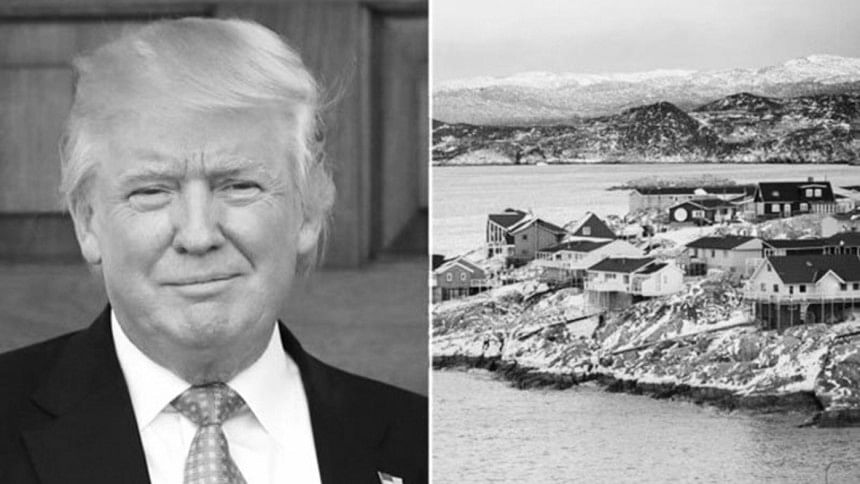

Trump’s wish to buy Greenland

Donald Trump. Boris Johnson. Marine Le Pen. Norbert Hofer. Are they ignorant? Short-sighted? Populist? Call them whatever you want. But the problem doesn't lie with them, it is with the people at large who lack the skills needed to think and decide reasonably.

President Trump wanted Denmark to sell Greenland. He could do such a thing only because he had no idea how much revulsion any Greenlandic could feel at this absurd proposition. Or perhaps he did, but hoped to get away with his antics as he often does. The Greenlandic are fiercely independent, so much so that they left EEC (the predecessor of EU) in 1985 and is moving towards full independence. To them, the slightest notion of Denmark having such an authority on their island would be deeply offending, to say the least.

Trump is not alone. There are many such political leaders in all major democracies who are thriving on the ignorance of the people at large. They have adopted abrasive nationalism, fear of migration and globalisation, intolerance, Islamophobia, religious bigotry, racism, and so on, to strengthen their political base.

Never before, in human history, have so much information been available to so many people, yet we seem to live in an age of stubborn ignorance. We often take a piece of information out of context and arrive at a wrong interpretation due to sheer ignorance of its broader aspects. We do not judge events based on facts, rather we judge facts based on our pre-existing bias. We seem to have totally lost the skills to engage in logical debates, to arrive at an objective view.

In the 1330s, Tuscan scholar Petrarch coined the term "Dark Ages", meaning human knowledge originated in Greece, went to the Romans, then there was a period of intellectual darkness (Dark Ages), followed by the Age of Enlightenment (Renaissance, 1300-1800). Since the advent of postmodernism, scholars started to avoid the term, because it was understood that during the so called "Dark Ages", significant cultural, mathematical and scientific activities were going on in other parts of the world. However, the original idea of the term became popular and remains so to this day.

There have been several versions of American history, each trying to prove a certain narrative. One such was The Light and the Glory: 1492-1793 (God's Plan for America) by a preacher called Peter Marshall (1973). Marshall portrayed the whole story from Columbus's sailing to the settlement of the Pilgrims at Plymouth as God's will. Historians never considered this book as any serious work. Nevertheless, it received a good amount of readership among the "educated" Americans and is still rated highly by the readers (4.6/5 on Amazon and 4/5 on GoodReads).

Interpretation of historical facts to suit a particular narrative has been happening all along. But how can we explain this happening in our time! We don't anymore live in a world where information was available only to a handful of scholars, in high ceilinged grand libraries. Public education is now widespread and information is literally at our fingertips. Yet, we are unable to form reasonable opinions by objective interpretation of facts and evidences.

Meanwhile, our politicians use, abuse, change and change again the past to fit their present interest. George Orwell saw it coming in his dystopian fiction 1984, first published in 1949. It's in this fiction that he made this painfully correct statement: "Who controls the past controls the future, who controls the present controls the past", which has come to be the mantra of today's politicians.

Here is a recent example. When Audrey Truschke from Rutgers University published her 2017 book Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India's Most Controversial King, it stirred a huge controversy in India because it didn't conform with the view the dominant political power wanted to propagate. Truschke had to endure scathing criticisms and countless personal attacks for her work. "You cherrypick instances from the past because your loyalties are to the present", Truschke told a packed auditorium at the Indian Habitat Centre in August 2018.

Dispassionate judgement of historical facts is getting increasingly difficult because we learn less and less from history, and more and more from Google, Facebook, Twitter, films, computer games, TV serials, popular songs, political rhetoric, and so on. Politicians are frequently making ahistorical assertions for short term gains. State machineries are distorting history in a systematic manner, by using every means of mass communication including school textbooks, often portraying the most vulnerable population as enemies, pushing millions to extreme distress.

We live in a world where information is aplenty, but wisdom is not. We prefer information shortcuts, not a whole body of knowledge, to come to a quick conclusion, ignoring that effective use of such shortcuts requires pre-existing knowledge (Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government is Smarter by Ilya Somin). We reject fundamental rules of evidence and refuse to make a logical argument. Our IQ is going up, not knowledge. Learning has become the endpoint, not beginning of education (America's Cult of Ignorance by Tom Nichols).

I will end with a quote from Walter Lippmann (1889-1974), American writer, journalist, political commentator, who stated in 1919, "Men who have lost their grip upon the relevant facts of their environment are the inevitable victims of agitation and propaganda. The quack, the charlatan, the jingo. . .can flourish only where the audience is deprived of independent access to information" ("The Basic Problem of Democracy", The Atlantic). Lippmann might well have rephrased this as "… deprived of the ability to think independently and make a proper judgement based on facts".

We will have more of the quacks, charlatans, and jingoes, unless we raise the quality of well-rounded education, not just IQ or learning. But if our leaders were to understand so much, the problem wouldn't have arisen in the first place.

Sayeed Ahmed is a consulting engineer with experience in infrastructure project management in South Asia.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments