Has Hefazat been put in its place?

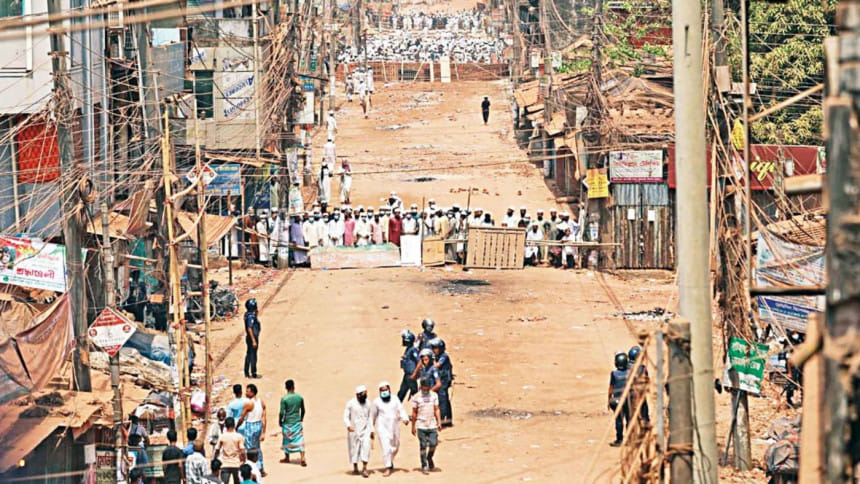

Faced with the full might of the state, the Hefazat-e-Islam has started to crumble. In a sudden move on Sunday night, Hefazat chief Junaid Babunagari dissolved its central committee, as more than half a dozen of its leaders reportedly prepared to defect. On record, they blame what they call a blunder of the Hefazat leadership when the group's angry supporters took to the streets to challenge the visit of the Indian premier Narendra Modi. Off the record, however, they cite serious pressure from the authorities that undertook a multi-pronged approach in dealing with the group.

First, popular Hefazat figures such as the firebrand Mamunul Huq or Nurul Islam had their image blemished with embarrassing leaks about their private life which hampered their political authority, making them a fair target of legal prosecution (some would say, harassment). Second, the arrests of a number of Hefazat leaders, particularly those based in Dhaka, put the group on the back foot. Rattled to the core, its aging leaders were quick to make it clear that the group was no political threat to the government, nor did it have any political ambition.

Third, the carefully orchestrated leaks about the group's senior leaders secretly meeting with the home minister, understandably to negotiate with the government, further hurt Hefazat's uncompromising posture. Finally, the government was able to quickly find support from a few renegades within Hefazat who bolstered the government's position, such as Maolana Abdullah Mohammad Hassan, who resigned in a press conference blaming the Hefazat leadership for the recent deadly violence in Brahmanbaria and elsewhere.

All these factors culminated in a serious crisis for Hefazat, one where Babunagari had little choice other than disbanding the central committee to avoid more embarrassing desertions.

***

The government has treated the Islamist group just like any other political opponent. Incidentally, the recently imposed "strict" lockdown went in favour of the government. With a nationwide lockdown in effect and Covid-19 infections rising fast, Hefazat was unable to summon its supporters to the streets as its leaders were picked up, one after another, by law enforcement agencies.

However, it will be too early to write off Hefazat-e-Islam as a formidable political actor. Its appeal will stay strong to the masses who may view the group as oppressed and marginalised. One would be wise to recall that the group did not need a committee to organise what was possibly the largest political gathering in decades, during its heyday in 2013.

The group's Chattogram-based leaders, except for one or two, have so far avoided any harsh treatment from the government. However, given the still-lingering tensions, it is necessary that both parties take a step back. Hefazat has already signalled its willingness to scale back its rhetoric, and the government may reciprocate.

Although the government refrained from arresting Babunagari and his secretary general, Nurul Islam Jihadi, Hefazat may soon have to compare itself with the BNP's situation during 2008-2013. Back then, the BNP chairperson and secretary general were generally considered safe from arrests, although the party activists had innumerable cases filed against them. But things changed within the span of a few years. If the government crackdown continues, it is a plausible scenario to imagine Babunagari and others in jail in the near future—unless, of course, Hefazat is able to make the tables turn. To avoid a repeat confrontation, both parties should now restrain themselves and live to fight another day.

Surely, the government has many reasons to not let this crisis escalate, one being to avoid a possible political revival of the BNP, which vied with Hefazat for the spotlight in recent years. Once mutually sympathetic to each other, BNP and Hefazat leaders now increasingly consider each other rivals.

Harun Izhar, the charismatic Hefazat cleric, recently harshly criticised a "neo-pro-India" BNP for its "betrayal". BNP secretary general, Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir, complained days ago that their activists were being detained by the government in its anti-Hefazat crackdown. "They often say that [we] are associated with Hefazat. But it is you (Awami League) who are attached with Hefazat. You have struck an agreement with them... the prime minister was awarded 'Qawmi Mother' by them (Hefazat). So are we involved with Hefazat or are you?" he posed the question to the government in a virtual meeting held last week. Therefore, as Hefazat and BNP may see it as a zero-sum game, the government may not yet want to diminish Hefazat and allow BNP to recapture the vacuum.

***

When Ahmad Shafi was at the helm of Hefazat, it reached what seemed like a mutually beneficial understanding with the government, albeit to the dissatisfaction of the country's secular forces. Shafi and others backed down from inflammatory rhetoric against the Awami League. In return, they had some of their demands met by the government, even though some of these demands strikingly collided with the secular ideals preached by the ruling party.

It is strange how realpolitik supersedes ideology. It was only after Hefazat forcefully challenged a core political tenet of the government—its alliance with India's current government—that the group provoked its wrath. Until now, the government was very much willing to entertain this group's regressive, misogynistic and communalist agenda, as long as it did not test the government politically.

Shafi's demise, amid a chaotic internal power struggle within the group, paved the way for Babunagari to become the new custodian of the Qawmi madrasa-based organisation. The government watched warily as the Islamist ideologue started strengthening his support base after taking over Hefazat. In the end, it was probably because of Babunagari's inflexible attitude that cost the group dearly. Its leaders, driven purely by dogmatic rage, seriously lack political shrewdness and maturity to take on a party as resourceful and efficient in political manoeuvring as the ruling Awami League.

Nazmul A Khan is a journalist based in Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments