A 'new normal'?

In its 48th year, Bangladesh faces a new existential question to ponder. What now passes as "normal"?

2019 ushered in not just a change of calendar but a wholly novel political reality. A "participatory" national election that by most accounts, sans the "official" ones, was anything but fair, transparent or credible. A political challenger mostly absent due in equal parts to unrelenting state repression and its own utter lack of strategy. An electorate wanting to partake in the democratic process but psychologically hesitant and stopping shy of protest against rampant electoral malfeasance overseen by the brute combination of the ruling party, officialdom, law enforcement and partisan media.

A yawning gap has appeared between private conversations and the "official" narrative on what transpired on pre-election night and election day and the whole saga has begun to border on magic realism where "what was wasn't" and "what wasn't was".

There is a "new normal" afoot in Bangladesh defined by the uneasy co-existence of two types of "realities". On the one hand, there is a credibility collapse of the election process and a concomitant moral crisis surrounding the right to rule. Three official electoral statistics of the December 30 election underscore the credibility crisis. Firstly, an 80 percent voter turnout figure against visibly thin voter presence. Secondly, an improbable margin of victories with the ruling party "getting" 91 percent of the vote share in 110 constituencies. And thirdly, an unexplainable "collapse" of the opposition vote bank from about a third of the electorate to less than a tenth.

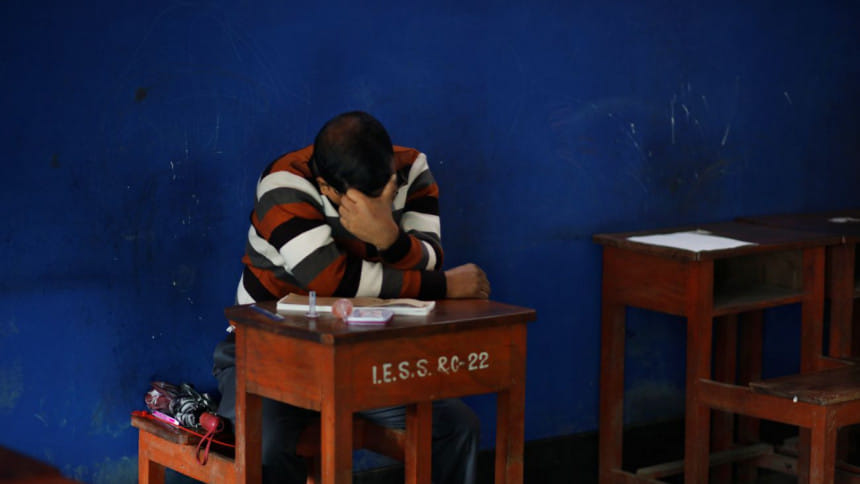

The regime may have been extraordinarily "efficient" in managing the election aftermath but the severity of the credibility crisis surrounding the electoral process and outcome has only gotten deeper as personal and eyewitness accounts proliferate in quiet and unquiet whispers across the land. The belief which has gained ground is that the ruling group is bent on denying an atmosphere of competitive elections. Not surprisingly, voter enthusiasm and voter interest have thus reached a nadir with empty ghost booths becoming the signature image for the just-concluded Dhaka North election.

Yet, it is also the case that people at large have chosen to grieve and despair in private rather than engage in protest and publicly vent their anger at the systematic loss of their sense of being citizens with rights. A country defined by the bravery of its birth is now being defined by an extraordinary sense of powerlessness pervading the citizenry at large. The weakening of political contestation has not merely been a democratic loss but has spawned a "new normal" of political governance built on four pillars: marginalisation of those at the grassroots, political encroachment on social space, economic governance run on crony principles and entrenched corruption, and relentless empowerment of the security establishment over civic rights. The sense of powerlessness is a direct outcome of this "new normal" of political governance. The regime has dramatically raised the cost of protesting with unprecedented partisan misuse of legal procedures as evident in the proliferation of gayebi cases. Justified moral outrage has increasingly come to be balanced against the political calculation of the costs of raising a voice of protest. The outcome more often than not is silence and self-censorship.

Another manifestation of this "new normal" is a paradoxical situation where there is both relative political calm and pronounced uncertainty about the future: a case of "uncertainty despite stability". The stubborn stagnation of the rate of private investment in Bangladesh is testament to an atmosphere of "uncertainty despite stability".

Huntington in his seminal work examined the phenomenon of "political decay" as opposed to political development. A critical insight emerging from such an analysis is that it is less the form of government and more the degree and quality of politics and governance, i.e. legitimacy, opportunities for contestations, rationalisation of authority, state capacity, robust spaces for public discourse, minimising system disruptions around transitions in power that distinguish politically developed societies from politically decaying ones. Sooner or later, political decay impacts economic outcomes, particularly inclusive and sustainable outcomes. Experience shows that there are both well-performing and poorly-performing democracies just as there are well-performing and poorly-performing authoritarian states. The apologist discourse of democracy-versus-development thus entirely misses the point. The discourse nearer to the reality is the tripartite one of democracy, governance and development. A society cannot jettison both democracy and governance and expect inclusive and sustainable development.

Is this the "new normal" Bangladesh is now faced with? Where arbitrariness and lumpen assertions of power are sapping the quality of our institutions across the board? Where all political capital is concentrated in preserving the "new normal" with little left over for the needs for reform that are crying out to be addressed? Where the middle-income dream has been reduced to the narrowest of growth statistics rather than the foundational aspirations of quality, inclusion and dignity?

The "new normal" offers no easy way out for those despairing at the pervasive sense of powerlessness. For the moment, the mood appears to be one of impotent anger, withdrawal and pursuit of private agendas. But it would be a mistake to assume that the will to resist injustices and restore an inclusive dream of quality and dignity has fallen by the wayside. Nothing has come easy in our journey. New answers and new ways forward have to be forged. As before, it will require perseverance and determination. And faith in ourselves.

Dr Hossain Zillur Rahman is executive chairman of Power and Participation Research Centre.

Comments