Tanveer Anoy explores gender roles and identities in his second novel, ‘Duradhay’

Tanveer Anoy's second novel, Duradhay (Anandam, 2021), felt like a punch to my stomach; a wake up call, to be more precise. It seemed to offer wiper-blade clarity to all those subtle and stark nuances of uncertainty that a privileged, millennial, cisgender person like me could have a derivative idea of but would never truly fathom of their gravity. Am I qualified to write this review? I don't know if that is for me to decide, but I feel the need to mention that I could only have written this article from the perspective of an ally, as someone who wants to know, learn, and expand their understanding of people and society as a whole, without accommodating or unknowingly adhering to the lines that determine or discriminate.

The meaning of 'duradhay', the narrator-protagonist mentions, is something one cannot study or assess—it's the only word they have truly ever resonated with. Sixteen-year-old Tonim struggles with the reality of being born as a boy, in a family that struggles to understand why "he" dresses up like a girl and calls himself Tonima. The story opens with Tonim having attempted to take their own life, being rushed to the hospital, and being blamed by their financially struggling family for wasting money on hospital bills. Eventually, as school friends mock and abuse Tonim, and as parents demand an explanation for this "drama", Tonim reveals, through stream-of-consciousness monologues, that they feel more like a girl.

For us Bangla speakers, pronouns are figures of speech that we learn fleetingly in school; their application seldom goes beyond ticking a box on official documents and emails. Ironically, it is because Bangla has no distinctive gendered pronouns that I found it so overwhelming to explore, in limited words, the massive significance of Tonim having dual identities.

But Tonim's struggles throughout the book go beyond issues of gendered pronouns, and they are two-fold: the young protagonist deals with the characteristic troubles of adolescence, like being misunderstood by family, being bullied at school, and confronting innocent, often conflicting teenage emotions; on the other hand, their predicaments are more complex and up against formidable foes: centuries of antiquated, unforgiving and conformist social norms. Tonim is sent to a militantly religious "rehab" to get "fixed", from which they are rescued only to be sexually abused by their saviour. Running away from these very visceral dangers, Tonim vacillates between remaining the "effeminate" boy that everyone demands they are, and embracing their alter, Tonima, in whose persona they feel more at home.

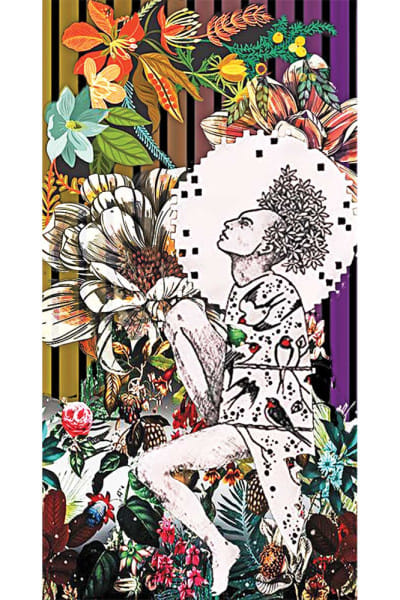

Truth be told, the beautiful cover art was what first drew me to this book. Artist Ankur Sinha does an excellent job in portraying the rich and complex world of a discovering teenager—a person perched, ornamented with flowers and birds—seemingly all awaiting to be explored.

The story, too, works as an extension of this elaborate microcosm in representing the protagonist's internal world. The author paces the succession of events leading up to their culmination in a way that makes sense in a short novel; the brevity allows the reader to internalise its full effect. And although the contents of the story are distressing, the quietude of their tone ascertains a softer blow to those watching.

Fair warning for the reader, though: this novel deals with graphic details of suicide, rape, and physical and psychological abuse; on various occasions, I needed to put the book down and grapple with the impact of what I had just read. But the purpose of these details transcends their need to flesh out a character. They will pull you down from the cloud of blissful ignorance and shake you into seeing the reality of an insular society.

The one thing that hindered the story from reaching its full potential, in my opinion, was the language. Tonim's vocabulary is quite complex, enough to be unconvincing as coming from a 10th grader, especially when you compare it with the simple, almost pedestrian language of his parents and peers. There is no clear reason given as to what would constitute this almost academic diction apart from a few fleeting references that the protagonist likes to read. Perhaps the writer tried to use language as a foil, to make Tonim's character seem more complex and thoughtful compared to others. But while the author uses stream-of-consciousness to great effect in reflecting Tonim's mind, their choice of words in Tonim's speech feels jarring. This becomes especially complicated in context of the seriousness of the themes explored in the book—we want this narrator to feel real and reliable, and the language seems to take away from this achievement. Some events in the plot, similarly, needed more expounding. The shift from Tonim's narration in the past to the present feels quite abrupt and leaves the reader asking for more context. These minor factors notwithstanding, Tonim's world as portrayed in the novel is powerful, vibrant, and telling.

Reading Duradhay, I realised that Tanveer Anoy's activism, and the vocalisation of issues including identity crises, assigned gender roles, sexual abuse, and trauma, has given floor to some potentially defining discourse for our community. This can lead to some difficult but necessary conversations in homes that are as indifferent and as severe as Tonim's. We see similar narratives play out in countless Western YA novels, but how often do we see them in conservative, sweep-things-under-the-rug South Asian cultures?

I get asked a lot why I decided to come back to Bangladesh after I spent all that time abroad. The only answer that I have is that I see this country on the brink of a revolution. It has been buzzing with the noise of an ushering change, and I didn't want to miss it when it happened. For me, Duradhay is a testament to that burgeoning change.

Maisha Syeda is a writer, painter, and a graduate of English Literature and Writing. She is an intern at Daily Star Books.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments