Think twice before giving in to fast fashion

The character of Miranda Priestly (played by Meryl Streep, from the 2006 film "The Devil Wears Prada"—albeit exaggerated for dramatic effect—was the boss of all our nightmares. But her iconic monologue about how fashion trends from the runways become diluted and eventually seep into our dull, regular lives cannot be faulted. But that was 15 years ago, and now, fashion trends are as accessible for the Andy Sachs' (portrayed by Anne Hathaway) of the world as can be.

Since the beginning of this millennium, trend cycles have been getting shorter and shorter, thanks to fast fashion producers such as Forever 21, Zara, and H&M. This has been allowed to go on to such an extent that now, over two decades later, fast fashion brands are putting out a new collection almost every week, each collection consisting of tens of new styles. This is further perpetuated with the rise of fashion influencers on the internet. Before, it was only celebrities whose style would dictate what was "in" at a given moment in time. Now, there are niche internet "micro-celebrities" in seemingly every neighbourhood of the world, who are able to influence fashion trends by flaunting their styles on platforms such as Instagram and TikTok. And though it is unclear which came first—influencer culture or fast fashion—there is no denying the fact that they both result in the production and dumping of tens of millions of clothes every year.

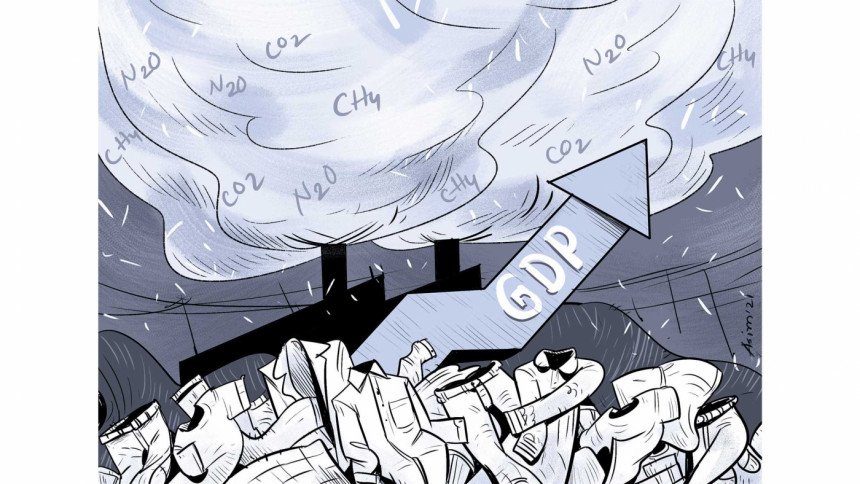

But the pollution that is caused by fashion is much more nuanced than trucks full of clothes being discarded into a landfill.

While high-end fashion companies moved from bringing out two collections per year to five in the last two decades, other, more retail-based brands offer tens of collections annually. Obviously, this has created demand and also fulfils it, but research suggests that people are also getting rid of clothes faster than they used to.

Data from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) shows that the fashion industry by itself is responsible for 10 percent of the world's carbon emission. If fast fashion is not stopped in its tracks, the emission could spike to 26 percent by 2050, according to estimates by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a UK-based charity that promotes circular economy. Meanwhile, even the washing of polyester clothes (a material found in about 60 percent of all fabrics) releases microplastics into our oceans, which never break down. In fact, a 2017 report by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimated that 35 percent of all microplastics found in the ocean came from the washing of synthetic clothes.

But the production of cotton clothes is no more innocent on the pollution front. Cotton itself is a very water-intensive plant, and to harvest and use it to make even one shirt and a pair of jeans could use up more than 12,200 litres of water, as per the data from UNEP and the World Resources Institute (WRI).

Such horrifying statistics should mean that all of us would be desperate to try and slow down the production of new clothes—if not eliminate it completely and use up what we already have. If only it were that simple.

Last year, locked in at home and resorting to retail therapy as the perfect distraction from the impending doom, I myself was in the thick of buying things online and being quite mindless about it. There was no forethought put into why I was buying what I was buying. Things would just come up on my social media feed through advertisements or from pages I already followed, and I would place an order simply because something seemed pretty or cool, and not because I felt a need to add it to my collection. But I would not stop at calling my purchases from that period "want-based" either. It was sheer impulse that I acted on, much stronger than need or want. And this kind of a "have to have it" approach to consumption, enabled by uber fast deliveries of products even from the other end of the world, is what allows fast fashion to grow and thrive—no matter one's knowledge and consciousness of the climate crisis.

All companies and many consumers in RMG-importing countries are aware of the environmental impacts of fast fashion, and there are often initiatives from both groups to be more "sustainable." Consumers may try to limit their purchases of new clothes and opt for thrift and charity stores, which help to keep clothes from ending up in landfills and also benefit a local community. Clothing retailers may only buy from factories which have certain green credentials, such as the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certificate. According to a Prothom Alo report, these "greener" RMG factories, of which there are about 135 in Bangladesh, can reduce electricity consumption by 24-50 percent, water consumption by 40 percent, and carbon emissions by 33-39 percent.

However, all that still does not change the truth that "sustainable fast fashion" is a paradox, no matter how many people consume said fashion responsibly and consciously. As long as trend cycles are getting shorter—and are being enabled by competitive production of clothes and widespread promotion of styles through social media—more clothes will be purchased and will subsequently be dumped, to stay in our environment and harm its creatures for thousands of years.

The dilemma for Bangladesh in this regard is a considerable one. Do we choose job creation and our economy, or do we save the environment? The obvious solution is the diversification of our export basket, so that the burden is taken off of RMG manufacturers to keep our economy growing. With 84 percent of our exports dependent on the RMG sector alone, this solution—if it ever occurs—will doubtlessly be an arduous one for us to reach. But more importantly, it will leave many of the estimated 4.2 million workers (as per a 2020 survey by the Asian Center for Development) of this sector jobless. When these factors are taken into account, it may seem that the eradication of fast fashion production will only harm Bangladesh.

But this is why it is important for us to take the beaten and battered phrase "whole-of-society approach" seriously when dealing with the climate crisis. Unlike the capitalist model of the textile and fashion industries, climate change does not discriminate between borders. Its effects will eventually get to all of us, unless we all—individuals, companies, intergovernmental organisations, and governments—do our part to curb them. Disaster is not imminent yet, but we must not allow it to become so.

To look out for our own, so to speak, the government must first create opportunities for our workers to develop their skills in areas besides RMG manufacturing. This, along with shifting the burden of our exports away from the same industry, could help Bangladesh be less of a participant in the using up and damaging of finite resources, the slow killing of wildlife and marine creatures, and the increasing of its own vulnerability to climate change. As consumers, we can act by making conscious choices instead of impulsive ones.

Instead of throwing away whatever you don't need, try to hoard your clothes. Even if an article does not "spark joy" now, it may do so in a few months or years. Or you can find someone—a friend, relative, acquaintance—to pass it down to, who you know will make good use of it. Even if one person's goodwill helps the environment in a minuscule way, it will have positive visible effects in one's own life in terms of less expenditure and clutter.

Consciously doing things to look after the environment is part of good housekeeping, and not limited to your immediate surroundings. Just because textile, fashion and other polluting industries turn a blind eye to their own misdoings—enabled by less climate vulnerable governments—does not mean consumers should too.

Afia Jahin is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments