Let’s give a new meaning to ‘Made in Bangladesh’

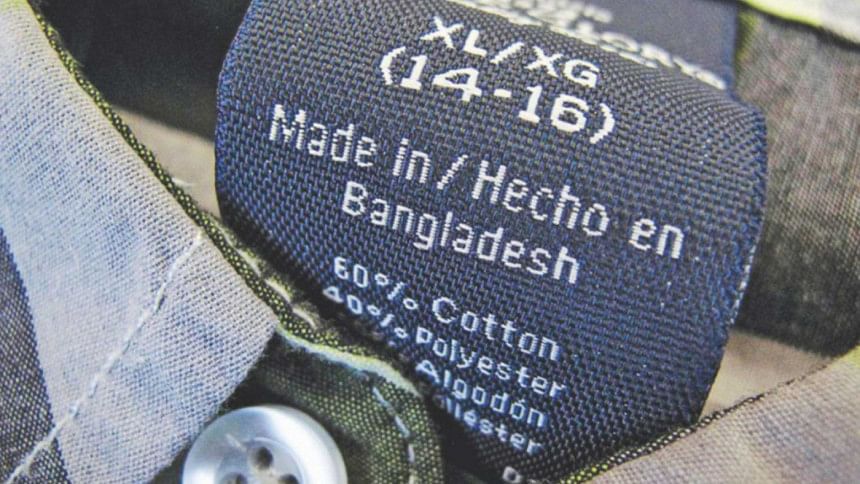

"Made in Bangladesh" is a brand which now resonates around the world, thanks to the size and global reach of our RMG industry. But what does it mean to end consumers? How does it resonate with the people who wear the clothing that garment workers toil to produce in our factories?

Having had the good fortune to travel a great deal these past two decades, I can say that our country's branding can offer mixed messages. For many Western consumers, it is associated with cheap clothing and a business model which sees Europe, the US and other Western countries outsource low-cost industries to the Global South. "Made in Bangladesh" has also developed some unsavoury connotations since the Rana Plaza collapse. The image of garment workers being crammed into unsafe factories—which no longer holds true for Bangladesh and needs to be stated—is one which has been hard to erase from a marketing and PR standpoint.

"Made in Bangladesh," then, offers mixed messages around the world. It does not have the standing of, say, "Made in Germany" or even "Made in England," but, it is a brand on the world stage—for good or bad.

How can we improve it, then? Telling people about the provenance and authenticity of the products they purchase is becoming an increasingly powerful marketing tool in a crowded global market. With so many products fighting for audience and market share, and so much social media noise, gaining cut through and creating a memorable impression with one's audience is a huge challenge.

I believe there are opportunities for the RMG industry of Bangladesh here. There is a growing interest in where and how products are made among consumers, and it is up to us, as the world's second largest producer of clothing, to respond to these new market dynamics.

Technology can play a key role here. In the textile and fashion space, we are increasingly seeing technology being used to track and trace textile fibres and garments from one part of the world to another, with blockchain also being used along the way. These generally see a unique "marker" being applied to textile fibres so that it then becomes possible to identify them along supply chains. Technological solutions like this are increasingly being demanded by our buyers in order to satisfy the requirements around supply chain transparency. This kind of technology is certainly the next big thing in our industry, and it is important that we, as suppliers, understand it and realise how it can be utilised.

Taking one recent example from another country: a traceable textile specialist has just announced a partnership with an industrial park developer in Africa to supply fully traceable cotton from Benin. This new pilot programme will enable spinner-to-garment traceability on products, offering huge potential to grow and develop Africa's cotton sector.

How we can make this kind of technology work in Bangladesh is something I believe our business and trade leaders need to look into now. I know that, just recently, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) made announcements around an increased focus on recycled products. As I have written previously, fashion is already asking supply chains how they can help boost recycled products in their collections, and a number of buyers are working with Bangladesh in this area. Suppliers in Bangladesh need to be looking at how they can forge links with textile recyclers.

But perhaps we can combine the two? One of the challenges for garments containing recycled materials is that it is not always possible to be 100 percent sure whether the materials in the garment are what is claimed. It could be recycled content, but there have been stories in the news lately that virgin fibres are being used in their place. This is one area where traceability solutions could come to the fore, and there is no reason why Bangladesh should not help lead the way. Could Bangladeshi apparel makers team up with recycling partners and traceable tech companies to provide fully traceable garments, where it is possible to provide, via a barcode on the end product, the precise content of the clothing? This is the futuristic direction our industry is heading to.

Bringing this kind of added value to end clothing products gives a whole new meaning to the term "Made in Bangladesh." It is a brilliant way to help us on our rebranding journey, shifting away from a country which simply produces staple clothing items to one which creates clothing that is made using recycled fibres, is fully traceable and can demonstrate the kind of authentic sustainability values that brands and their end consumers are looking for these days.

At present, there are all manners of recycling projects globally seeking business partners. Likewise, in the traceable fibres space, there are small but a growing band of companies offering end-to-end traceability solutions. Our suppliers and, at a broader, more strategic level, our industry leaders and even the government authorities need to be making connections with these companies to see where synergies can be developed. Our buyers also need to be in on these conversations.

Our industry is changing—and at a faster rate than one could imagine. If we don't embrace these new technologies, we will be left behind. So, let's get behind them and use them to our advantage, as a way to add value to what we do and freshen up the "Made in Bangladesh" brand, giving it extra dimension and meaning in our increasingly interconnected global market.

Mostafiz Uddin is the managing director of Denim Expert Limited, and the founder and CEO of Bangladesh Apparel Exchange (BAE) and Bangladesh Denim Expo.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments