Empathy and Bangabandhu

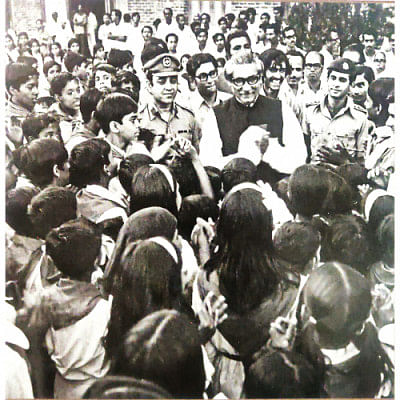

Empathy, the Wikipedia entry on the word tells us, includes "caring for other people and having a desire to help them; experiencing emotions that match another person's emotions; discerning what another person is thinking or feeling; and making less distinct the differences between the self and the other." To anyone who has read Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's published works or heard at least a few of his speeches, it will become obvious that these are the qualities that made him come so extraordinarily close to people throughout the length and breadth of Bangladesh as well as elsewhere, and led him to represent them. That is exactly what made him win the hearts of his people.

Bangabandhu's posthumously published works evidence endlessly his capacity for empathy. Read The Unfinished Memoirs (2012), for abundant examples of his caring, giving nature and ability to empathize with others. Not part of the original manuscript, but placed as the apt epigraph of this most caring and fatherly of all leaders, we read these very apt lines he had scribbled in English in his personal notebook on May 3, 1973. "As a man, what concerns mankind concerns me. As a Bengalee, I am involved in all that concerns Bengalees. This involvement is born of, and nourished by love, which gives meaning to my politics and to my very being."

In The Unfinished Memoirs we thus find the 17-year-old following his tutor's advice to work for the Muslim Welfare Association in Gopalganj "to help poor students" of the town (8), even doing so, as he himself confesses, quite aggressively at times. In Kolkata, and while studying at Islamia College, he tries to alleviate the sufferings of the famine-struck people of the city as well as of his home town, Gopalganj. He becomes heavily involved in "the famine relief effort"; along with others, he "opened quite a few gruel kitchens" then (18). Initially opposed to the Muslim League because he felt that it was largely directed by the moneyed class, he later joined the party because he was attracted to Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, clearly because he found in him the quality basic to all empathetic people: he was such "a generous man!" (51). In the Calcutta riots of 1946, we find him defending Muslims but also rescuing stranded Hindus and deploring people who had "lost their human sides in the violence" (69). Soon, he volunteers to join in relief efforts going on in Patna, once again moved by empathy, which made him reach out to the distressed now as always. At the end of the Calcutta and Bihar riots and subsequent bloody events related to the partition of India, Bangabandhu had learnt a lesson from the hard, horrifying times that he would soon be delivering to everyone and that would be one of keystones of his subsequent political philosophy when he moved to Dhaka in 1947— "the most pressing need of our time—[is] communal harmony" (90).

In Dhaka we see Bangabandhu reaching out—sometimes way out—to help people in distress. In addition to getting involved in the movement to establish Bengali as a state language of Pakistan and in student politics, he joined the movement to support farm laborers in Faridpur, Cumilla, Dhaka and Khulna districts deprived of their rightful share because the government had arbitrarily decided to enforce the "cordon" system" even after these migrant and seasonal laborers had done their work. In between his travels to these and other districts, he joined the movement of the lower-class employees of Dhaka University, not only agitating for their rights but also joining other student activists to raise funds for these unjustly deprived poor people.

Because he felt that the Muslim League leaders had totally alienated themselves from the masses by such arbitrary measures and its support of leaders who had no feelings for the Bangla language, Bangabandhu decided to abandon the party and help form the Awami Muslim League. He realized that the Muslim League simply was not interested in doing anything "to alleviate their sufferings" (134). How could he, truly a man of the people, be with the Muslim Leaguers? Empathy, here and everywhere, motivated Bangabandhu to good works and directed his political moves. For the suffering, he was always willing to give up everything. As he puts it at this point of his narrative: "I was able to come to the conclusion that to engage in politics one must be ready to make huge sacrifices to make our people happy" (137). To be a truly successful leader, what was needed he knew by instinct as well as by his own observation of the failure of the Muslim League and the popularity of pro-Bangladeshi leaders like him springing up everywhere was that "people can be won over by good manners, love and sympathy and not by force, hatred or oppressive means" (201).

An interesting passage in The Unfinished Memoirs reveals the eco-critical consciousness that Bangabandhu feels had been nurtured in him by Bengal's landscape—as opposed to the harshness of the desert landscapes of West Pakistan. Such consciousness leads to love of nature as well as nurtures in people empathy for the land and its people. In his first visit to Karachi in 1952 we find him thinking about how wherever one gazed in Bangladesh "one saw a sea of grass." How could one born in such a land ever get to like "the pitiless landscape" he saw spread before him now? For him the conclusion was inevitable—pity and sympathy for others are bred in his people from birth— "we were born into a world that abounded in beauty: we loved whatever was beautiful" (214).

Bangabandhu was clearly an unabashedly sentimental as well as patriotic person. An instance of how he could be both emotional and compassionate can be found at the end of the book when he narrates an encounter he has with an impoverished old woman while on the campaign trial in his constituency during the 1954 provincial elections. The woman had been waiting for hours because she had heard he would be in the area. She offered him milk to drink, betel leaves to chew, and even a little money to help him out in the elections. Listening to her, Bangabandhu says in his autobiography, he would leave with "eyes… moist with tears." On that day he promised himself: 'I would do nothing to betray my people" (261).

The Unfinished Memoirs has become a valuable source for anyone trying to understand the early life and times of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. However, anyone trying to understand fully the man who is the founding father of Bangladesh, including his capacity for empathy, should also read his other posthumously published works. The Prison Diaries (2018) is an essential sourcebook for those wanting to know more about his consciousness and the reasons behind his greatness. Written during and about various prison terms that he served because of the West Pakistani politicians and generals and their East Pakistani lackeys who wanted to disable him politically, this book contains a wealth of information illuminating his personality and illustrating the benevolent and humane emotions that drove him.

The first of the four notebooks reproduced in The Prison Diaries contains detailed descriptions of prison and prison life. Anyone reading it will be enlightened as well as entertained with details that show how observant, insightful, thoughtful and at times humorous Bangabandhu was in assessing people inside prisons, and in critiquing the disciplinary and power apparatuses that controlled them. But one notices too his empathy for prisoners, especially the mad men confined there. Clearly, society found it easy to resort to incarceration of people it should have attempted to cure and not punish. Note thus his dismay with the guards who tortured prisoners physically and mentally or abused them. In his prison encounters with them, he chose rather to resort to other, humane methods to calm them down. Talking to them and counselling them were measures we see him deploying in his dealings with such prisoners here and in the other note books. Bangabandhu's compassionate accounts amply indicate that a man is not born to be a prisoner; unjust and unsympathetic systems mostly make prisoners.

The remaining three books of The Prison Diaries focus on the time Bangabandhu spent in prison in the later 1960s as East Pakistanis moved closer and closer towards becoming Bangladeshis inspired by his visionary leadership and sacrifices. But everywhere in these notebooks readers continue to meet the caring, altruistic, compassionate man reaching out spontaneously to help others in trouble. In the entry for 9 June, 1966, we thus read of his concern for young men herded into cells after being beaten up badly by the police. What he does next is to persuade the guards who clearly respected him a lot to ensure that these young prisoners were not abused physically anymore and given water to bathe and food to eat.

In prison, Bangabandhu's main link with the external world is the newspapers delivered to him. As he reads them, he keeps thinking about the plight of his people. A report about the havoc floods were causing that year to Bengalees depresses him but also makes him indignant about a careless government. Why was it letting its citizens starve and do nothing about the floods? Why had the government stopped importing bidi leaves—driving bidi workers into unemployment? When his wife brings food she has cooked for Bangabandhu in one of her visits, he shares them with the other inmates. The entry for 28-30 April, 1967, in fact, shows him taking advantage of extra food items supplied from his house as well using his jail quota to cook a Khichuri dish to the prisoners and guards around him!

An absorbing aspect of The Prison Diaries is the empathy Bangabandhu shows for the prison's avian visitors. When two yellow birds he would see regularly in a past prison stint don't show up in the term he was serving then, in his notebook entry of 18 June 1966, he tries to imagine the birds' feelings about him. He wonders: had they left because "they had become upset" at his not being there for them in those years (95)? A little later we see his happiness at a hen and its chicks and a pigeon that has befriended him. He tells us with the ecological consciousness referred to above, "Trees, the yellow birds, the swallows and the crows are my friends in the lonely corner" of the prison he is allowed to go out to in the daytime (230). He protects the pigeons fiercely from the guards and others who might bother them. His only enemies are the crows who bother him, but even they, he feels, can teach Bengalis a lot when he sees three of them unite to defeat an aggressive jackdaw. There is a lesson for them here: "If Bengalis could unite and stand up against the jackdaw as one, they would surely emerge victorious" against their Pakistani foes! (231)

The last of the three posthumously published works based on the prison notebooks Bangabandhu left behind, New China 1952, a detailed account of his trip to the country to participate in the peace conference of the Asian and Pacific Region as a member of the Pakistan delegation, shows abundantly Bangabandhu's capacity for empathy, his caring nature and his attempts to reach out to people in all sorts of ways. For instance, we have Bangabandhu's thought about Mao Zedong after attending a dinner reception in which Mao had presided. Why did the 600 million people of China love him so much? "He had sacrificed so much for them; his people love him and trust him because he is someone who loves his country and his people" (69). In a visit with others to where worker have their residences, he spontaneously offers his ring to the woman who receives them in one such quarter, since he cannot think of visiting someone who is newly married without giving a gift.

Everywhere in his China visit, Bangabandhu kept thinking about how his own country could be transformed by learning from the successes of the Chinese revolutionary government. When he sees Chinese children with smiling faces and healthy bodies, he thinks instantly "about the unfortunate children" of his country (78). Thinking of the women Bangabandhu comes across in the transformed China, he thinks ruefully "My homeland was a place where our womenfolk had to starve to death" (82). In Nanjing, he plays with children members of his delegation come across, even delaying his group's visit for this reason. But he has the kind of personality that cannot help but reach out to others—old or young. As Bangabandhu says in the entry, "I love mingling with children" (88).

Reflecting on the success the Chinese had in rehabilitating women who had turned to prostitution because of poverty through well-planned schemes, Bangabandhu thinks of women he had come across in his country and their fathers who had no access to such schemes. We learn at this point how he had even "skipped" his "intermediate examination" so that he could "devote" himself to relief work during the 1943 Bengal famine (127).

Bangabandhu reveals his concern at the plight of women in his own country who cannot be married off because of their parent's inability to pay dowry. This moves Bangabandhu to his resolution to "launch a campaign against this practice" along with others on his return (129). Indeed, quite a few pages of New China 1952 are devoted to Chinese women, for their transformed situation seems to have led to extended reflections in him on how to alleviate the sufferings of Bengali women. Bangabandhu has no doubt that "if half of a nation's people end up doing nothing but giving birth to children, it will never be able to attain any kind of status in the world" (132).

The three posthumously published works based on notebooks that he filled up in the many prison terms Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was force to serve time and again reveal a man who had an extraordinary capacity for empathy, for loving others and caring for all living things—human or non-human. His caring nature is consistent in these notebooks and we see him putting himself in the situation of the distressed or deprived and standing up for the oppressed time and again. We see him too trying to experience the emotions of the suffering—whether women, men or even the animals he came across in prison. A loving son, husband and father, he will leave them and even go to prison repeatedly to help others and stand up for the rights of the subjugated and deprived people of Bangladesh.

On August 15 every year, let us remember how this loving, compassionate and large-hearted man was gunned down mercilessly along with all his family members except his daughters by men who had no human side to them and no compassion at all. Let us learn from Bangabandhu's life and works as we move forward in the task of developing our nation to the utmost and follow him in cultivating our human side for our own self-improvement as well as for building a better Bangladesh.

Fakrul Alam is Director, Bangabandhu Research Institute for Peace and Liberty, and UGC Professor, Department of English, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments