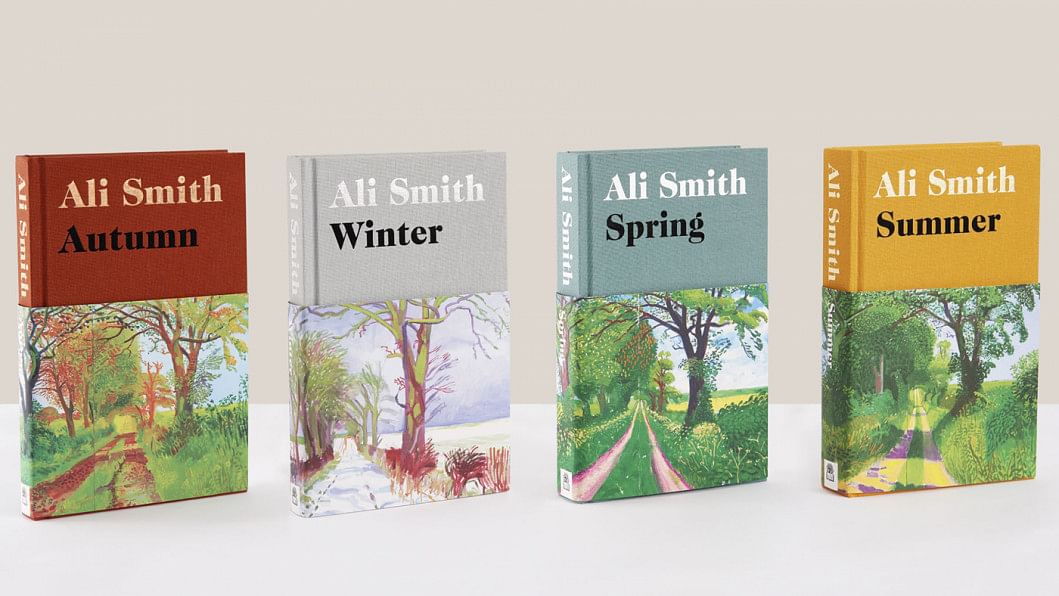

Ali Smith's 'Autumn': Many shades of a golden season

Fifteen pages into Ali Smith's Autumn—the first installment of the Seasonal Quartet, we are introduced to the protagonist (to the extent they exist in her books), Elisabeth. She's standing in a long line to renew her passport. Seeing the slow progress, she goes over to a bookshop next to the post-office, and buys herself a copy of Brave New World—a dystopian novel where humans are manufactured in assembly lines and essentially treated as consumer goods. Elisabeth comes back, only to fall behind in the queue, and this time, forced to purchase new tickets, as the old ones are no longer valid. When she finally reaches the counter, she's made a sizable dent in this otherwise fat book. Her passport renewal form is eventually rejected after a series of back and forth with the officer in charge, as the photos she attached do not meet the requirements.

Much of the novel takes place in these encounters between individuals, who are trying to communicate with each other, but often more unsuccessfully than not. The external world has made it difficult for words to have meanings that they can both comprehend. Elisabeth Demand is a 30-something-year-old art student at a London university. Daniel Gluck, now 100 and in a hospice, is her childhood neighbour, under whose care Elisabeth's mother often left her. He has been a huge influence on her, so much so that she often sits by his bed silently and remembers the conversations she has had with him. Daniel, while unconscious, searches through his fractured memory, trying to recall what life was like when he was young.

Conventional literary devices are rarely present in Smith's novels. We have a residue of a plot, if one can call it that. Her characters do not feel like real people and are never fully fleshed out; they are at best teased, to get at something larger. Here, it is time. Autumn itself is a period of transition. Daylight becomes noticeably shorter; nights increase in length. Leaves announce with their colour that they are prepared to shed. Smith punctuates the book named after this season with lush descriptions of temporality of nature, but starts it with an invocation of Charles Dickens and alters it to her purpose. "It was the worst of times. It was the worst of times."

And indeed it was. Autumn (Hamish Hamilton), written in 2016, takes place under the long shadow of the Brexit referendum. Across the pond, Donald Trump is running for the presidency of the United States. The world is changing, and changing in a way that's hard to understand, and the tools that are supposed to help make sense of this change are futile, if not complicit. At one instance, Elisabeth's mother says,

"I'm tired of the news. I'm tired of the way it makes things spectacular that aren't, and deals so simplistically with what's truly appalling. I'm tired of the vitriol. I'm tired of the anger. I'm tired of the meanness. I'm tired of the selfishness. I'm tired of how we're doing nothing to stop it. I'm tired of how we're encouraging it. I'm tired of the violence there is and I'm tired of the violence that's on its way, that's coming, that hasn't happened yet. I'm tired of liars. I'm tired of sanctified liars. I'm tired of how those liars have let this happen. I'm tired of having to wonder whether they did it out of stupidity or did it on purpose. I'm tired of lying government. I'm tired of people not caring whether they're being lied to any more. I'm tired of being made to feel this fearful. I'm tired of animosity. I'm tired of pusillanimosity."

If Autumn is about anything, it is the banality of daily life, which increasingly seems to be the grand subject of contemporary fiction. But what sets Smith apart from the likes of Karl Ove Knausgaard, Rachel Cusk, and Deborah Levy in their shared chronicling of late stage capitalism is her interest in outside forces. The external world is explored through the characters' interiority. Elisabeth's kafkaesque experience with bureaucracy is a prime example of how major political events change minute details.

But Smith's vision for the world in this novel also includes tenderness as a response to cynicism. Her omnipresent narrator is able to negotiate the difficult with real vulnerability. A fearful Daniel, at one point in the novel, is contemplating the afterlife: "He has made something, something of himself. His mother would be pleased at last. Oh God. Is there still mother after death?"

Certainly a grim topic to think about in a rather grim setting, but in Smith's prose it becomes a wondrous and exuberant moment. It's not Daniel's mother, or the mother. It's just mothers. She invites the reader, at least yours truly, to think about death and what and who remains with them afterwards, from a fresh perspective.

Minhaz Muhammad is a contributor.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments