Commentary by Mahfuz Anam: Stealing From The Poor

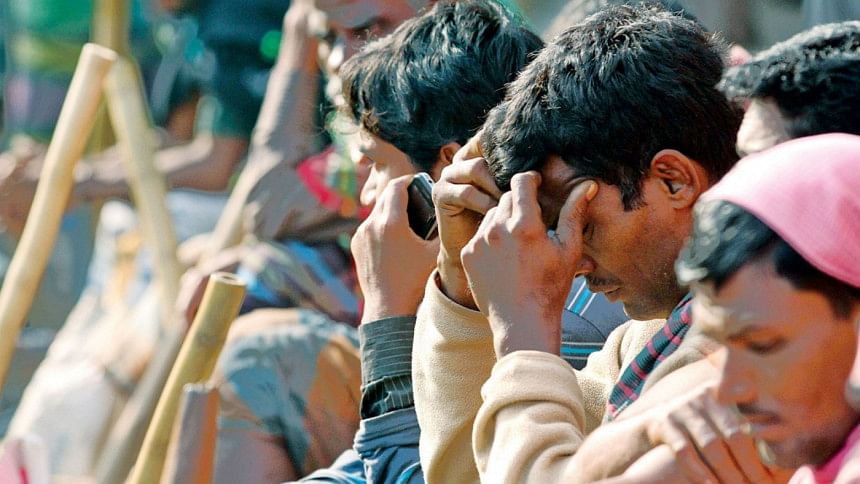

Stealing is bad, but stealing from the poor is perhaps one of the most depraved acts one can think of. But not so for those handling the government's pandemic-related urgent cash assistance programme for the poor. For them, handling the government's dole for those hardest hit by the economic fallout of the pandemic has been the best thing that could have ever happened to them. It is the latest money-making scheme. The government pours in taxpayers' money from one end and the handlers syphon off a large portion from the other and then give out the rest, but mainly to those giving them a cut. This was revealed by the latest Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) study released on November 10.

The government had allocated a total of Tk 111,141 crore for 20 stimulus packages to assist people and absorb the economic shock of the pandemic. Of this grand total, only 26 percent has so far been disbursed. Predictably, the part meant for large and export-oriented industries has been disbursed at an average rate of 73-100 percent, meaning the rich and the powerful got their money right on time, and in most cases, in full. Inflated figures of loss are ruled out as the assessment mechanism was either weak or non-existent. But as we come down lower in the power echelon—the low-income farmers, small traders, small and medium enterprises—the disbursement is between 21 and 42 percent.

The absurdity of the situation, however, is laid bare when we focus on those brought down to the bottom of the economic pyramid by the pandemic. The government had set aside Tk 1,250 crore to give Tk 2,500 each to 50 lakh hardest-hit victims. According to TIB's latest survey report, 69 percent of the surveyed listed poor are yet to receive a single taka even after six months had elapsed. For those who received money, 56 percent were victims of irregularities and corruption. On an average, Tk 220 had to be paid as bribe to get into the list and get their Tk 2,500, from which amount the agent bankers extracted their commission. According to related reports, there were 3,000 government employees incorrectly included in this list, as were 7,000 pensioners. There were 3,00,000 cases of double entry, meaning people who were paid more than once. So widespread were the irregularities that the government stopped this payment scheme after servicing 35 lakh people out of a total of 50 lakh, leaving the remaining 15 lakh with nothing.

So far, 108 local government representatives have been temporarily suspended for corruption—of them, at least 30 have returned to their posts through writ petitions. No other actions have been taken against them.

This, then, is the picture of how the poor have been served in this crisis.

Since the pandemic broke out in Bangladesh in March, the government set up a total of 43 committees to tackle the crisis. Most of them did not function, and some did not even meet, with members crisscrossing committees and named either without consent or never being informed that they were made members in the first place. The only committee that functioned was the Technical Advisory Committee, but its advice was seldom taken or it was not consulted before taking any policy decision or launching any specific action. The committees were a farce, and so were many of the government's actions like providing PPEs or quality masks to the frontline health workers.

An important discriminatory aspect of the pandemic response action plan of the government is the differences in capacities for handling the situation that exist between cities and rural areas. The capital, unsurprisingly, is best-equipped with other bigger cities being somewhat served. At present, 35 districts, out of 64, have no laboratory facilities for Covid-19 testing.

So, with what preparation are we readying ourselves to face the second wave of the virus that is expected to hit us during the winter? We can already gauge the severity of the situation by what's happening in Europe.

Perhaps it is a sign of the wind of "free discussion" that now blows in Bangladesh; so far there has not been any in-depth discussion at any official level about the pandemic. Some brave doctors, specialists and former WHO experts and a section of the media have carried on a valiant—but mostly ignored—struggle to generate some analysis and understanding of what is going on and how we can tackle the situation better. From the side of the authorities, except for occasional press statements and less frequent press briefings, there is very little official initiative to share facts and findings to allow us to better understand the situation and thereby plan our future strategy.

What is incomprehensible is the role of the elected representatives, especially of the parliamentary standing committee on the health ministry. More than 6,000 citizens have died, over four lakh were infected, the country had to be locked down, government offices had to be closed, schools had to be shut for months risking the loss of a whole academic year, factories had to be shuttered, the economy faced a severe jolt—and yet, our parliament did not feel the need to devote even a single session or even a sitting on it. Stranger still is the fact that, according to the website of the parliament, the standing committee on the health ministry—whose job it is to oversee the functioning of the whole health sector—did not think it fit to meet even once in the last seven months even though more than a hundred doctors and nurses have died while serving the infected. The single fact that the government allocated a special fund of Tk 529 crore in the last fiscal year and an additional Tk 9,736 crore in the present one should have prompted this parliamentary watchdog body to see how this huge amount of taxpayers' money has been or is being spent.

Take yesterday's press report on the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) instructing civil surgeons to shut all hospitals, medical colleges and clinics that do not have license. Prompted by the killing of Anisul Karim, a senior assistant superintendent of police, at an unauthorised mental clinic called "Mind and Hospital" (they claim to have a permission from the Narcotics Department which is in no way authorised to issue any license), the DGHS has gone into the present action of closure.

Earlier, DGHS had announced that by August 23, all hospitals, medical colleges and clinics would have to apply for licenses or renew them if they already have one. Thirteen thousand applied online and 2,800 missed the deadline, meaning they did not even bother to apply. Farid Hossain Miah, director of the hospital and clinic unit at DGHS, has given us the comforting news that "there are probably other establishments which are not on this list. We will have to work on this"—for which he wanted "some time", as his office lacked requisite human resources. It boggles our mind to think that there is no complete list of all the hospitals and clinics operating in the country and as such there is no idea of how many are licensed and how many are not—not to mention, how many really heal their patients and how many are there only to fleece them. We are also unaware what are the different categories of hospitals and clinics that are there. For example, how many are of a general nature, how many specialised for specific conditions, such as for mental health, liver disease, etc.

If not in the area of press and opposition politics, complete freedom appears to exist in Bangladesh to set up clinics or hospitals without any prior permission from anybody. If regulations exist, then how can there be so many unauthorised medical facilities wreaking havoc on our lives? Of the 13,000 that have applied online, we don't know how many are for renewal and how many for new licenses. It is obvious from the government notification that many clinics and hospitals are seeking licenses after they have gone into operation. How can that be? How can we allow hospitals and clinics that have not received permission to treat patients in the first place? If these people have done so illegally, in spite of a plethora of laws, then why have we not taken legal steps to stop them and put the violators behind bars?

Nobody can market any product without a BSTI certificate. The control is more stringent for health and food products. But it seems we can open hospitals and clinics—on whose professionalism and quality service our lives depend—and start their operation without any control.

Both the distribution of government financial assistance for the hardest-hit pandemic victims and the handling of the healthcare facilities in general amply reveal the tremendous challenges that lie ahead. Will we take a break from our self-congratulatory rhetoric and undertake some reality checks and act with responsibility?

Mahfuz Anam is Editor and Publisher, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments