Bern baby Bern: The struggle goes on

On April 8, Bernie Sanders was compelled to fold his bid for the Presidency. Consistent with his decency as a human being, his graciousness as a political opponent, his "real trooper" credentials, his visceral dislike of President Trump (calling him "the most dangerous President in the modern history of the country"), and the dramatically changed circumstances induced by the corona pandemic, he endorsed Joe Biden within five days, in a very pleasant environment. Even though the Sanders campaign ended on an apparently cordial note, the events that preceded the suspension of his campaign tell a sad and sordid tale.

What happened clearly demonstrated that, faced with the spectre of a challenge to the interests of the corporate elite who dominate the Democratic party (as it does the Republican), it would panic, close ranks, and look for desperate solutions. Not since the days of the famous Daley machine, which ran Cook County (Chicago) with absolute authority and discipline in the 1950s and 60s, have we seen the party act with such cohesion. It was even willing to sacrifice the next election in order to stop the "menace" of a message and a movement from its own Left. Through this, the party establishment exposed its political hypocrisies, its moral vacuities and its class anxieties. Some context may perhaps be relevant.

On February 3, Sanders won Iowa, the first caucus state, with 26 percent of the vote, while Biden received 14 percent. On February 11, Sanders won New Hampshire, the first primary state, with 26 percent of the vote, and Biden only eight percent. According to the Marist/NPR/PBS poll of nation-wide Democratic voters, published on February 18, Sanders had the support of 31 percent, Biden 15 percent, and Elizabeth Warren 12 percent, with none of the other contenders in double figures. On February 22, Sanders won Nevada, with 40 percent of the vote, with Biden at 19 percent.

It was too early to talk about a Sanders "surge", but there was momentum, excitement, and optimism about him. That is when he was perceived as a threat which had to be checked. The party moved swiftly.

On February 26, Representative Jim Clyburn, a highly respected African-American leader from South Carolina, endorsed Biden in a moving and resonant speech, emphasising Biden's long and warm association with Obama. Biden, who had been riding on Obama's coat-tails for some time, seized the new opportunity with the gratitude and glee of a two-year old being offered chocolate cake. On February 29, there was a massive get-out-the-vote campaign in South Carolina which Biden carried with 49 percent of the vote, and Sanders less than 20 percent. The fix was in.

Before Super Tuesday on March 3, with contests in 16 states, and 1,344 delegates at stake, Biden received the endorsement of most major Democratic candidates (except Liz Warren). He swept the South, and won 11 states with a delegate total that was almost unassailable. As columnist Van Jones observed, in about 72 hours, the Biden candidacy went from being "a joke to a juggernaut".

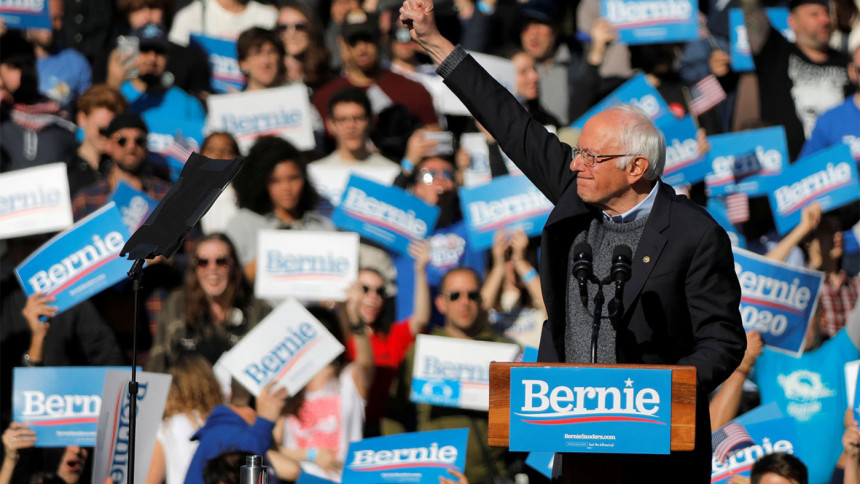

The entire anti-Sanders mantra hinged on one word—electability. This was hardly a tenable argument given the fact that Sanders was defeating Trump in almost all national polls with numbers that equaled or bettered Biden's own, he was garnering more votes than the other Democratic candidates, he was collecting substantially more in campaign contributions (mostly from small donors), and his rallies continued to draw large and enthusiastic crowds.

The reality was obviously at variance with the party "talking points" about his electability. Therefore, given the American obsession with "compartmentalisation" of the electorate, this argument was presented, and must be understood, from the perspective of Sanders' supposed "problem" with this or that group.

The biggest was presumably his "Black" problem. There is no doubt that Biden was much more popular in the African-American community. This, in spite of the fact that his record on race was spotty at best. He had opposed Court mandated school busing. In the 1970s, he had dismissed the question about slavery reparations by saying, "I will be damned if I feel responsible for what happened 300 years back". During the Democratic debate on February 17, responding to a question about the legacy of slavery, his meandering answer appeared to suggest that the problems in the Black community were caused by "bad parenting". Even his endorsement of Barack Obama in 2007, was in language that was patronising if not demeaning, referring to him as "the first mainstream African-American who was articulate, bright and clean" (emphasis added).

In contrast, Sanders was an early and eager supporter of racial justice. In the 1960s, at the University of Chicago, he was one of the organisers of the Congress for Racial Equality. He had marched with Dr King. In 1988, he had endorsed Jesse Jackson for the Presidency (not Joe Biden, also a candidate that year). He had supported the idea of reparations. Moreover, the majority of the Black population below the age of 35 support him. And specific proposals (e.g. Medicare for All) are embraced by Black voters by huge majorities.

It should also be pointed out that his alleged "Black problem" was not a "minority problem". His support among Hispanic voters was broad and deep (clearly demonstrated in Nevada, Colorado and California), his campaign co-Chair is Representative Ro Khanna (of Indian origin), and both the Muslim women in Congress (Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib) have endorsed him.

This raises the issue of his supposed "woman problem". Again, it is true that a slight majority of White suburban women prefer Biden over Sanders. But it is equally clear that among young women below the age of 35, and on specific proposals, his support is overwhelming. Also, it is Sanders who has a squeaky clean image, while Biden has been accused by at least seven women of inappropriate touching, and at least two have referred to his creepy habit of trying to smell their hair (Biden "explained" that he is, after all, a "tactile politician").

Sanders' most complex "problem" with groups involves Jews. This has less to do with the discomfort his Jewishness would provoke in some, given the long and problematic tradition of anti-Semitism in America, and more to do with his acceptance among Jews themselves. This was because of his bold, principled and persistent disapproval of Israel's policies towards Palestinians (particularly pursued by right-wing governments, like the current one), and his position that a mindless and uncritical support for Israel is inconsistent with America's own values, and unhelpful to the cause of a just and durable peace in the region.

There is no denying the fact that the conservative American Israeli Political Action Committee (AIPAC), fiercely dedicated to advancing Israel's interests, is one of the most powerful lobbying groups in the US. Sanders had refused to speak at its events. Thus, he may have an AIPAC problem. As a Reform Jew (the largest Jewish group in the US), he may also have a problem with the Haredim—the ultra- orthodox Jewish groups. But AIPAC does not define the US Jewish community, and the ultra-orthodox are less than 10 percent of US Jews. To reduce the richly textured politics of the US Jewish population to simply these two unrepresentative groups would be misleading. Among other things, it would entail ignoring the inspiring and robust history of Jewish engagement with progressive causes in the US, especially on matters relating to racial equality and social justice, the tradition that Sanders himself embodies.

None of this means that Sanders was not struggling with other "issues". For example, he was considered an "outsider" by the Democratic party because he had always registered as an Independent, and only caucused with the Party in the Senate. His biggest support demographic (the 18-30 year olds) have a notorious tendency to go to rallies, but not vote. Instead of charming "fellow traveler" Liz Warren, he alienated her, and his public spat with her about whether he had said in 2018 that a woman cannot be the President of the US, was unnecessary and unfortunate.

Similarly, his legislative accomplishments were relatively slight. He suffered a heart attack last year. His campaign had initially fumbled with the Black Lives Matter movement. And he could never quite clarify, particularly to an electorate unfamiliar with this language and analysis, why "identity politics" should not be used to under-cut "class politics".

The purpose of this article is not to defend or glorify Sanders, but merely to demonstrate that the "electability" argument was a cleverly manufactured ploy to justify and sell Biden. It is clear that Biden carries enormous baggage as a candidate, being a quintessential Washington insider, a professional politician elected to the Senate in 1972 when he was only 30 (the youngest age permitted) and epitomising the "swamp dweller" that Trump loves to mock. He bears the burden of several scandals (including Ukraine), bad votes (favouring all wars) and rhetorical gaffes (which may suggest some cognitive decline), that leaves him most vulnerable, particularly to an obnoxious person and unethical campaigner like Trump.

Biden is obviously not a better candidate than Sanders, but he is certainly "safer" because he would dutifully safeguard the status quo that benefits the economic elite. Some of Sanders' policy proposals (abolishing capital punishment, elimination of private prisons, a New Green Deal, legalising marijuana, getting rid of the Electoral College, and so on) ruffle some feathers, but are not considered dangerous to their interests.

However, some proposals, and the ones that resonated most with the public, were considered to challenge their economic well-being. Thus, Medicare for all, free college tuition, a minimum wage of USD 15, paid leave for workers, elimination of offshore tax breaks, and most importantly, imposing a wealth tax on 0.1 percent of the population with a 1 percent tax on people with a net worth of USD 32 million, gradually increasing to 8 percent for those over USD 10 billion, were anathema to this group.

Hence, Sanders was perceived to be a threat. He had to be sacrificed. The only alternative available was Biden, however weak and flawed he was as a candidate. This was one of the most shameful manifestations of political cynicism in the service of corporate protection. Instead of a real and meaningful choice between Sanders and Trump in November, the electorate will have to choose between Tweedledee and Tweedledum, essentially two sides of the same coin or, more appropriately, the same dollar.

Undoubtedly, Biden is a far more amiable person, and a hugely welcome alternative to Trump. However, unlike a Sanders victory, a Biden White House would entail major changes in atmospherics and cosmetics, and very minor changes in substance.

The achievements of Sanders were considerable. He demystified the idea of socialism and removed the stigma caused by years of relentless red-baiting propaganda in the US. He breached the "insider-outsider" dichotomy afflicting progressive politics, and was able, as Astra Taylor has pointed out, to graft the energy and radicalism of the streets onto the political process. He brought back the notion of civility, moral authority and "principled seriousness" to a political campaign, focusing on ideas, human welfare and individual dignity rather than personalities, dirty tricks, or facile cliché mongering. He demonstrated that it is possible to resist the seductions and entrapments of the moneyed classes by neither seeking, nor accepting, any donations from them, and repudiating glittering fundraisers in favour of "crowd sourced" small donors. In America, "money talks". Sanders chose not to listen.

Most importantly, he encouraged hundreds of thousands, probably millions, of young men and women to become political, awakened them to the fundamental and structural injustices in US society and the world, provoked them to think through the prism of a different narrative, and instilled in them a belief in, and a commitment to, collective action.

As Ted Kennedy indicated in his concession speech in August, 1980, "…the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die". Neither will the legacy of Bernie Sanders. As he said in his own concession speech, "the campaign has come to an end, our movement has not… The struggle continues".

Ahrar Ahmad is Director-General al Gyantapas Abdur Razzaq Foundation, Dhaka. Email: ahrar.ahmad@bhsu.edu

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments