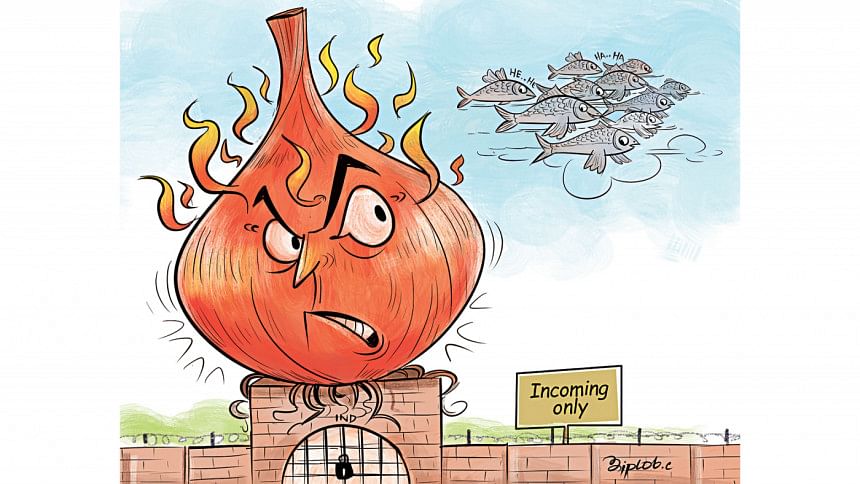

Caught between the humble onion and regal Hilsa

I'm told that there is only one vegetable that can make people cry. And this tubular vegetable is making almost an entire nation cry, except those unscrupulous traders who shut the doors of their godowns as soon as India announced a moratorium on the export of onions. There is no dearth of onions in the country, the government would have us believe, but will someone explain how the price of onions has taken a quantum leap in a matter of 24 hours, if that is the case? If we have enough, then why should it take a month for the price to stabilise, as the commerce minister has said? Is it incapability or unwillingness to take to task the wholesalers, and even some retailers, who are hoarding onions to make hay at the expense of middle-income groups? The ban, we understand, is in disregard of the request that Bangladesh had made to India to not stop export of essential items abruptly and without informing Bangladesh.

This not the first taste of epiphora infused by onion shortages that Bangladeshis in general have suffered. More than a decade ago, there was an acute shortage of onion, that too during the month of Ramadan—the result of a combination of woefully poor planning, machinations and market manipulation by local traders (that being the regular feature of the month of fasting), over-reliance on a single source, and the Indian decision to turn off the tap, abruptly, as has been done this time too. The same thing happened last year also.

The Modi decision is more political than economic, and has little to do with demand and supply. It has more to do with the forthcoming state elections in Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, according to an Indian daily. Hundreds of tonnes of onions, purchased from India and already paid for, are rotting in dozens of trucks on the other side of the Benapole border. There is no earthly reason why they cannot enter Bangladesh unless, of course, the Modi order comes with a retrospective effect. The South Block, we are told, has been taken by surprise by the decision to ban onion exports to Bangladesh, and are even repentant, according to our foreign minister. But one wonders if the embarrassment would stimulate the bureaucrats there enough to counsel the government to rescind its decision. Our government sent a note immediately to the Indian government expressing "deep concern" and requesting it to reconsider its decision. What is of note is not so much the request to review the ban but the apprehension expressed in the text of the letter that the Indian decision is likely to weaken the basis of the mutual understanding agreed to in 2019 and 2020.

Now now! Can a vegetable come in the way of a relationship that has reached a level that (at the risk of sounding Trump-like) no one has ever seen before, particularly at a time when Bangladesh has made a very magnanimous decision to export Hilsa to India (or is it a gift?), temporarily lifting the ban on Hilsa export that has been in place since 2012, keeping Durga Puja in mind? The news was headlined in the Times of India like so—"Durga Puja Gift from Hasina: 500 Tonnes of Hilsa." This is in "tonnes" and not "tons", mind you! That too at a time when there is high demand for the fish in Bangladesh as well. The ban in 2012 came at a time when export of Hilsa to India was fetching us three billon US dollars annually, but the loss of three billion in export earnings was endured to save the fish from annihilation due to over-fishing. In fact, the onion ban came only a day after Bangladesh announced the Hilsa export! Irony?

But this is not the only instance of magnanimity that Bangladesh has shown to India. Apart from the steps Bangladesh has taken to allay many of India's security concerns immediately after the Awami League took over the reins of the government in 2009, many of India's strategic concerns have been addressed to India's full satisfaction. Starting from the transit facility through Bangladesh, a longtime Indian objective, to the expansion of the riverine routes and lastly, direct movement of Indian goods from Kolkata port through Chattogram to the Indian north east. We have even risked one of the most important endowments of nature to Bangladesh, the Sundarbans, to set up a coal fired power plant there, to be built jointly by the two countries.

We were promised reciprocal benefits if Bangladesh were to provide transit to India, which would offset the humongous trade deficit we have with the country. But benefits on the same level are yet to be seen, especially as far as the trade balance is concerned.

There is no doubt that the Bangladesh-India friendship is at its peak now, and the horizon of our friendship is extending evermore. But we should not forget that what we have conceded to be used by India are our strategic assets, and the return accruing to Bangladesh should be in equal measure of that which accrues to India. Surely our facilities are not for free, but is everything that we are getting in return adequate recompense for what we are giving? India is not a landlocked country, and Bangladesh is under no obligation to grant all that it has to India in terms of transit, although the current multimodal transport network has come under the rubric of regional connectivity under the ambit of the Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal Initiative (BBIN).

As behooves a good and considerate neighbour, Bangladesh has perhaps done its bit; many would say even more. Reportedly, we have been very generous in the use of infrastructure facilities and under the new protocol that allows the use of Chattogram port, Indian vessels would get priority for berthing over others. There ought to be a reappraisal of what Bangladesh has gained in monetary and strategic terms exactly, and how much that has ensured the strengthening of our national interests.

With the new transport facilities under the rubric of surface transport, Indian goods are entering the Indian north east quicker than in the past since the distance has been reduced by almost 1,600 kilometres. But the underlying issue is that Bangladeshi products, which had a good market in the north east heretofore, will lose out to Indian products. Have our planners taken into reckoning the consequential loss of market and its effect on our foreign exchange earnings while determining the charges levied on Indian freight carriers for using our territory, either by road, rail and water? Shouldn't a part of the money saved in reduced travel distance come to Bangladesh too?

Also, it seems that we took no lessons from the onion saga last year. Over-reliance on a single source should be avoided, and this applies to not only India but to other countries also. The Indian decision gives us an opportunity to become self reliant in onions as we have become in the case of cattle. It may not always be prudent to go by the theory of comparative cost. One should also consider the theory of comparative advantage even when importing essential goods. What is cheaper may turn out to be costlier in the long run, and the loss is not only in terms of money and opportunity costs. The sufferings that people endure cannot be monetised.

Brig Gen Shahedul Anam Khan, ndc, psc (Retd), is a former Associate Editor of The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments