Column by Mahfuz Anam: Snapshots from the past, thoughts for the future

Thirty years ago, the coming together of a regionally famous editor and a near-novice at journalism along with some visionary investors—Azimur Rahman, AS Mahmud, Latifur Rahman, A. Rouf Chowdhury, Shamsur Rahman—gave birth to what we called in our first editorial the "Independent Voice".

Readers in Bangladesh were waiting for a non-partisan, fair, decent (with no screaming headlines), well-designed, morally upright and fiercely independent journalistic voice—at that time, it meant only newspapers—and they saw our potential from the early issues. Within months, we were able to make our credible presence felt. And with that, our march forward began, moderately at first, gathering momentum as time passed. Within the first five years, we reached the top spot and, with the unwavering support of our readers, have remained there for the last 25 years.

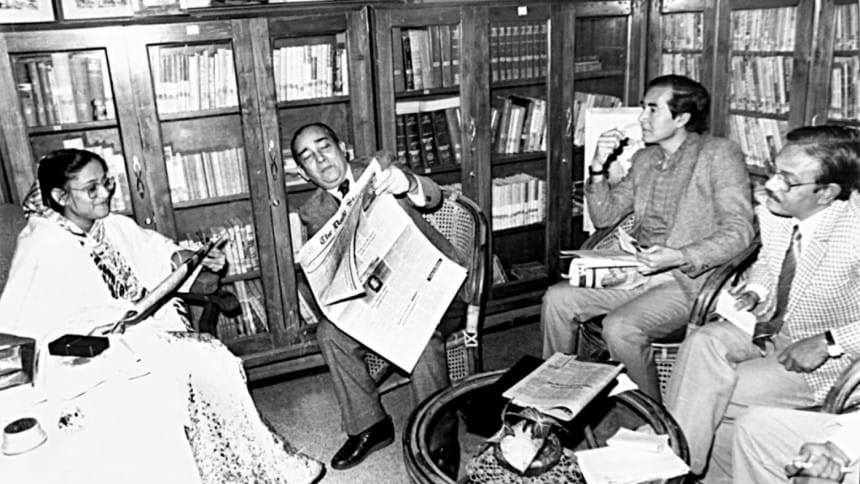

The paper was a while in the making. It started in the 80s, with the frantic exchange of letters between SM Ali, based in Kuala Lumpur, and myself, based in Bangkok, both working for Unesco. The plan was that he would retire, in 1988, and I would resign, in 1990, and both of us would return to Bangladesh and launch our paper. The two-year advance presence of Ali Bhai coupled with my frequent visits from Bangkok, sometimes once every month, gave us the chance to finalise investments (with Mahmud Bhai, our founding managing director, acting as the catalyst), finalise our plans for the paper, wrap up major recruitments, rent the premises, and most importantly, get the "declaration"—the official permission to start a newspaper.

Everything worked like clockwork and the timing turned out to be most propitious—the fall of Gen. Ershad's autocracy and restoration of democracy in Bangladesh. Suddenly, all the fetters were gone. Unity of all political parties gave democracy its due supremacy, freedom of expression found its space, and journalism had the magnificent opportunity to acquire its lustre and glory. And we were there to emerge at that creative moment.

It must be mentioned here that the role of journalism during the anti-Ershad movement was exceptional and most laudable. Our journalists acted in unison to dismantle the repressive regime and played a crucial role in bringing back democracy in Bangladesh. It was a proud moment for our journalism. It was also the last time that all journalists would work unitedly, for soon their representative bodies would go their separate ways on partisan lines.

We got a taste of the emerging intense partisanship in our journalistic community in the early days of the paper. Ali Bhai returned to Bangladesh after more than 30 years, and I after 14. Neither of us had any inkling of the partisan divisions that had already taken root during this time which lay hidden due to the all-party unity against autocracy.

As we invited colleagues to join our paper, it turned out that inadvertently more people in leadership positions were from one side of the political spectrum, creating a deep suspicion in the other—completely unbeknownst to Ali Bhai and me—that we were fronting a partisan venture. Murmuring of this began to trickle into my ears which I conveyed to Ali Bhai, who was as amazed as I was, but couldn't do anything as we were well set on our course. Ali Bhai's overwhelming track record of supporting the liberation movement and my somewhat modest one of being a student activist and a freedom fighter partly neutralised the suspicion, but did not remove it completely.

In 1991, our first observance of August 15, the day Bangabandhu was most brutally assassinated, brought home the external partisanship into our newly-built house. At that time, the general practice was to mention the whole event as an Awami League programme and publish it as a single-column news item, not necessarily in the front page. Very little would be mentioned about Bangabandhu's role in the struggle for our democratic, cultural and language rights, especially his role in gaining our independence. It is hard to imagine the situation at that time.

In contrast to that practice, we published a double-column news item with black borders around Bangabandhu's photo—a well-established practice to show respect—with a staff correspondent's story on his role and the tragedy of his killing along with that of his family.

The external political divide in the journalistic community suddenly turned into an intense internal issue with a strong protest being lodged by a section of our staff, led by a very senior colleague. A big staff meeting ensued in the editor's room where the paper's leadership was accused of being politically biased. Ali Bhai stood firm and rebuked them for their actions. Without going into the details, let me just say that this event led to the resignation of a key figure in the paper, which later led to en masse resignations of 25 staff members including heads of most sections. A major shock for any newly established paper.

Ali Bhai, shocked and hurt, flew to Bangkok for an old eye ailment worsened by the emotional and psychological impact of this event. As his flight took off, I, as acting editor, began to get resignation letters that amounted to 25 within two days. On reaching Bangkok, Ali Bhai's wife, Nancy Wong Ali, asked me not to convey the news of the resignations to him as it could further complicate his situation, since eye ailments are sensitive to the emotional state of a patient.

As this stage, a crucial decision transformed the paper and set it on a trajectory that would make it truly independent. Instead of recruiting replacements from existing newspapers, we took the bold decision to recruit 35 fresh graduates from various universities—except for a few crucial posts. We gave them intensive training through a trainer brought in from London, Daniel Nelson, and inspired them with the ideals of journalism and also gave them the freedom to write as they wished under a strong editorial control at the news, views and editorial levels. It changed everything.

As we played the role of an "Independent Voice" holding "power to account", and being a "watch dog", the party that formed the government in 1991 felt that we must belong to the other side while the party in opposition felt that we were their paper. Thus, we were the "enemy" of the one in power and the favourite of the one in opposition. Then when power reversed in 1996 and we kept on playing the same role, those who once considered us their favourite felt outraged and betrayed (complaining to one of our directors about the editor), while the opposition of the day felt surprised and delighted. As the "Independent Voice", we were at the receiving end of the wrath of both parties, a fate that pursues us till date. The fact that a newspaper can be an "Independent Voice" is not acceptable in our political culture. The idea is, if we criticise one, we must belong to the other.

I recount the above in some detail because both were transformative moments for us, and also because this virus of partisanship—instead of waning as we progressed as a nation—has actually increased, posing, in my view, the most serious threat to the emergence of independent journalism in the country today. The rise of intolerance, which inevitably results from partisanship, is its direct result clouding our mind from distinguishing between what is politically correct and what is objectively so. This is the reality in which The Daily Star has to survive on a daily basis.

Looking ahead, unbelievable transformations in the media landscape are taking place. The digital technology has disrupted journalism like never before, posing a deep challenge for the profession, opening up unfathomable opportunities on the one hand and posing threats to our very existence on the other. While digital technology and the Internet have given us a chance to reach readers and viewers like never before, at the same time, the same technology has transformed the way our readers and viewers receive and consume news, obliging us to rethink journalism as we know it. The netizens, as digital citizens are called, have different priorities, tastes and ambitions than our readers of the past.

The change, not necessarily good always, is here and the need for the profession is to adapt to it as quickly as we can while holding onto our core values.

The transformations of our economy, social interaction, education system, labour market and production process that we have seen during the pandemic should be an eye-opener for us. The e-commerce has turned hundreds of thousands into entrepreneurs, especially women who were fettered by tradition and restricted social mobility. People are contributing to overall productivity in ways that never seemed possible, especially in a country like ours. The media must learn from this experience and change and adopt.

Many feel that the days of quality journalism are over. Our view is the exact opposite. The golden days of quality journalism are ahead. Given the tsunami of news and views through the social media, which are distributed without any or little verification, leading to half-truths or outright falsehoods, readers and viewers are most likely to return to authentic sources of news and views like ours. Here lies our future. This gives us the opportunity of reaching out to a whole new world of readers and viewers through digital platforms that we could never have done with only print. Every media institution—print, TV and online—can now extend multi-media service to its audience. And here lies the great opportunity.

This calls for new journalism, discovering new stories to write about, new ways of writing those stories, new ways of reaching our readers and, most importantly, transforming ourselves from a model of supply-side news business into a demand-sensitive news organisation. All this has to be done without compromising our core values of ethical journalism.

The future lies with quality journalism and that is why we feel so confident about our future. We pledge to serve our readers in every way the digital and other futuristic technology permits us and still maintain the old values of authenticity, credibility and quality journalism that served the cause of freedom everywhere and is essential for the democratic society that we aspire to build here.

Mahfuz Anam is Editor and Publisher, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments