In the shadow of the Super League

Among sport, football perhaps has been used the most as an instrument to placate the masses while consolidating the power of the few.

From Pele winning World Cups to appease a nation under a brutal military regime in the 70s to club ownership being increasingly dominated by oligarchs since the turn of the millennium, the 'people's game' in the 21st century has now morphed into a billionaire's PR project at best and a cashcow for businessmen looking to turn tidy profits at worst.

From a sport that went from being the 'people's game', with community values and entertainment as the focus, modern football finds itself looking to squeeze every ounce of revenue from commercial deals, going so far as to sell the naming rights to legendary venues.

The European Super League (ESL) was a continuation of the hungry capitalism that football has allowed into it, but the reasoning behind the concept was not borne only out of greed, but out of a fair hint of caution.

At the conclusion of the 2018/19 season, the last that was not interrupted by a pandemic, Barcelona earned €166.5 million for winning La Liga while Real Madrid received €155.3 million for finishing second and Atletico Madrid got €119.2 million for being third from the league's broadcasting deal worth €1.42 billion.

Those are big numbers, but even in the 2019/20 season, one that was interrupted due to the pandemic, Leicester City still earned over €155 million for finishing seventh in the Premier League. Champions Liverpool earned just above €200 million that year.

The fear that Perez and Co. have is that they are running out of time to get a bigger slice of the pie in terms of revenue. La Liga's revenue-sharing deal means Real, Atletico and Barcelona always earn the most money in terms of percentage, but the revenue from broadcasting deals is still not close to the levels of the Premier League.

There is a chance to earn more money from the Champions League, upto €110 million just for making it to the quarterfinals, but even that was not enough to allay their worries. The ESL promised billions and from their perspective, European football needed to be saved.

An obscene concentration of wealth at the top of each league is clear to see and the results of that wealth are evident. Juventus in Italy, Paris Saint-Germain in France and Bayern Munich in Germany have all won nearly ten league titles in a row, while Real Madrid and Barcelona lost La Liga just once to Atletico in the past decade.

In England, that wealth is found all down the ladder, especially now. 20 years ago, Manchester City and Tottenham Hotspur would be nowhere near the status they were given as one of the 15 founding member, a privilege that meant they could never be relegated and lose out on revenue from the ESL.

However, despite all their wealth, eight of the 12 clubs that committed to the ESL were bought in the past 20 years and half have amassed debts that the pandemic has made them think are unserviceable. Inter Milan already asked for 200 million in February, while Juventus reportedly must come up with 120 million at season's end. In Spain, Barcelona and Real Madrid find themselves about 1 billion in the red while Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur are both also burdened by debt. The Super League would have given them a way to continue to be callous as revenue would have been guaranteed.

Millions are in fact found all the way down the English table and that enormous advantage which Premier League clubs exert over the rest of Europe perhaps accelerated the jump to the idea that the rest of European football could be left behind.

That also proved to be something of a saving grace, as Premier League clubs banded together to fight against the ESL. Ironically, although UEFA's Champions League has created massive clubs that dwarf most of the competition they ever face domestically. Those leagues, perhaps aware that potential losses in revenue would be irrevocable, gladly deferred the spotlight to their Premier League counterparts.

The ESL probably would not have significantly affected smaller leagues like the Eredivisie anyway, whose players are poached as soon as they show any glimpse of talent. In fact, smaller leagues have been taken advantage of ever since the Champions League decided to go from being a tournament for domestic champions of Europe to on where the champions from some countries and top four or three from other countries would qualify. Without a consistent Champions League place, teams often fail to attract the talents that could change their fortunes.

The last major Champions League reshuffle led to an unprecedented boost in revenue and the formation of a tournament that is known as Europe's elite, but is it not surprising that people suddenly noticed the problem with the ESL only when mid-table clubs of major leagues were asked to deal with issues that already affect everyone else? For many, even finishing as champions of their domestic league is not enough for a guaranteed spot at the Champions League table.

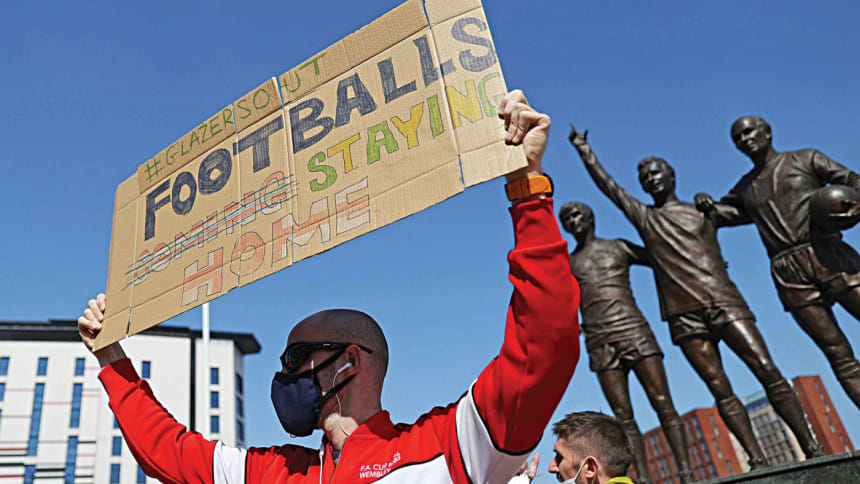

The Premier League and others have been jolted into action by the brazen Super League attempt, knowing that another will always be playing on the minds of the biggest clubs hoping not to fall behind. Boardrooms are in disarray as fans aim to take back their game.

But the job that fans are now tasked with is not simply curbing the capitalistic greed that has pervaded their beloved sport. FIFA and UEFA must also be held to account for inconsistent and toothless policies on racism from FIFA and UEFA, a failure to enforce Financial Fair Play regulations, the debacle around awarding World Cups and the sheer corruption within the sport.

Football's death, like all others, will be a process. The questions on every fan's mind now is: can they stop the process?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments