Morsi’s end perhaps lay in his beginning

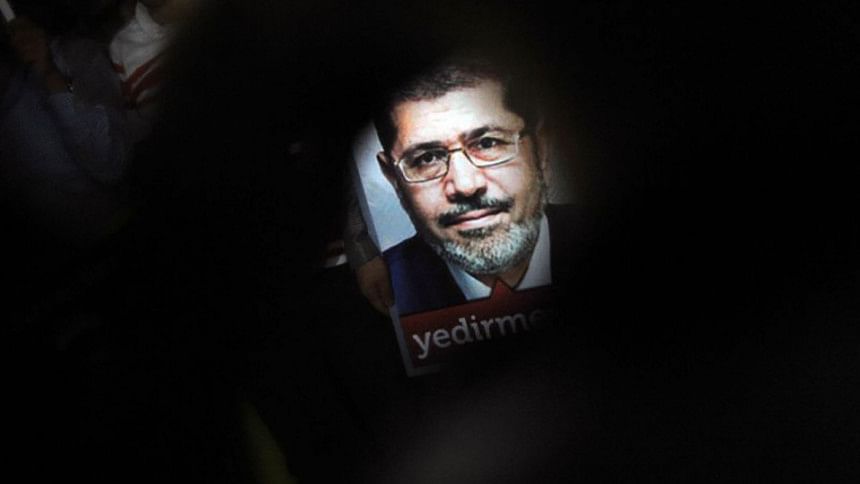

On June 17, 2019, Mohammed Morsi, Egypt's first and only democratically elected president, died inside a glass cage, in an Egyptian courtroom, during the course of an espionage trial. The 67-year-old former president apparently suffered for a full 20 minutes before he was provided with first aid by his captors. The cause of the death was "natural" though—Morsi had died of a heart attack.

Characteristic of the el-Sisi administration, the news of Morsi's death was suppressed systematically, with the government sending a mere 42-word update to news editors across the country via WhatsApp that they were supposed to print and broadcast, revealed accidentally by the embarrassing gaffe of a news presenter.

In the confines of his home, Mubarak is not being denied of medication, the comfort of his home and the love of his family. Why then did Morsi, a man elected by the people, have to die a wretched death inside a glass cage, alone and without comfort?

Morsi was buried in the dead of the night on June 18 in Cairo, apparently in the presence of only two of his sons. And that was the end of Morsi—ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

Morsi's obscure grave, however, is much more than the grave of a fallen man; it is a metaphor for the failed aspirations of the people of Egypt for democracy, for equity.

Mohammed Morsi was much more than just a president; he stood for everything that the Egyptians had hoped for, lit by the signal fires of change in Tahrir Square in 2011. Mohammed Morsi, an academic and an engineer, was an unlikely candidate for the presidency from the very beginning. Morsi was not the party's first choice; it was only after the Muslim Brotherhood's initial choice Khairat el-Shater was disqualified on technical grounds that Morsi was nominated to run for the presidency. In a way, Morsi was an accidental president, and in his beginning as the president lay his end.

In his victory address on television, Morsi promised to unite the country and uphold democracy. The president promised the people that he will work to "restore their rights" and thanked them for their support. Morsi's words were like a breath of fresh air for the jubilant protesters who chanted "down with the military" on the streets of Egypt. Little did they know that in just a little more than a year's time, the military would make a comeback to smother their aspirations for equality and equity.

Morsi, with little governing acumen, had to tread a treacherous path to implement his vision of a free and democratic Egypt. In the process, he made a few mistakes that would ultimately take him to the courtroom where he met his fate.

Morsi's rule, from the very beginning, was challenged by the "deep state", the remnants from the era of Hosni Mubarak who created structural impediments that blocked Morsi's attempts to implement reforms. The deep state, which Morsi failed to dismantle, did not want a democratic government to run the country—that would subvert the edifice of power they had built around themselves. They were threatened by Morsi and the people's mandate for him, and they made sure that Morsi had a troubled journey ahead.

The first impediment came in the form of the eleventh-hour amendments made to the interim constitution by the Egyptian Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) that broadened their jurisdiction and empowered them with more authority, essentially rendering the new president powerless. What followed were multiple attempts by the Egyptian judiciary, still dominated by Mubarak-appointed judges, to thwart Morsi's efforts to implement constitutional changes.

The judiciary had in 2012 disbanded Egypt's first constituent assembly and the first democratically elected parliament. It had also threatened to disband the second constitutional assembly, forcing Morsi's hand to temporarily place himself above judicial oversight, for three weeks, to implement constitutional changes. This was Morsi's first big mistake; at once, it made him look like a new version of Mubarak—a dictator in the making, consolidating more power in his person, a move that made him unpopular among the people.

And the problems for Morsi were not just political. During his year-long tenure, Egypt witnessed severe power crisis and energy shortages, which almost disappeared overnight after the military coup in 2013. Post-Morsi, the respite from these daily troubles was so sudden that even the Egyptians themselves were surprised. Many Morsi supporters later concluded that the energy shortage was an artificial crisis, created by Mubarak supporters and the energy oligarchs, among whom Morsi had little acceptability.

Morsi's biggest failure though was his inability to manage the economic aliments Egypt was facing in the aftermath of Hosni Mubarak's downfall. According to a Guardian report, the country witnessed significant decline in revenues from tourism and foreign investment, along with a "60% drop in foreign exchange reserves, a 3% drop in growth, and a rapid devaluation of the Egyptian pound"since Mubarak's fall, and in the one year that Morsi was in office, he struggled to address these economic challenges.

Morsi's standing among regional powers was also an issue. In a region where most nations are governed by absolute monarchy, Morsi, a common man, elected only by the common people to rule, was seen as an outsider. And he was seen as a threat to the prevailing status quo in the region where memories of the Arab Spring were ripe in the minds of the people. In such a precarious regional context, Morsi's staunch anti-Zionist rhetoric, inspired by the ideologies of the Brotherhood, made him unpopular among international powers, especially Israel and its allies. After the military ousted Morsi and took control of Egypt in 2013, the then US President Barack Obama fell short of calling it a coup.

No doubt, Morsi, in his year in office, had made many mistakes. However, in his address on completing one year in office, Morsi had admitted his mistakes and promised to "introduce radical and quick reforms." Unfortunately, the day he was delivering the speech, army tanks had already been deployed on the streets of Cairo and all logistics set in motion for his fall.

Within days, Morsi was not only out of power but behind bars, and six weeks after Morsi's fall, the Egyptian security forces committed the largest single-day mass murder of civilians in Egyptian history, killing more than 1,000 pro-Morsi protesters at Rabaa Square.

Egypt's dictator of 30 years, Hosni Mubarak, still lives. In the confines of his home, Mubarak is not being denied of medication, the comfort of his home and the love of his family. Why then did Morsi, a man elected by the people, have to die a wretched death inside a glass cage, alone and without comfort?

The United Nations has been quick to call for investigation into the circumstances leading to Morsi's death. But the world at large remained silent, with the exception of a handful of countries which have expressed sympathies for his death, including Turkey and Qatar. The sheer scale of the injustice, however, is difficult for most to digest.

With el-Sisi investing more power in his person through constitutional amendments and referendums, and garnering international support for his controversial regime, only time will tell how long it will take for the winds of change to dismantle the exploitative institutions that are strangling the Egyptian people's aspirations for an inclusive and equitable society. Irrespective of the duration of Sisi's iron-fist rule, posterity will remember Egypt as the nation that was too impatient to give democracy a chance. What started as a wind of change in Tahrir Square ended in the blood of innocents at Rabaa Square.

Tasneem Tayeb works for The Daily Star. Her Twitter handle is @TayebTasneem.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals.

To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments