A Palace on the River: Ahsan Manzil

To visit Ahsan Manzil (construction: 1859–1872; historic preservation: 1985–1989; inauguration: as a museum 1992) is to learn the colonial-era history of Dhaka. The 5.5-acre premises of this palace remain today as an architectural reminder of the elite life of the Nawabs of Dhaka during the heyday of the British Raj in the 19th and early-20th centuries. Nawab Khwaja Abdul Ghani (1813–1896), the patriarch of the Nawab family, built the family's official residence and zamindar office—Ahsan Manzil—in 1872 on the bank of the River Buriganga in Old Dhaka (Landowners were known in Bengal as zamindars, the Persian nomenclature.) He named the palace after his son, Nawab Khwaja Ahsanullah (1846–1901).

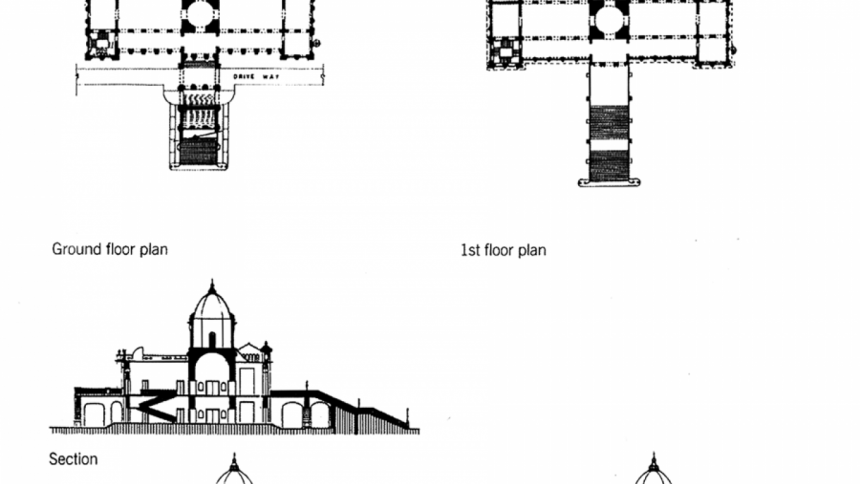

Ahsan Manzil is ostentatiously European in its architectural expression, even though the building's recessed verandahs may recall the Mughal treatment of buildings in a tropical climate. Its triple-arched portal, temple façade capped by a pediment, Greco-Roman column capitals, pilasters, and arched windows—all suggest that it is mostly a European-style building, meshed with some decorative Indian motifs. The palace's soaring dome appears to be more about impressing the viewer on the exterior, rather than within the interior.

Why did the Nawab embrace a European architectural style for his palace? Prior to the advent of British colonial rule, local elites emulated Mughal architecture as their preferred building style, particularly for religious buildings. Charles D'Oyly, the Collector of Dhaka, documented Mughal influence on local buildings with much romance in his book, Antiquities of Dacca, published in the early-19th century. However, with increasing British colonial footprints in India, building design began to reflect the influence of European styles from the last quarter of the 18th century. Many zamindars began to construct their bungalows in flamboyant European architectural styles to showcase their status, wealth, and power.

Nazimuddin Ahmed wrote in Buildings of the British Raj in Bangladesh (1986): "During the 18th and 19th centuries, the chief interests of the aristocratic feudal lords of the land—familiarly known as zamindars, who often held courtesy titles of 'Rajas' and 'Maharajas'—were not only in European dress, wine, horses and external glamours of life, but also in architectural forms and embellishments avidly emulating the West for their pretentious country houses or palaces. Often these picturesque palaces combined European Renaissance elements with the fading Mughal architectural forms." Nawab Abdul Ghani's Ahsan Manzil is one such example.

Today, within the hyper-congested and cacophonous urban growth of Old Dhaka, it is difficult to imagine how this majestic edifice once dominated the riverfront skyline of Dhaka. Colonial-era dignitaries arrived here by luxury boats and ascended its grand flight of stairs, which led to a colourful vestibule and a domed rotunda on the second floor. Many dignitaries of the British Raj either visited or stayed at the Ahsan Manzil. Lord George Nathaniel Curzon, who took over as Viceroy or Governor General of British India in 1899, came to Dhaka to solicit support for the proposed Partition of Bengal and stayed here as a guest of Nawab Salimullah Bahadur in 1904.

Two years later, another momentous event took place in this palace that had crucial political implications for all of India. Invited by Nawab Salimullah, Muslim leaders from all over the subcontinent congregated at the Durbar Hall of Ahsan Manzil for the 20th Session of the All India Mohammedan Educational Conference in Dhaka, from December 27 to December 29, 1906. Here, on December 30, the All India Muslim League was formed, the party that later spearheaded the creation of Pakistan—a separate homeland for India's Muslims—when the British left the Indian subcontinent in 1947.

Who were the Nawabs of Dhaka? The Khwajas, the forefathers of the Nawabs, migrated to East Bengal—first to Sylhet, then to Dhaka—from Kashmir during the 1730s. When Mughal administration of Dhaka ended in 1843 with the death of Gaziuddin Haider, the last Naib Nazim (Mughal administrator) of the city, the Khwajas took over as the city's "guardians." They occupied important positions as Commissioner of Dhaka Municipality. In 1867, Abdul Ghani became a member of the Viceroy's Council. As Syed Muhammed Taifoor chronicled in Glimpses of Old Dhaka (1956), the Nawab family played crucial roles in the modernisation of the city, particularly in the development of educational systems, healthcare, and urban infrastructure, including the filtered water supply system that served the city population. The Nawabs also patronised culture and supported poets and writers of Urdu and Persian literature. In 1875, Viceroy Thomas Northbrook participated in an evening programme at the Ahsan Manzil, when he came to Dhaka to inaugurate the city's water supply system.

Nawab Abdul Ghani emerged not only as a dynamic leader of his clan, but also as the most influential zamindar in the entire East Bengal region in the second half of the 19th century. He fortified the family's powerbase by collaborating with the colonial administration. Sir Percival Griffiths, who was appointed Chief Manager of the Dacca Nawab Estate in 1929, wrote in his book Vignettes of India (1985): "Abdul Ghani and the Moslems of East Bengal stood firmly by the Raj during the Indian Mutiny, and for his services, Abdul Ghani was not only Knighted, but also had the title of Nawab conferred upon him. He was made a Nawab in 1875 (and this title was made hereditary in 1877 for the eldest male member of the line) and Nawab Bahadur in 1892." In exchange for his support of the colonial rulers, Abdul Ghani received many political favours. In 1861, he was appointed as an honorary magistrate; in 1866, he became a member of the Bengal Legislative Council; and in 1867, he was a member of the Viceroy's Council.

Nawab Ahsanullah judiciously followed in the footsteps of his illustrious father. Known to be a philanthropist, administrator, generous zamindar, and a learned litterateur, he was appointed to a number of important councils of the colonial administration. He is also credited with the creation of an engineering college, which later became the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (Buet), the country's flagship engineering university. Taifoor wrote in Glimpses of Old Dhaka: "There is no mosque, mausoleum, or important public institution in Dhaka which does not bear the stamp of his [Ahsanullah's] munificence. The electric installation in Dhaka (opened in 1901) for which he contributed four lacs of rupee, has been of abiding benefit to the people of this city."

During the Mughal period, according to some historians, zamindar Sheikh Enayetullah of Jamalpur district had a rongmahal (or pleasure palace) on the present Ahsan Manzil site. Later, French traders bought the palace from Enayetullah's son Motiullah, converting it into a trading outpost and factory. Khwaja Alimullah, the father of Nawab Abdul Ghani, purchased the palace from French traders in 1830 and upgraded the edifice as his family's official residence.

Because his eldest son was deeply pious and uninterested in business and worldly affairs, Khwaja Alimullah made his second son from his second wife, Khwaja Abdul Ghani, the mutawalli (or manager) of the family estate in 1846. A decade or so later, Abdul Ghani hired Martin and Company, a British construction and engineering firm, to create a master plan for the site, with Ahsan Manzil as its centrepiece. Construction began in 1859 and ended in 1872. The old building bought from the French traders was converted into andarmahal (or ladies quarters). The new building became known as Rongmahal and was later renamed Ahsan Manzil.

Ahsan Manzil and its adjacent andarmahal were greatly damaged during a massive cyclone in 1888 and again during an earthquake in 1897. In both cases, Nawab Ahsanullah restored the building, under the direction of a local engineer named Gobindra Chandra Roy. The present dome was added during the restoration work in the aftermath of the cyclone.

To this day, Ahsan Manzil remains one of the finest examples of Indo-European architecture in Bangladesh. The two-story building rests on a 4-foot-high plinth and is crowned with an octagonal dome that soars to 89 feet from the ground. With two symmetrical wings on either side of the dome, the building spans a width of 183 feet. The floor-to-ceiling height is approximately 17 feet in the first floor and 19 feet in the second floor. The interior space consists of four bays along the east-west axis and five bays along the north-south axis. On the second floor, Darbar Hall and Dance Hall (jolshaghar and nachghar and) flank the rotunda on the east and west, respectively. These rooms feature beautifully crafted wooden, vaulted ceilings. Behind them are two large rooms (or mehmankhana) for entertaining guests. There is a spacious dining room on the first floor, directly below the Darbar Hall. The floors of both the dining hall and Darbar Hall are decorated with white, green, and yellow Chinese tiles. Behind the rotunda is a monumental wooden staircase whose wrought iron railings feature vine-leaf motifs. The walls of the palace are 2.5 feet thick. The arched doorways are inlaid with coloured glass and stone.

As the influence and prestige of the Nawab family declined in the 20th century and the descendants of the Nawabs became too impoverished to look after such a vast property, the government acquired the Ahsan Manzil premises in 1952, under the East Bengal Estate Acquisition Act. However, many poor descendants of the Nawab family, as well as needy local people, continued to occupy and squat in the palace until the 1970s. They inflicted much damage to the building by indiscriminately altering its configuration. The palace compound degenerated into a slum. Government intervention seemed inevitable.

Realising the historic and architectural significance of the building, the government of Bangladesh acquired the property through a Gazette Notification in 1985 and, after much deliberation, decided to convert it into a national museum. Under the supervision of the Directorate of Public Works and Architecture, the historic preservation of Ahsan Manzil and its premises was completed in 1989. And, Ahsan Manzil opened its doors as a museum in 1992. That same year, Architect's Regional Council of Asia (ARCASIA) honoured the restoration project with a Gold Medal.

The award citation read: "From virtually a ruin, the Ahsan Manzil has been restored and reconstructed to its former magnificence….The restoration is also an example of a low-budget building program and demonstrates how much can be achieved in Asia when a community believes in the worth and merit of the preservation of fine architecture for the benefit of their economy, culture, and people. It sets an example worth emulating." Today, Ahsan Manzil is a popular museum and a major tourist attraction in Old Dhaka.

Adnan Morshed, PhD, is an architect, architectural historian, and urbanist. He is currently on leave from his faculty position in Washington, DC, and serving as Chairperson of the Department of Architecture, BRAC University. He is a member of the US-based think tank, Bangladesh Development Initiative. He can be reached at amorshed@bracu.ac.bd. [Another version of this article has appeared in his book DAC/Dhaka in 25 Buildings, Altrim Publishers, Barcelona, 2017].

Comments