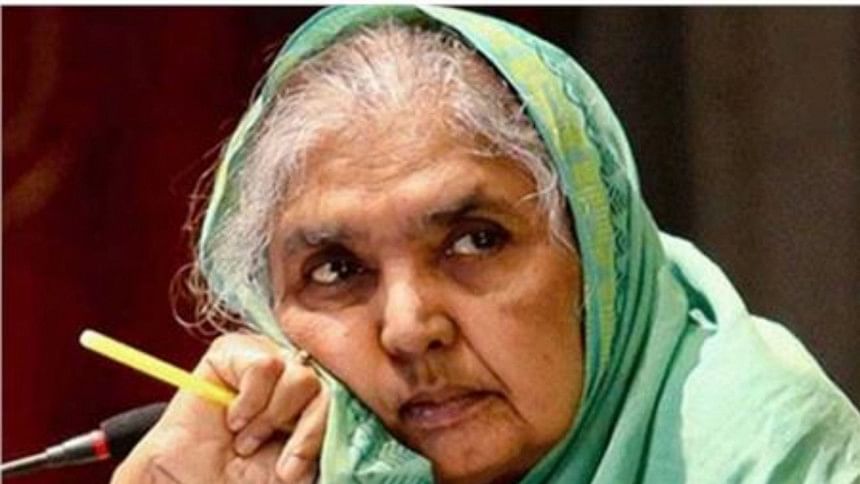

Matia Chowdhury: When personality surpasses politics

Matia Chowdhury left the mortal world on October 16, 2024, ending her long journey as a politician with both significant ups and downs, successes and failures, achievements and faults—which are not uncommon for any important political figure. Some may judge these figures based on their political positions, but to understand Matia Chowdhury, one needs to study her life through a different lens; it is her personal commitment and philosophy of life that determined her politics.

Politicians are usually judged not only by the politics they practise, but also by the life they lead. In the past, politicians used to try to project themselves as goriber bondhu (friend of the poor), while rhetoric became an essential part of their speeches. Many of them kept a set of clothes specially tailored for meetings with the public to appear as the people's leaders. But Matia Chowdhury was different. Though she may have sounded controversial, harsh and unpleasant at times, she never used any rhetoric. Through her lifestyle, she represented who she was: a humble daughter of the soil.

To understand Matia, it is necessary to comprehend her personality which sustained and nourished her political career. Politics was shadhona to her, a lifelong commitment that one has to pursue with devotion. Love for the people and commitment to struggle were two traits she carried deep in her heart, which also explained her plain lifestyle. A biographical note will help us understand how she became a shadhika (devotee) of politics, carrying the best tradition of the Swadeshi politicians in the anti-colonial struggle of Bangalee people. From her student days to the ministerial positions she held, she always wore inexpensive cotton sarees that reflected her unique personality.

Matia went to various schools in Narayanganj, Jamalpur and Dhaka, moving with her police officer father, and was later enrolled at Eden Girls' College. She had wide interests and a broad vision of life. She was fond of reading and acquired good knowledge of literature. She also practised music. Literature nourished her feelings and music her soul. Her literary skill was reflected in her public speeches, which enthralled the student community in the 1960s. But politics did not allow her to indulge in the arts.

Matia's activism to establish the political, economic and cultural rights of the Bangalee people flourished during her student days, when she leaned towards socialist ideals. Soon, she became an important figure in the student movement and was elected as the vice-president of the Eden Girls' College Students' Union. After her graduation, she enrolled at Dhaka University and was elected as the general secretary of DUCSU. As a leading member of the East Pakistan Students' Union (EPSU), she travelled around the country organising and inspiring students as well as the larger community. This was the period when the title Agnikanya (Born of Fire) was bestowed upon her.

She had to pay the price for her baptism of fire. She got arrested in July 1964 in Rangpur and was released after three weeks. Months before her arrest, she married Bazlur Rahman, a promising young journalist and comrade. The newly married couple knew what challenges they had to face in life, and they were ready to embrace that, come what may.

In 1966, the EPSU got divided on nationalist and internationalist positions. Rashed Khan Menon became the president of one faction and Matia Chowdhury of the other. The EPSU under Matia's leadership became a major student organisation. She travelled to many places, giving fiery speeches, and became an icon of the student movement at that time. In June 1967, she was arrested again for making an inflammatory speech in Netrokona. She was produced before the magistrate's court in Dhaka and denied bail. A detention order was issued against her under the Defence of Pakistan Ordinance, which in reality meant indefinite prison term. She was transferred to Mymensingh jail, where there was no separate cell for female prisoners and she had to be confined at the Jenana Fatak, the general ward for female inmates, mostly petty criminals from the marginalised community. After almost two years of imprisonment, she was released in February 1969 along with other political prisoners after the ouster of the Ayub regime by the mass upsurge.

Matia Chowdhury remained almost the same all through her life. She worked at the grassroots level during the early and middle phases of her political activism. From leftist politics, she shifted to the mainstream nationalist party politics, being fully aware of the criticism she would face. The shift in politics didn't mean a shift in her commitment to serve the people, however. This was poignantly reflected in the service she rendered as agriculture minister from 1996 to 2001 and again from 2009 to 2019. Even as a minister, she was no different from the activist on the street. She continued to follow her simple lifestyle, dressing as an ordinary woman. She never sought any acclamation or state recognition; in fact, she consciously avoided the laurels that others chased.

It's worth recalling that she joined the Liberation War from day one and rendered services at refugee camps and hospitals as a trained medical aid. Later on, she toured many places in India addressing meetings and seminars to mobilise public support for the Liberation War. But she never made a claim for any recognition as a freedom fighter or sought any national award.

As an agriculture minister, she will be remembered for many steps taken in support of farmers. Defying the World Bank's dictum, she provided subsidies in the agricultural sector. During her tenure, Bangladesh became self-sufficient in rice production, which was no small feat for a nation that was dependent on food aid and suffered for that.

Matia Chowdhury's account of her prison days was published in 1970, in a book titled Deyal Diye Ghera (Inside the Four Walls). The book also depicts the personality and philosophy of Matia Chowdhury, although she wrote very little about herself and instead highlighted the sorrow and joy of her prison mates, the unfortunate women from rural Bengal. All 29 chapters in the book were about the life of female prisoners and their children (who could stay with their mothers till they reach the age of five or six)—of Rahatan, Champa, Fuljan, Chandi, Nekabanu and many others. Each of the stories was one of passion, pain, suffering, and abandonment told with empathy and love. The narrative showed how deeply she could feel the pain of other people. It was the same spirit which drove Matia Chowdhury, the politician. Occasionally, we saw flashes of her own feelings when she quoted a song, a poem or a line from a novel. After the completion of one year in prison, she quoted from Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace: "Don't grieve dearie/trouble lasts an hour/but life lasts forever."

Matia Chowdhury's lifelong shadhona for the welfare of the people will remain a legacy from which the youth of today can learn and take inspiration, keeping in their heart the intense love for the downtrodden and the work and sacrifices it takes to bring meaningful change.

Mofidul Hoque is an author, researcher and publisher, and a trustee of the Liberation War Museum.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments