Abdulrazak Gurnahs 'Afterlives': The repercussions of colonialism, unveiled

Abdulrazak Gurnah, this year's Nobel laureate in literature, seems to come as an admirable choice compared to the Nobel Prize's controversial recent history. The Nobel committee has, at times, stepped over viable candidates who in their words were "too predictable, too popular", or at others have selected candidates who were allegedly genocide deniers or apologists, such as the Norwegian master, Knut Hamsun, and the controversial 2019 laureate from Austria, Peter Handke. The prize has been credited for bringing literary lights out of relative obscurity and propelling them to superstardom, while at the same time overlooking some of history's literary heavyweights, such as Tolstoy and Proust. It has also selected only 16 women out of the 118 winners of the award since 1901, and is often critiqued for featuring white, Western authors too often.

Gurnah, a Zanzibar-born Tanzanian writer living in the United Kingdom, has been chosen for his "uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents." In many ways, Gurnah's own story paves the way for his novels, as the author escaped the Zanzibar Revolution in the 1960s when the ruling Arab classes were being hunted down by Black African revolutionaries.

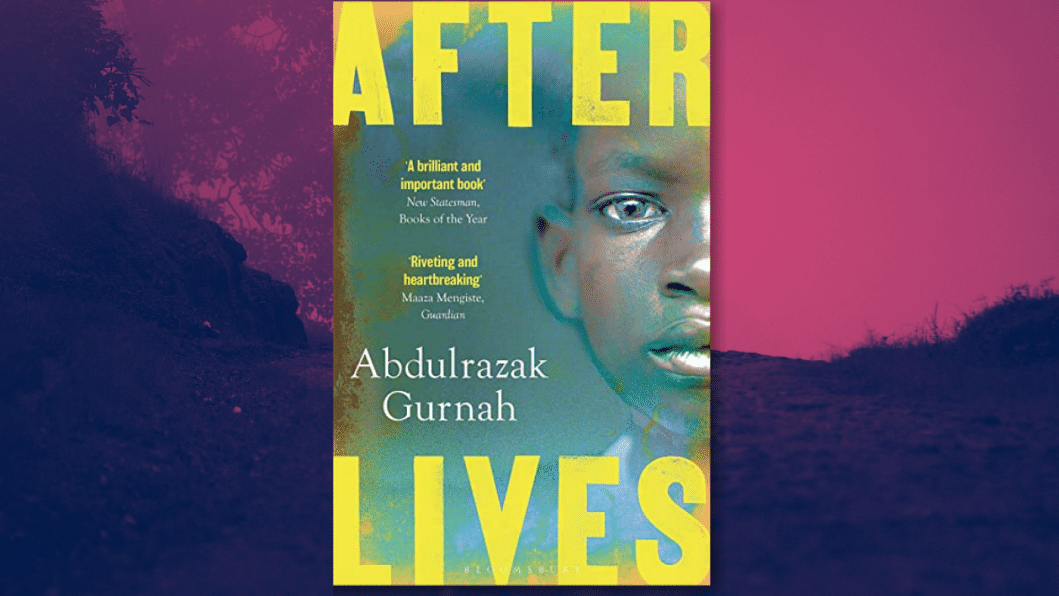

Afterlives (Bloomsbury, 2020), his most recent novel, showcases a darker and humane side of the complex relationship between the realms of the oppressor, the oppressed, and the by-standers. It takes us to the region of Tanzania, East Africa comprising Uganda, and Kenya that is expanding under German colonial forces and wrestling with other colonial powers such Britain, in the early 20th century.

Gurnah presents a host of diverse characters, such as Khalifa, a merchant-clerk of Gujrati-African heritage; Khalifa's wife, Asha; Hamza and Ilyas, voluntary soldiers in the German Colonial Army (Schutztruppe); and Illyas's orphaned sister, Afiya.

Together, they paint a devastating canvas of terror, warfare, bloodshed, and exploitation, which occurs in the name of bringing civilisation to Africa. All of this is personified in the rather ambiguous conduct of one despondent German officer sent to the region to lead the military forces. He treats his African soldier, Hamza, with a conflicting mix of contempt and affection—deriding him for his "savage" backwardness while having hopes of him learning the ways of Europe. It is only after learning German and reading the philosophy of CF Von Schiller that Hamza earns the approval of his superior, but his relationship with the German Colonial Army remains a major site of contestation for which he struggles to reaffirm his sense of worth and identity.

It is Hamza's complexity of character which makes the novel a mediator between the colonial and post-colonial experience, evoking the themes of love, estrangement, uprooting, and reconciliation. And through Hamza's interaction with the Khalifas, and with Afiya, the woman of his dreams, we see the impact of war on African soldiers who were either coerced or compelled into fighting for the colonists.

Written in a third person narrative, Gurnah's prose is just as piercing as his observation is deep and jarring. He humanizes the colonists and the subjects rather than impose constrained binaries. As in his previous books, he brings to life the experiences of Muslims residing near the Indian Ocean amidst its multicultural setting—the sounds, the tastes, and the smells of their daily lives in East Africa come through in vivid amalgamation. And he creates a sense of intimacy using a smattering of Swahili and Arabic phrases to mesh the worlds of natives, migrants, and colonists into a world of fluid literary imagination.

In By the Sea (2011), Gurnah's previous novel, we see Zanzibari refugees fleeing to England; one of the characters refuses to speak in the language of the colonists as a sign of resistance. In each of Gurnah's novels, we find this sense of radical self-imagination and self-invention of the coloniser-oppressor and colonised-victim dynamic in nuanced portrayals, with exquisite attention to detail. Gurnah breathes into his writing a fiery incense in an effort to understand the "afterlives" of the colonial period, whose past can be felt by the needs of today's world. In many ways, we too are the afterlives of colonialism.

Israr Hasan is a research assistant at BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health.

For more book-related news and views, follow Daily Star Books on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Write to us at [email protected]. Read our coverage on American poet Louis Gluck, last year's Nobel laureate in literature.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments