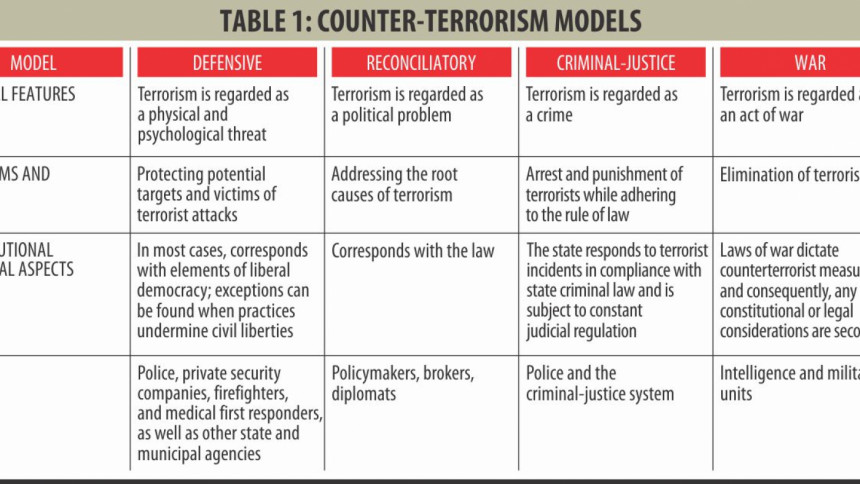

With the experience of dealing with various kinds of terrorism and extremist groups, governments around the world made adjustments to these models. This led to the emergence of two other models of CT: defensive and reconciliatory. Ami Pedahzur, in his study entitled The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism, explains these four models (Table 1).

The most important development in regard to a global response came on September 8, 2006, when the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy. It is considered "a unique global instrument to enhance national, regional and international efforts to counter terrorism." The strategy does not offer a specific model but provides four pillars which are expected to serve as the foundations of any counter-terrorism models of the member-countries. These are: (Pillar 1) Addressing the conditions conducive to the spread of terrorism; (Pillar 2) Measures to prevent and combat terrorism; (Pillar 3) Measures to build states' capacity to prevent and combat terrorism and to strengthen the role of the United Nations system in that regard; and (Pillar 4) Measures to ensure respect for human rights for all and the rule of law as the fundamental basis for the fight against terrorism.

The importance of this strategy is its comprehensive nature which underscores both kinetic and preventive elements of CT strategy within the broad frame of protecting human rights, an issue that has not only undermined various CT efforts but also has provided fodder to the transitional terrorist groups in the past decade. One can hardly ignore that the pictures of torture by US forces in Abu Ghraib helped recruitment of transnational terrorist groups. Similar kinds of actions by other countries have resulted in strengthening the appeal of the terrorists.

The challenges that terrorism presents, the evolving nature of national and transnational terrorist groups, the efficacy of various models of CT, and the experience of the past decades of various countries make it evident that there is a need to balance the hard and soft measures; in other words, achieving balance between security measures and preventive actions is imperative for an effective counter-terrorism model. These must remain committed to both human rights issues and the rule of law. With these in mind, I suggest a comprehensive CT model which include measures within three broad realms: counter-radicalisation, law enforcement and security (Table 2).

An important feature of the proposed strategy is the implicit hierarchy of pre-emption, law enforcement, and kinetic measures. These will help in confronting the menace of terrorism in the long term instead of looking for a quick fix. Addressing the drivers and enabling environments; disseminating a counter-narrative through engagement with the narratives of the terrorists, instead of completely disregarding their arguments; and the inclusion of civil society as a partner are essential in this strategy. Partisan political gains should not triumph the national security interests, neither should they be used to spread a culture of fear. Distinct and independent entities, open to public scrutiny, should lead each of the segments with coordination through an overarching body with power to suggest required policy measures to political leadership keeping national security, human rights and rule of law as their guiding principles. Absence of these guiding principles makes actions suspect and rather counterproductive.

Ali Riaz is a distinguished professor of political science at the Illinois State University, USA.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments