On Shelley, Shoes and the Shifting of Statues

Where do you stand on this matter of pulling down statues, a hot topic during the ongoing Black and Indigenous Lives Matter campaigns? Do you favour putting up statues at all? Who, if anyone, would you put one up to?

Lawley

In one of R. K. Narayan's delightful stories about the small town of Malgudi immediately following Indian Independence, the Municipal Chairman, having made money from profiteering during the War, decides to make a name for himself by pulling down the statue of tyrannical British imperialist Sir Frederick Lawley.

Pulling down a twenty-foot statue proves difficult and costly. The Chairman finally persuades a local journalist who publicises his doings to take on its removal for its value as scrap metal. Once dynamited and dragged to the journalist's house, only its head and shoulders fit into the front hall. The rest stretches out into the street.

Worse still, when the journalist sends this story up to Madras and it is published, it provokes a national outcry. Sir Fred had been a thoroughly good fellow: cleared jungles, established the first co-op in India, dug canals, argued for self-government and died saving villagers from a flood. Malgudi is shamed. They must put his statue back up.

At first, the out-of-pocket journalist refuses to return the statue. Eventually, he persuades the Chairman to part with some of his ill-gotten gains and win national applause as a benefactor by buying his house and re-erecting the statue there.

Colston & Burke

Arguments about statues of British imperialists in Britain itself came into fresh focus last year when one of 17th century Edward Colston in Bristol was toppled by demonstrators. Although a local benefactor, Colston's profits had been made on the back of the Slave Trade. His statue was briefly replaced by one of a feisty young protester, Jen Reid, who had jumped up onto the plinth after the statue had been pulled down.

Should the imposing old statue be restored, perhaps with an updated inscription on its plaque? Should it be replaced by the livelier, contemporary one of the young protestor? Should there be two statues, confronting each other with their differing outlooks? Or should the plinth be left empty?

Currently Colston's statue, rescued from its watery grave in Bristol harbour, lies on its side in a Museum, captioned with a fuller account of his life. Statues once brought down and no longer so high and mighty can even become rather endearing. Some years ago you could see a statue of Edward VII reclining in wasteland adjoining New Delhi Railway Station. The king looked like just another weary traveller who couldn't afford a third class ticket.

Bristol has another (unnewsworthy) statue: that of Edmund Burke, who (in one of history's intriguing might-have-beens) turned down a job in Bengal the year Hastings became Governor. Time has not yet taken its toll on Burke's conservative principles, although his paternalist attitude to Africans and Slavery is now questionable. Whose in 18th century Britain isn't? Whose in the 21st century isn't? Elsewhere too? Hubshees?

Clive

Surprisingly, Burke was an apologist for Clive of (don't make the palasi trees laugh at such a breeze) India? There's a statue of British India's first Governor of Bengal in London's Whitehall. It was commissioned not in his own lifetime but in 1911. Its erection at a time when the imperial capital was being removed to Delhi in part on account of increased nationalist agitation in Bengal was even then criticised as unduly provocative. Its continued presence is proving just as controversial.

If Clive, who now stands outside the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (with its grand Durbar Hall), is not destined to be relegated to, say, Churchill's war-time bunker beneath his feet, perhaps he should at least be confronted in King Charles Street by a new statue of a famine-wracked Bengali peasant family?

And why only in London? Should we suppose such an idea horrifies the bhadralok of Kolkata? At the moment not only does a statue of the scavenging Clive perch unchallenged in Lord Curzon's triumphalist Victoria Memorial but one of Edward VII also travels in the Viceroy's train. How long will it be before these dusty relics fade into a jadoo ghar of curiosities?

Gandhi

Few, if any, statues can escape becoming one of Time's laughing-stocks. Anti-imperialists felt vindicated when, several years ago, a statue of Winston Churchill (also known to Bengal) was joined outside the Houses of Parliament in London by that of the man he once described (inaccurately) as posing as a fakir, Mohandas Gandhi.

Hardly had this statue gone up – complaints concerning the long suffering of both Churchill's and Gandhi's wives being summarily dismissed – than students in some parts of Africa began pulling down statues of Gandhi. In London, his was even tarred with the same (anti-racist paint) brush as Churchill's. In his own country, of course, it was not his statue but the man himself who had been brought down.

Worker

Culture Wars concerning the erection or demolition of statues of figures caught in the tangled web of history invariably serve contemporary political agendas. After the Fall of Communism in 1989, the City Government in Budapest pulled down some 40 statues erected during the previous socialist regime. They did not tip these into the Danube but consigned them to a park on the outskirts of town.

Among the exhibits are several to ordinary workers. These, if any, might have been left standing? They are surely less objectionable and subject to the changes brought about by Time than those of ideologically committed politicians and other such dignitaries?

Shelley

The absurdity of having statues at all may best be illustrated by that of the poet Shelley at University College, Oxford. Leave aside that, commissioned by the family, not the college, the statue was originally intended for Rome, not Oxford. Leave aside that, until properly protected, it was regularly subject to trashing from foolish students. Leave aside the ultimate absurdity that the college actually expelled Shelley.

More to the point, Shelley, England's most visionary poet – read Prometheus Unbound set in the Indian Caucasus if you don't believe it – would not have wished to be transfixed in anything so material as a statue, beautiful as may be its marble representation of his recumbent dead body. In Bengal, he would have been a baul. Drive my dead thoughts over the universe/ Like wither'd leaves, to quicken a new birth. Shelley is a spirit.

Shoes

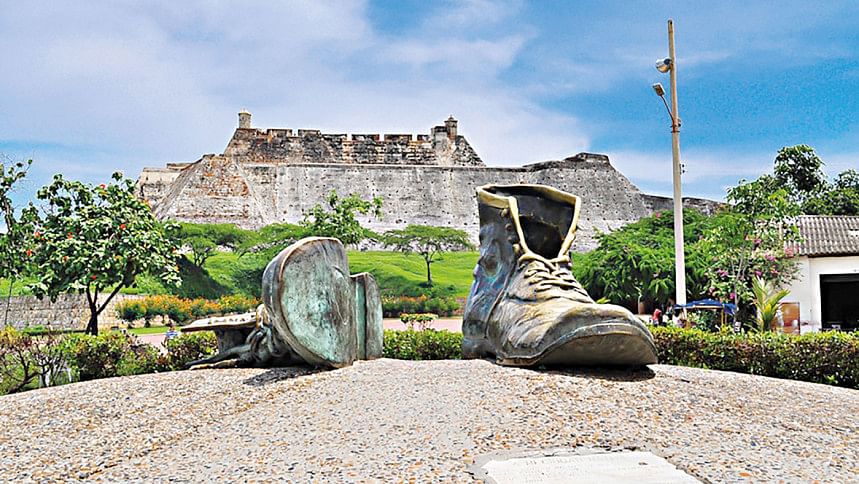

If you want a statue at all, one attractive possibility is featured in a poem by Earle Birney. He records how alien he, a Canadian tourist, feels one day slinking guiltily through the impoverished Latin American town of Cartagena de Indias. Suddenly, to his amazement, he comes upon a statue of a pair of old, battered shoes.

Upon further enquiry, since the plaque under the statue does not (like plaques in Bristol and London) tell enough, he discovers the town once had a poet, Luis Lopez, who was utterly infuriated by the squalor of his native place. The best Lopez could say of it was that it was like a pair of old shoes you loved and couldn't get rid of. After his death the town chose to raise this form of memorial to the poet.

Human beings have feet of clay. Better not to put up statues of them? Just of their shoes? Or, for those who don't have any shoes, their feet of clay?

John Drew once wrote a book of verse-fables about a statue, The Buddha at Kamakura.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments